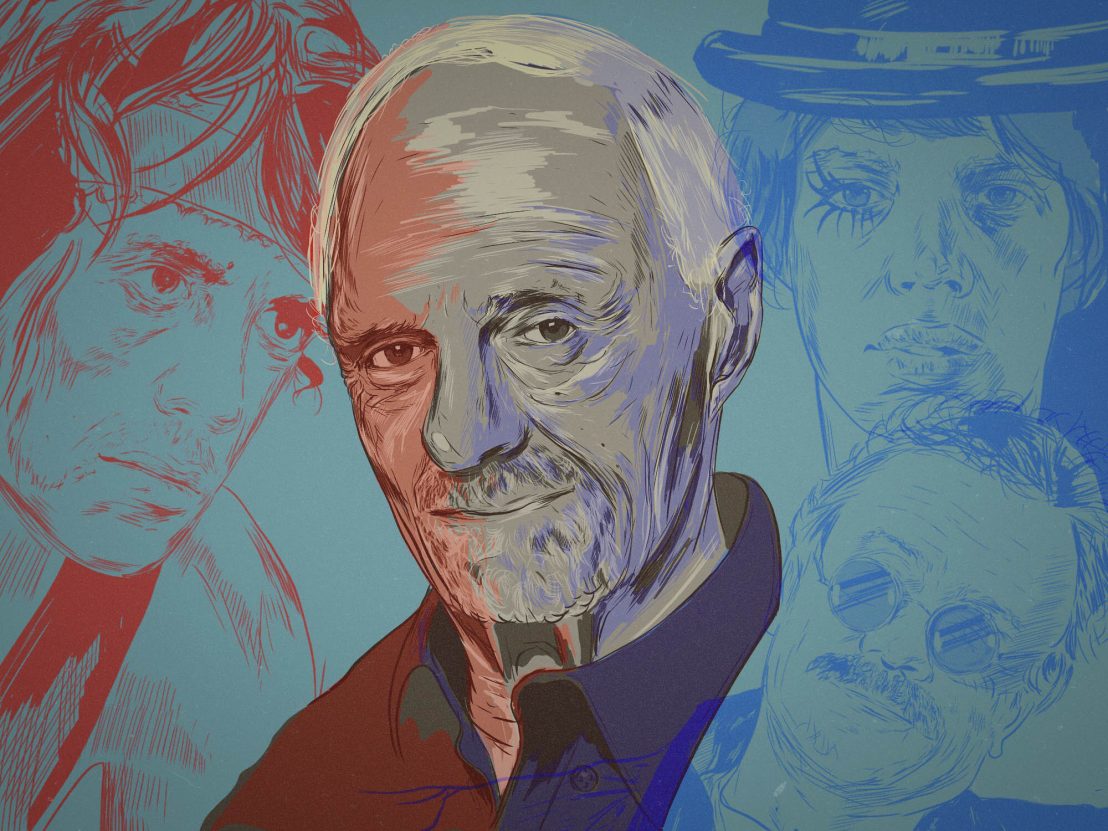

The veteran director of First Blood and Weekend at Bernie’s reflects on his remarkably varied career.

Toronto-born director and producer Ted Kotcheff doesn’t comply with any critical ideals of auteurism, and his name isn’t familiar even to those who have enjoyed his output over the last 50 years. Kotcheff has moved between genre (comedy, action, western, drama, thriller) and medium (live and pre-recorded television, theatre and film) with the sort of ease that inevitably leads to assertions that he’s a journeyman.

This is glib, somewhat dismissive reductionism. Over the years he has directed a live TV broadcast during which a lead actor died but the show carried on; given notes on another director’s masterpiece (which were acted upon); launched an iconic movie character into the popular zeitgeist; and produced one of the most successful TV series ever made. Hardly anyone’s definition of a diligent craftsman banging out proficient product. We caught up with the veteran filmmaker to find out more about his colourful career.

LWLies: Was there something in your working class upbringing that contributed to you becoming a filmmaker?

Kotcheff: My film school was an abattoir. I sometimes see a film and think, ‘This guy has no idea how real people live’. It was a tremendous boon for me, working at a Canadian slaughterhouse, and at Goodyear Tire & Rubber. When I went to work in film, I knew about human beings’ real lives, both working and middle class.

Looking back at your 60-year career, how do you perceive your own body of work?

I was certainly influenced by Italian and French filmmakers, and the British filmmakers I knew from my time in England, people like Tony Richardson and John Schlesinger. My own thing was that I always worked on the scripts I filmed, either alone as I did on my football movie North Dallas Forty, or with others as I did with Sylvester Stallone on First Blood and Bob Klane on Weekend at Bernie’s. I’ve always wanted to make films that said something, that had some meaning about the human experience.

You certainly haven’t ever been stuck in one genre.

That started when I first started directing live television. Every three weeks it would be something completely different; a comedy, followed three weeks later by a story about a young woman being molested, and then after that an action story. That was of great benefit to me, as it helped me to find out what it was that I really liked to do, and in fact I loved comedy, I loved drama, and I loved action, so I’ve happily done them all throughout my career.

Speaking of live TV, the most incredible story you recount in your autobiography is of a live broadcast of the teleplay ‘Underground’ in 1958.

It was a live four act play. Towards the end the costume designer rushed up to me and said, ‘I think Gareth Jones has fainted, he fell forward into the smudge make-up in my make-up tray.’ Jones was the villain of the piece, there were five or six characters who were buried in an underground station as the result of a nuclear war. I told my assistant to call master control and tell them to have a Charlie Chaplin short standing by. I rushed out and told the other actors ‘Something’s happening with Gareth’, and then I was told that he was actually dead.

You can imagine how we felt at that moment, but I got all the actors together and re-wrote the script, telling them ‘Here’s what we’re going to do, you’re going to say that line there, and you’re going to say that one’, and we restaged the remainder of the play in a few minutes before we were back on the air. The set was piles of rubble in this ruined underground station, so cameras came up from behind rubble and then went back behind it so another camera could move in and shoot something by the first pile. Don’t ask me how but somehow we got through it, and we made it to the end.

You were also involved in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up?

I had a call from one of the film’s producers, who told me that the film was 20 minutes too long. He told me Antonioni loved my film Life at the Top and thought that I was an ideal person to suggest the cuts as he was too close to the film to make the decisions himself. I thought the producer was trying to pull a sneaky trick and get another director to cut the film without Antonioni’s knowledge, so I said I wouldn’t do it unless Antonioni asked me himself. I was thrilled when half an hour Antonioni called and asked me for my suggestions.

I gave him about 18 minutes worth of cutting suggestions, and surprisingly he used almost all of them. About a year later I had dinner with Antonioni in Rome, and I asked him why he had eight writers listed in the Blow-Up credits. He explained that he and another writer would write each of his films initially as a silent film, and he would then bring in individual writers who had specific skill in writing comic, romantic or action related dialogue. He told me, ‘Ted, we consider dialogue to be sound effects. We believe that films are pictorial creations. You must tell the story in pictures.’ That had a big effect on me, I was 29 at the time.

You were approached to adapt ‘A Clockwork Orange’. How did that come about and why did it not work out?

Producer Si Litvinoff gave me the book and said that he thought it would make a terrific film. I worked on a script with Terry Southern. Mick Jagger wanted to play the part of Alex and the film was financed, we had the whole package, and then the British Board of Film Censors screwed it all up. They said the film would never be shown in Britain because of the depiction of youthful violence against people of property, which was a total no no as far as they were concerned. We tried to persuade Paramount to make the film in America, but they said, ‘We can’t give you British money to make a film in America that will never be shown here.’ Of course, Stanley Kubrick ended up making the film, and he made a classic.

By the time you moved out of TV and in to features in the early ’60s, television’s descent into mediocrity had begun. How do you account for the dramatic rise in quality in the 21st century?

In my early days in British TV there were such good writers writing for television, people like Alun Owen, who I did seven teleplays with. Then when live drama stopped and they started to do cheap series people just seemed to decide, wrongly, that TV wasn’t an ‘artistic’ tool, and dismissed it. It wasn’t until 10 years or so ago that people again realised the great potential of TV for telling different and difficult stories. I was offered SVU so I came back to TV. No one had ever done stories about child molestation and rape, and TV allowed us to delve into this dark area time after time. Feature filmmaking doesn’t want to tell these sorts of stories now – television is the only way to do it.

Ted Kotcheff’s autobiography ‘Director’s Cut’ is available now.

Published 17 Apr 2017

By Mark Asch

A meek and mild school teacher spirals into Aussie Hell in this riveting, repellant restoration.

By Matt Thrift

The veteran Hollywood maverick talks Dog Eat Dog, Scorsese and the challenges of modern moviemaking.

By David Hayles

Forty years after it left critics cold this majestic tragi-comedy stands as a testament to a true master of his craft.