Todd Haynes’ first documentary takes a thrilling, cautiously ambivalent look at the NY art-rock demigods.

With his films Velvet Goldmine and I’m Not There, director Todd Haynes has a strong claim to the title of our greatest feature film music critic. They are both not-quite-biopics, and each takes a sideways, yet pointed perspective on the legacies of two generation-defining icons: David Bowie and Bob Dylan.

Velvet Goldmine files the serial numbers off the glam era, changing names yet burning brightly with fury at how its stars eventually abandoned the Moonage Daydream. I’m Not There, meanwhile, viewed Dylan through a kaleidoscope, casting six actors to reveal a shapeshifter often at odds with himself and his art. Haynes’ latest is an excellent and expansive documentary – the director’s first – and is for once given a straightforward title that, on the face of it, appears to clearly pinpoint its subject: The Velvet Underground.

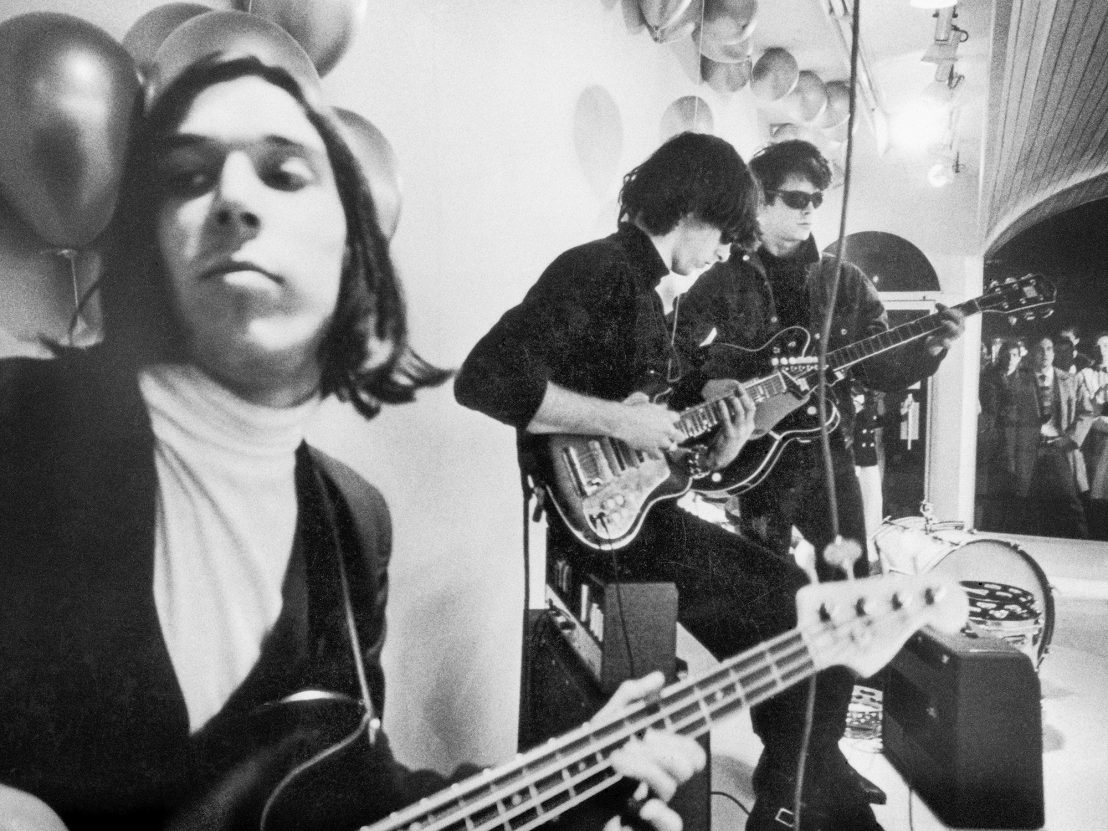

Perhaps the ultimate cult pop group, the Velvets combined rock ‘n’ roll with avant-garde influences to form a heady, dissonant sound that was distinctly their own, and completely out of step with the flower-power mainstream of the time. Packaged and presented to the world by pop-art maestro Andy Warhol as part of his Factory empire, the band recorded four albums in four years before effectively splitting in 1970. Their lead songwriter Lou Reed would rise to prominence as a solo act later in the decade, while the band’s small body of work would eventually inspire many other artists from David Bowie to Talking Heads to Joy Division to The Strokes.

Inspiration; breakthrough; commercial failure; revival. The story of the Velvet Underground naturally lends itself to a cradle-to-grave-to-resurrection narrative, but Haynes follows his own personal path. Formally, there’s an edgy rejection of the expected mixture of talking heads and archive footage (although, of course, there’s plenty of both in the mix). Haynes favours split-screens, frames within frames, and off-centre compositions to create compelling visual juxtapositions, the first being a compare/contrast introduction to the band’s two driving creative forces: songwriter-guitarist Reed and multi-instrumentalist John Cale.

We first see Cale in archive footage, wheeled out as a contestant on the game show I’ve Got a Secret – that secret being that he has just contributed to an 18 hour-long performance of Erik Satie’s marathon minimalist piano work Vexations. A prodigy from a Welsh mining village, Cale couldn’t be further removed in background from Reed, the Long Island-born son of an accountant brought up on television, doo wop and Bo Diddley, who later found work as a songwriter cranking out knock-off pop tunes for the budget label Pickwick Records.

Cale and Reed’s paths cross in New York, at the epicentre of a burgeoning art scene, and it’s here where Haynes diverges most from the pop-doc rulebook. Sure, there are the backstage anecdotes, the archive footage, the demo recordings and sequences set to the electrifying studio versions of ‘Heroin’, ‘Venus in Furs’ and ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’, but Haynes asserts that the Velvet Underground were a product of – and offer listeners a gateway into – a universe of radical art, from the filmmaking of Jonas Mekas and The Film-Makers’ Cooperative, to beat poetry, to Lamont Young and Tony Conrad’s experiments with drone music, to Andy Warhol’s prolific multimedia output. The video archive materials in this film, which include several of Warhol’s entrancing living-portrait ‘Screen Tests’, are worth the price of admission alone.

This might explain why Haynes’s interest wavers ever so slightly as it progresses through the band’s story, as first Warhol and then Cale are kicked to the curb and Reed pursues a more cohesive, commercial sound. The innocuous line in the opening verse of joyous pop-stomper ‘Sweet Jane’, “Me, I’m in a rock and roll band”, has never sounded so sinister. Throughout, Reed retains a certain mystique: he is described as ‘gay adjacent’, while it is also said that he lived a certain life in order to mine those experiences and encounters for his lyrics, and that most of all, more than anything, he wanted to be a rock star.

As with both Velvet Goldmine and I’m Not There, Haynes finds an enthralling middle ground between hero worship and ambivalence. There’s no thrill, no intrigue in hagiography. It’s the music, and where it takes you, what it opens up for you, that’s the thing. Haynes understands this, and so it’s no accident that he starts this unconventional, yet revelatory documentary about an unconventional, yet revelatory band with a quote from Baudelaire: “Music fathoms the sky”.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them. But to keep going, and growing, we need your support. Become a member today.

Published 11 Jul 2021

The director’s third feature from 1998 is a glitter-covered ode to the 1970s.

From Brief Encounter to his upcoming Peggy Lee biopic, the Carol director muses on a variety of subjects.