The actor discusses the ambiguity of his role in Judas and the Black Messiah while espousing peace, love and connectivity.

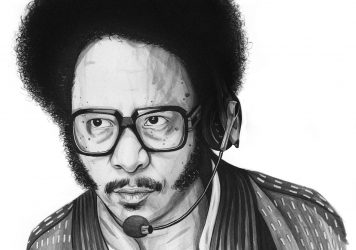

LaKeith Stanfield is a rare kind of movie star, as unique and enigmatic a presence off the screen as on. He possesses a striking authenticity that radiates through each one of wildly varied roles, from lackadaisical philosopher-poet Darius in TV series Atlanta, to the surreal telemarketer Cash in Boots Riley’s workplace satire Sorry to Bother You, to a victim of a racist body possession in Jordan Peele’s horror parable Get Out.

This year he reunites with his Get Out co-stars Daniel Kaluuya and Lil Rel Howery for Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah, playing William O’Neal, an FBI informant responsible for the assassination of prominent Black Panther Fred Hampton.

LWLies: You’re such a chameleon of an actor. What do you look for in a role?

Stanfield: It’s hard to say. What can people look for? I’d say keep your expectations open. I don’t really ever know what I’m going to do next or what might move me as I grow. I love to have fun – sometimes too much fun – but that might be a problem of mine. I love to tell stories that are deeply entrenched in emotional exploration.

You’ve worked with a lot of Black filmmakers on the projects that launched them to the next level: Ava DuVernay; Jordan Peele; Boots Riley; and now Shaka King. Are you particularly interested in working with up-and-coming filmmakers?

Absolutely. We all start somewhere and there’s a whole wealth of potential out in the world. Early on in my career, I got to work with very talented people who allowed me to join them on their journey. I’m really interested in new faces and bringing their unique style to the format. It’s important to believe in what you’re doing, and I think all of those people you mentioned, they believed in the story and they put all of their intention behind it. So that’s why you get the results you get.

When you were making Get Out did you have a sense that you were creating a classic?

Not at all! When you’re crafting a film, to have that kind of arrogance would be scary. There are just so many unknowns when it comes to making it about how it will be edited, how it will be received, where it will be received, if it’ll even ever come out, if we’re even going to finish making the movie – because movies are hard to make and they’re expensive. I just couldn’t imagine making a movie at any time thinking, ‘this is going to be great.’ We put our best foot forward and we worked with integrity and confidence, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone make a film that was worth watching who believed hallway through it was going to be the best, new, big thing.

A lot of people watching this film will be shocked by what the FBI did to the Black Panthers. Was it shocking for you to discover?

That’s what they did to everyone that tried to rise up. If you were an organisation that did things the way they didn’t see fit, they would infiltrate. Particularly ones that represented a sort of uprising, because they were insecure about the rise of a Black Messiah. But if your government is afraid of people collaborating and getting together, what might that indicate about them?

After the Confederate statues come down, they need to get rid of the J Edgar Hoover building. What he did to the Black community is despicable.

I don’t think that we should glorify and hold these people up with reverence. I take issue with idol worship in general, even with, like, celebrities and stuff. But especially these people that just check that record. They’re not good people! It’s irritating. I say get them off the money too.

Andrew Jackson is on the $20 and he literally committed genocide.

I am not a supporter of that type of idol worship, especially with politicians.

You are playing a character who’s lying all the time. How do you approach performing both the truth and the deception?

It was a unique challenge. I never had to do something before where I’m considering so many dimensions at once. So it kind of feels like everything’s going at an accelerated speed in the scenes. I mapped it out for a long time with the script in my head – how this would happen, what this reaction looks like. And then a lot of it was also just letting go in the moment and letting things happen. I had a whole plan, a whole map, and I kind of executed that plan. And then for the rest of it, I just was reacting as if I was trying to keep a secret. Yeah. I think it worked.

Did you feel a particular responsibility to change the perception of the Black Panthers?

Yeah. Stupid media, always lying and creating a fake version of what they fear about Black people in power. I think that’s really what it is. There’s a big fear about people of colour being in power. So they make all these fake versions and propaganda about who the Black Panthers were. They weren’t terrorists. They weren’t trying to burn down the city or the country. They were activists. They were revolutionaries.

They were people that saw a new way for us and actively put in action to see about making that change. Some of their programmes the government even co-opted. But they just couldn’t stand to see us rising in that way. So I just wanted to represent the Panthers. I always knew that Panthers weren’t what was largely represented, even though they don’t even really talk about them in school, which sucks. So I just wanted to represent them and any way I could be of service to that, I wanted to be.

“It’s my perception that we’re all having one big story together. We’re just experiencing it at different times.”

It must have been tough to play someone who worked to bring down the Panthers then?

It was hard to play William O’Neal because I care so much about the Panthers and their message. Sometimes I was really at odds with what he was doing and what the character was doing. But I guess that was part of what it meant to dive into this character. It meant me being in conflict a little internally. I came out the end of it with a profound understanding.

It’s hard to say I understand O’Neal and his relationship to the Panthers more now than I did before. I understand Fred now more in a way. I think that’s invaluable, you know? I know movies can’t do everything, but if we can help people learn about Fred Hampton, to learn about the Black Panthers, to learn about William O’Neal, who represents an integral idea of what it means to be human. What it means to betray. What it means to be afraid. These are important things. So I’m glad to help tell their story.

You have played real people in the past, Snoop in Straight Out of Compton and Jimmy Lee Jackson in Selma. Did you do a lot of research for those roles or just approach it – as with this – as a regular role, something that doesn’t necessarily need to be rooted in reality?

When you’re playing someone real, you want to try and do your due diligence – to have integrity with how you interpret them. Even if it’s someone like William O’Neal that you may be at odds with, you have to respect the humanity of the person at the end of the day. So I wanted to make sure that I am not making him seem like some spooky villain no one can relate to because I don’t think those types of people actually exist. There may be people who you really disagree with, but they’re still human. They still have a story. And it’s my perception that we’re all having one big story together. We’re just experiencing it at different times.

So if we can try and understand the other person’s perspective, then I think we can actually begin to have conversations. If we cast people out as just bad or just a villain then you can’t talk to them. I might be going a bit deep here, but that’s what I think about when it comes to stories and characters. I want to try and find the beauty in them. We all start off as babies and we’re just beautiful blank canvases and then the information we’re given builds us up into who we become. And we can’t forget that even if someone has become what seems like a monster to us, they were a baby at one point and that baby’s still inside.

I felt sorry for William O’Neal a lot of times, what the FBI was doing to him, putting him in these impossible situations but then you see the other side of the coin with Fred Hampton, who would rather sacrifice himself than betray everyone.

There were moments, for sure, where I think he felt he had no option and he had to go along with the game. Fear became stronger than love. The coin that you speak of is also the coin of fear and love, right? There’s a fine line between running and fighting. It’s really hard to quantify what the right decision to make in a situation like that would have been. Some people are terrified of jail and the prospect that they might not see their family and loved ones for years or be locked in a cage. The most insane punishment you can give a person is to put them in a cage.

So I did empathise with certain things. Although I found myself frustrated by some of his decisions. He got someone very important killed, someone that was fighting for him, fighting for his kind. It’s just a really challenging and conflicting story at the end of the day. It’s all tragic. Although I left the film feeling inspired by Fred’s story. I said, if he can do that, I should be doing more. When you’re at a crossroads now you might think about whether you want to take the O’Neal route or the Hampton route.

Was your performance informed by the actual Judas?

It’s an age old story, right? Jesus and Judas to me are representations of anthropomorphised spiritual things. Through the course of humanity, there always have been Jesuses and Judases. There’s a lot of essence and, yeah, these two people in this story represent archetypes. To all intents and purposes, O’Neal is Judas and Fred Hampton was Jesus.

Your scenes with Jesse Plemons where he’s talking about this false equivalence of the Black Panthers being as bad as the KKK, that could be on Fox News today and is a bit like Donald Trump saying “very fine people on both sides”. Did it feel modern?

Of course. Yeah, unfortunately not much has changed and I think a part of the reason why is because, like I was saying earlier, we’re not able to engage in honest discourse. I’m not able to really find you answers to these problems because people don’t speak, they just want to fight. A lot of these news channels are very biased and they stand on one side and it’s ‘fuck the other side’. It’s all divisiveness at the end of the day. Very rarely do we see people coming together on those public platforms and, like Fred was trying to do, with the Rainbow Coalition. We need people to come together and understand we all have the same fight. That’s why they wanted to stamp it out because division makes for better control. We have to find some bridge that brings us all together.

I’m glad that the film is coming out now; it’s going to make an impact. But at the same time I wish it wasn’t so relevant.

Yeah [sighs]. It is. I really love that it can help, if nothing else, drive the dialogue forward. That’s what we want to do. We just want to continue to have the discussions. I feel hopeful for humanity in spite of everything. I think that we survive and we push through and we’re best when we work together. I think films like this help reiterate that idea.

What is in the pipeline that we can look forward to?

I’ve got an anime coming out with Netflix called Yasuke, which I’m executive producing and starring in. I’ve got a movie called The Harder They Fall coming out, starring Idris Elba, Regina King, myself, Jonathan Majors and Zazie Beetz that is a Black western. My album is coming out soon – my debut rap album, my first musical attempt, which shall be fun and very funny, and very sad actually, too.

Published 12 Mar 2021

By Leila Latif

Commanding performances from LaKeith Stanfield and Daniel Kaluuya power this electrifying Black Panther drama.

Human resources’ worst nightmare talks about his surreal ode to collectivised action, Sorry to Bother You.

Like the era it represents, there are highs and lows in director Göran Hugo Olsson’s latest documentary.