André Holland plays a sports agent who takes on the NBA in this quietly radical drama from Steven Soderbergh.

Despite its vertiginous title, Steven Soderbergh’s first feature of 2019 primarily concerns the fetid underbelly of an American institution and, to a certain extent, society as a whole. While the hoop dreams of ghettoised African-American males have long made for rich and compelling narrative drama, High Flying Bird tackles this subject side-on, offering a glimpse into the murkier, transactional side of professional basketball.

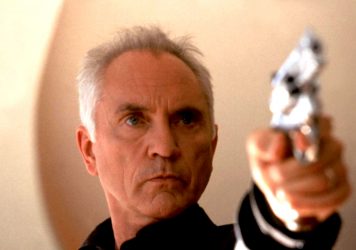

The film has been favourably compared to Bennett Miller’s Moneyball – which Soderbergh himself intended to direct back in 2009 before creative differences set him on a different path – though it is more overtly political and spiritual than that. Quite unconventionally, this is a sports movie in which a ball is hardly bounced, the action taking place almost entirely out of public view and, Kyle MacLachlan’s sauna ambush aside, without a drop of sweat in sight.

Ray Burke (André Holland, a revelation in Soderbergh’s The Knick and again here) is an articulate and savvy New York sports agent caught in the middle of a “lockout” which has brought the NBA season to a standstill. This not only tests Burke’s relationship with assistant Sam (Zazie Beetz) and VIP client Erick (Melvin Gregg) but also threatens his livelihood and everything he has worked for. Over the course of 72 hours we watch him attempt to break the impasse while slyly tipping the scales in his favour.

As Burke sets about manipulating and outmanoeuvring rival agents, NBA reps and even his own boss (Zachary Quinto), we get a sense of his intimate knowledge of the business of basketball as well as his passion for the game and those who play it. In private conversations with Scott, he talks about wanting to give athletes more agency and encourages the promising rookie to stop thinking small and start dreaming big. More pointedly, while shooting baskets and the breeze with his mentor, a veteran youth coach named Spence (Bill Duke in his most rewarding role in years), Burke rails against the rampant exploitation and commoditisation of black bodies.

Both men lament the control white administrators and network executives exert over the league’s most valuable assets (“They invented a game on top of a game,” as Spence eloquently puts it). But what are they to do about it? Burke’s answer is an ingenious one. As someone who understands the value of image ownership in the information era, he hatches a scheme to undermine the NBA by presenting a thoroughly modern alternate to its existing product. Given Soderbergh’s DIY ethos and reputation as something of a maverick, the audacious, anarchic manner in which Burke executes his game-winning play feels doubly significant.

The irony, of course, is that Burke too profits off these young men, leveraging their talent, ambition and inexperience for his own financial gain (to that end, Jeryl Prescott’s mother/agent would perhaps have made for an even more fascinating protagonist). Crucially, however, Soderbergh and screenwriter Tarell Alvin McCraney, who previously wrote the script for Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, show Burke to be a man of moral and ethical integrity who is simply taking advantage of an unfortunate situation.

High Flying Bird was filmed on an iPhone 8 fitted with an anamorphic lens, Soderbergh once again acting as his own DoP under the alias Peter Andrews. Where he utilised a similar technique to disorienting, conspicuously lo-fi effect in 2018’s Unsane, here fluid, tripod-mounted long takes establish a sleeker look and rhythm. As Burke dashes between high-rise office blocks and restaurants to conduct his surreptitious dealings, Soderbergh’s roving, wide-angle camera emphasises the imposing structures which dominate this corporate environment, while also underlining the metaphorical heights Burke – and by extension all black men – must scale in order to achieve parity, let alone greater influence and autonomy, in white America.

McCraney deserves huge credit for eschewing cheap sentimentality and hard-worn cynicism, which might have rendered this tale of greed, faith and power as merely Moneyball-lite. But it is the radical methods and perspective Soderbergh employs that make this feel like an urgent and incisive examination of the intersection between race, sport and money in America today. The revolution may not be televised, but you can bet it’ll be shot on a smartphone.

Published 7 Feb 2019

Steven Soderbergh only makes bangers.

Understated brilliance. So much going on in its 90-minute runtime.

Another Soderbergh slam dunk.

This late ’90s neo-noir offers a heady mix of non-linear narratives, cockney rhyming slang, and Terence Stamp.

By Matt Thrift

The American director discusses his long-awaited return to feature filmmaking with Logan Lucky.

Netflix’s college football documentary series offers a fascinating look at the business of sport and academia.