Ten years ago, Matt Reeves’ secret monster movie ushered in a new era of fan-driven movie publicity.

There’s a post on Ain’t It Cool News from 9 July, 2007 entitled ‘JJ Abrams drops Harry a line on all this 1-18-08 stuff’. In 2018, it’s hard to imagine Abrams, who has since gone on to successfully reboot not one but two of the biggest franchises in movie history, sending a cordial and casual message direct to the inbox of former fanboy-in-chief and now publicly outed abuser Harry Knowles. Needless to say, quite a bit has changed in the past decade.

2007 was the dawn of a new era, both for movies and online journalism. Reading them now, blog posts and pop culture news sites from that age speak to a simpler – or at least different – time, when Abrams was attached to The Dark Tower and not to Star Wars, Ain’t It Cool News was the predominant voice in fanboy journalism, and Disney had yet to cement their ever-growing monopoly over the mainstream movie market. There were no post-credits scenes, blockbusters rarely broke over a billion dollars at the box office, and the type of hyper-analysis and GIF-ification that happens online anytime a trailer drops was only for the hardcore fans. Though superheroes had been Hollywood’s genre du jour for almost a decade, Iron Man, Marvel’s new crown jewel, was just a speck on the horizon, a deeper cut unfamiliar to almost anyone but the truest of believers until May 2008.

But in the middle of the summer of 2007, a movie season dominated by the third entries in the Spider-Man, Shrek, and Pirates of the Caribbean franchises, a bomb dropped: the trailer for Abrams and Matt Reeves’ Cloverfield, attached to the first Transformers on its opening weekend. The preview, for a film then completely unknown to the general public, begins with camcorder footage of young New Yorkers in the middle of a going-away party for a friend. About 30 seconds in, the lights go out. Loud rumbles are heard. A fireball streaks through the sky. Someone yells, “It’s alive!” The trailer closes with a now iconic image: Lady Liberty’s decapitated head smashing into the streets of Manhattan. The entire spectacle, perhaps unconsciously in 2008 and more obviously with hindsight, instantly evokes 9/11.

This stunt, to release a trailer for a secretly-produced film into theatres without a title even attached to it, was as fresh as newly-skinned knee. For many movie fans, the ensuing months disappeared down a rabbit hole of clues, rumours and red herrings about the film known at that time simply by its release date: 1-18-08. Speculation ran rampant on the various message boards, Blogspots and LiveJournal pages devoted to the film; some said it was a new American Godzilla, others a big-screen Voltron adaptation or Cthulhu movie. The Bad Robot logo and the trailer’s opening led many to speculate that Lost was hitting the big screen. Bloody Disgusting reported that the project was entitled Monstrous, some suggested it would be called Colossal or Slusho. But the real title was there all along: Cloverfield, as reported by Ain’t It Cool News on 21 June, 2007.

Comparisons to The Blair Witch Project, which had executed a not dissimilar campaign almost a decade earlier, inevitably arose in discussion of this new Abrams project. Despite the cultural firestorm it caused, The Blair Witch Project was an isolated incident, with few mainstream films afterward attempting to replicate its success, and even fewer achieving anything close to the sensation that was Blair Witch. Though that film’s sequel, directed by established documentarian Joe Berlinger, laid the metatextuality on thick, it abandoned its predecessor’s central formal gimmick. Most found footage films afterward were relegated to the direct-to-video dustbin. But the one-two punch of Cloverfield and Paranormal Activity (produced in 2007 but released in 2009) proved that the subgenre had staying power, and would soon expand outside of horror with the likes of Chronicle and Project X.

Even though Cloverfield opened the floodgates for found footage, it’s not in this arena that the film has been most influential. Rather, Cloverfield ushered in the current era of pre-release publicity and hype marketing. Around the mid-to-late 2000s, viral marketing campaigns were all the rage, with everything from The Dark Knight to The Da Vinci Code arriving pre-packaged with an augmented reality game (ARG). In 2018, that term is most closely associated with mobile games like Pokemon Go, but for the purposes of movie marketing ARGs functioned as promotional scavenger hunts, prompting dedicated fans to scour the web for clues pertaining to a new piece of media. Abrams himself dabbled in ARGs with his hit TV shows Alias and Lost.

According to film theorist Dan North, “Traditional publicity campaigns rely on the carefully timed release of authoritative information from a central source to a mass audience. Viral campaigns, in contrast, depend on relinquishing control: releasing key pieces of information in carefully chosen places, in the hope and expectation that it will spread organically through the target audience, as a virus spreads from person to person.” The “release of authoritative information” could still describe most marketing campaigns: studios carefully time the release of a series of teasers and trailers, each revealing more information than the last, in order to drum up the desired interest from audiences.

Sometimes, in the case of a film like Star Wars: The Force Awakens, trailers withhold plot details in favour of a few select images, which leads to intense online speculation about the movie’s storyline, potential new characters, and the inclusion of old favourites. But too often the internet bemoans formulaic or spoilerific trailers, or those which advertise a different movie than is received (in the case of Suicide Squad, the film itself was re-edited to more closely resemble the rhythm of its well-received trailer).

In sharp contrast, the publicity teams at Paramount and Bad Robot mounted a marketing campaign for Cloverfield that, instead of explicitly stating what the film would be, allowed viewers to participate firsthand in the unfolding publicity circus. Information released prior to the film’s premiere could best be described as breadcrumbs: the trailer, shot before the film was completed and containing obscured images which generated ravenous speculation; the website, 1-18-08.com, filled with time-coded photos correlating to the trailer; and a handful of seemingly random clues scattered across the internet. Among these hints were websites for Slusho, a fictional soft drink brand which has become a recurring an Easter egg in Abrams’ filmography, and Tagurato, a non-existent Japanese company somehow involvement in the unearthing of the Cloverfield monster.

Part of the difficulty in writing about a viral marketing campaign that took place a decade ago is that many of its most vital pieces no longer exist – 1-18-08.com now redirects to the Paramount website, while cloverfieldmovie.com takes you to the film’s official Facebook page. Shortly after the release of Cloverfield, a hotline number which once provided a ringtone of the monster’s roar began serving updates on upcoming Paramount releases such as The Love Guru and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

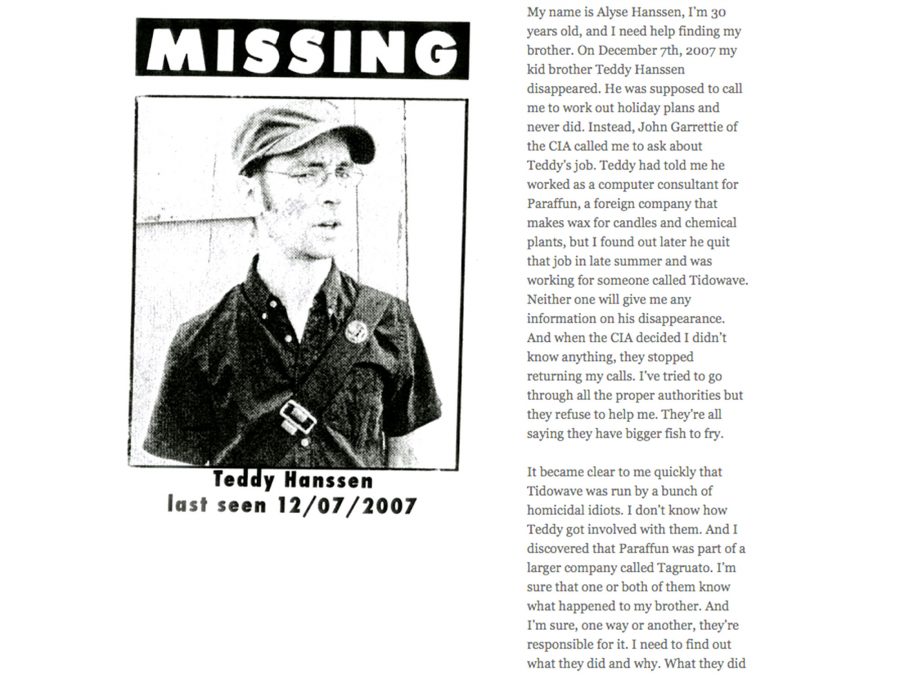

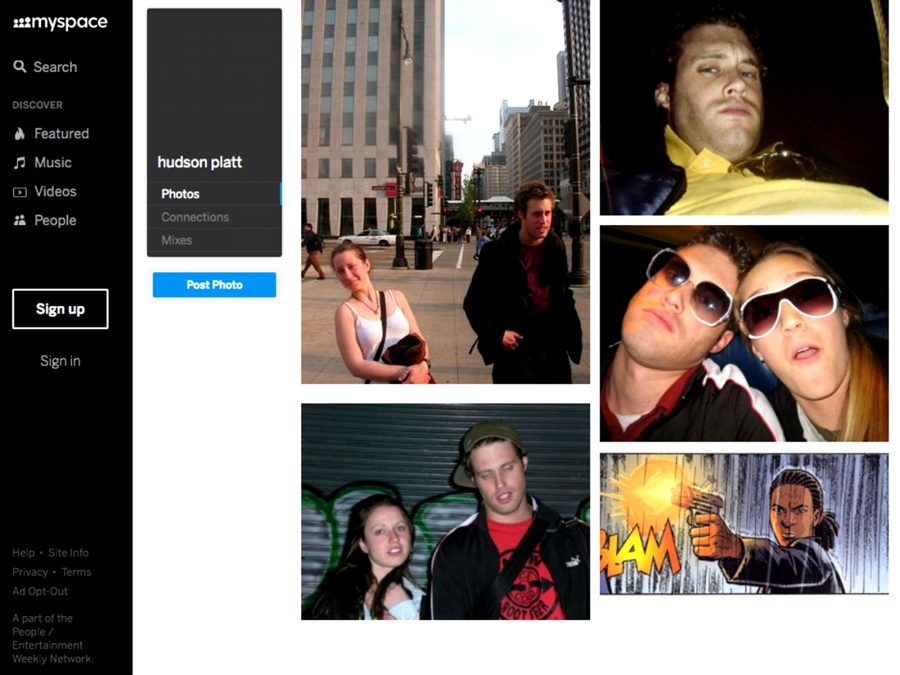

Another website, usgx8810b467233px.com, which contained images of and documents about an oil drill by Tagurato, has also been taken offline. Several sites related to the film’s characters are still active, however, including a private blog called Jamie and Teddy (which can be accessed with the password jllovesth); Missing Teddy Hansen, a Blogspot page about a man who has gone missing in the attacks; tidowave.wave, a blog devoted to detailing the environmentally harmful exploits of Tagurato; as well as MySpace pages for all the main characters (though specific posts from those pages have been removed).

In a post-Emoji Movie world, it’s a little strange looking at a MySpace page for “Hudson Platt”, the character played by TJ Miller in Cloverfield (it bears mentioning that Miller, like Knowles, is another figure attached to this saga with a now-public laundry list of assault and harassment allegations). It leads one to wonder how long these surviving sites will remain online. Perhaps in the distant future such promotional pages will be stumbled upon by online archaeologists, with no memory of their connection to the film, and be taken as artifacts of real people.

Cyberspace is a fickle mistress, and that is part of the danger – and appeal – of viral marketing campaigns. During the hunt for Cloverfield clues, many speculated that another website, ethanhaaswasright.com, bore some connection to the film. But Abrams dispelled those rumours in a letter to Ain’t It Cool News, and the site turned out to be part of a separate ARG for Mind Storm Labs’ role-playing game Alpha Omega: The Beginning and The End. But even red herrings like Ethan Haas only worked to the benefit of the Cloverfield publicity campaign: even though it had nothing to do with the film, it kept the conversation going.

Viral marketing campaigns, then, are less about the specifics of the marketing conversation then they are about the conversation itself. The genesis of hype is left not to publicists or press teams, but to fans themselves, who become responsible for the construction of public interest in a film. Cloverfield engaged directly with fans in another way. As Catherine Zimmer notes in her book ‘Surveillance Cinema’, Paramount created a contest in which fans were encouraged to produce videos “imagining their own Cloverfield-esque response to a monster attack as captured on their consumer electronic equipment.” Fans then voted for their favourite video, which gave further attention to the film with minimal effort exerted on the part of Paramount.

The Australian notes in a January 2008 article about “cloak-and-dagger” promotional techniques that perhaps, “The best way to market a product to a young and wired generation is not to market it all.” Though the marketing for Cloverfield can certainly be deemed as such, it wasn’t Paramount who were doing the heavy lifting. Theorist Emmanuelle Wessels notes that, “Although participants in the Cloverfield vote do, presumably, enjoy the affective pleasures of agency in selecting their favourite video, they also labor to consume advertising and promotion for Paramount, and supply an email address likely to ensure future monitoring and advertising reception.” With such contests, as well as the strategic deployment of piecemeal clues, Paramount effectively outsourced their marketing and publicity work to fans. Participants in the ARG then had a vested interest in going to see the movie: to find out if their pet theories made it into the finished product, or if even more clues emerged.

But as many found out 10 years ago on 18 January, 2008, few if any of the details in the campaign and its corresponding game played an important role in the actual film. As director Matt Reeves said of the marketing campaign, “You could call it – a sort of ‘meta-story’ that is part of – almost like an origin story – that is connected. It’s almost like tentacles that grow out of the film and lead, also, to the ideas in the film. And there’s this weird way where you can go see the movie and it’s one experience. It’s a big, really satisfying and really thrilling experience.” The Cloverfield campaign developed a hardcore contingency of loyal Cloverfield fans who had participated in the ARG and were then almost ensured to see the movie upon release. But the experience of the film wasn’t hindered for those who didn’t know about the pre-release ARG.

Abrams developed ARGs and viral marketing campaigns for his subsequent films, including Super 8 and 10 Cloverfield Lane, the Dan Trachtenberg directed spin-off, the trailer for which dropped Beyoncé-style before another Michael Bay film, 2016’s 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi. Though many fans who participated in the original Cloverfield ARG have gone on to play the later games, the internet has largely ignored them. Even then, interest in Cloverfield has continued, and upcoming sequels God Particle (originally scheduled for release this February but now delayed until April) and Overlord are speculated to keep the Cloververse alive.

So, if few films have replicated the exact success of Cloverfield’s viral marketing campaign, how exactly has it influenced modern movie publicity? Even if the film’s influence has only been indirect, it set an important precedent. Scour any number of blogs devoted to the collection of clues about Cloverfield, which bear outdated URLs like 1-18-08.blogspot.com and 1-18-08.livejournal.com, and you’ll find the work of fans with a little too much time on their hands. Many argued over whether an off-screen voice in the trailer yelled “It’s alive!” or “It’s a lion!” One devotee proclaims that we needn’t worry, he’s extracted the trailer’s audio into six separate tracks to uncover the truth (“It’s alive!”). Such hyper-analysis predicted today’s climate, in which every piece of marketing for the latest franchise instalment is subject to instant screen-grabbing and speculation. Even art-house fare like Todd Haynes’ Carol and Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name have had moments from their trailers transformed into GIFs.

The reporting leading up to Cloverfield also mirrors the way online film journalism often operates today. Sites like Latino Review have become notorious for publishing each and every rumour about high-profile releases. These scraps of information, however accurate, keep the clicks rolling in and the lights on, both at tabloid-y fan sites and studio publicity departments, who maintain an ouroboros of a relationship with one another. Due to limited leads on Cloverfield, even publications like USA Today couldn’t help but put out information, like the Ethan Haas herring, which turned out to be false. But that worked to the benefit of both the movie and those who covered it: interest in Cloverfield grew, and fans kept reading.

Although the success of Cloverfield’s viral campaign hasn’t been directly replicated, it awakened a marketing monster that continues to roar along. The many changes the internet has wrought on our consumption of and engagement with popular cinema are not owed entirely to Reeves’ film, but at the very least it is a valuable case study, and an early adopter of a system we’ve grown accustomed to. It’s alive, indeed.

Published 13 Jan 2018

Directors Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick tell the story of how their freshman film project became a cultural phenomenon.

This frisky and frenetic sort-of-sequel to Matt Reeves’ 2008 monster movie boasts a trio of amazing performances.

By Tom Bond

It’s become increasingly rare for films like Batman V Supeman: Dawn of Justice to live up to expectations.