Words

JACK GODWIN, GABRIELA HELFET, DAVID JENKINS, ELENA LAZIC, MANUELA LAZIC, JOHN WADSWORTH

Illustration

Wes Anderson, Kathryn Bigelow and Wong Kar-wai feature in the final part of our ’90s ranking.

After you’ve read through this part of our 100 best films of the 1990s ranking, check out numbers 100-76, 75-51, and 50-26.

Seven and a half hours of slow-brewed, plum-brandy-swilling goodness in which the ripple effect of communism’s downfall lays waste to a tumbledown Hungarian village – Béla Tarr’s Satantango is both a stultifying endurance test and one of the great films about how politics affects real people. The ominous story thread leads us into houses and hostelries as the scruffy denizens dance, drink, argue and joke their lives away in the wake of the closure of a nearby factory. The film is grotesque and intoxicating – some scenes trail on until they transcend tedium to become almost abstract in their sombre beauty, while others are just downright disturbing, such as a sequence in which a small child gets a mite too aggressive with a cat. The decision to sit down to watch this singular work is one that shouldn’t be taken lightly, but once seen, it can never be forgotten. David Jenkins

This is still the little film that could, going from the Cannes competition title that none of the press corps bothered to see to winner of both the best actress prize (for its newcomer star Émilie Dequenne) and the big one – the Palme d’Or. Suddenly, the Dardenne brothers were the talk of the town. The big catch: the film was actually astonishing and wholly deserved of every accolade thrown at it. The title refers to an unemployed woman living hand-to-mouth in a grim trailer park, caring for her alcoholic mother and desperately attempting to find work. Yet one of her key character traits is that she’s aggressively individualistic, so any and all success must be on her own terms. Shot on the shoulder as if documenting the machinations of a warzone, this was the film that announced the Dardennes as humanist sages, and it shines brightly to this very day. DJ

This ultra-laconic documentary from the unprolific Spanish director Victor Erice subtly expounds on the cosmic majesty available to all and sundry, from city to suburb. The set-up is disarmingly simple: Erice observes artist Antonio Lopez as he attempts to paint a picture of the mighty quince tree growing in his backyard. But as the sun tilts in the sky, the wind shifts the foliage, the fruit ripens and then rots before he’s able to connect brush with paper, his plans are tragically altered. By recording this process, the director articulates the ephemeral nature of existence and how life is often shaped to compliment both surroundings and environment. It’s a heartbreakingly truthful and objective film about the impossibility of capturing truth and objectivity in art. In life, we just have to do the best we can. DJ

Max Fisher (Jason Schwartzman) is 15 but determined to lead the life of an adult in the safe haven of a quaint private school named Rushmore. He wears a tailored jacket, sets up dozens of school clubs, writes plays and flirts with teacher Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams) – Max wants it all. Yet this manic behaviour, as infuriating and amusing to witness as it may be, constantly confirms that he remains a child at heart, always in need of affection and guidance. A perfect soundtrack paired with audacious cinematography – the neat compositional symmetry gels surprisingly with instances of hand-held camera – provide a youthful energy to this in fact very serious film about what growing up really means: face the facts, but remain hopeful. Manuela Lazic

Oliver Stone has sadly been off the boil for some time now, but JFK remains a fever-pitched monument to all that he does so well. Tossing the Warren Commission into a metal bucket and then throwing a flaming match on top, the film spins a compelling conspiracy yarn that the Kennedy assassination was much more than just a lone wolf wacko who pulled off some million-to-one crackshots from a book depository window. This whirlwind narrative not only takes us through the looking glass but smashes it into a million tiny pieces, transcending its remit as a tubthumping political corrective to become a paean to the very process of deep analysis. Kevin Costner, at the height of his Hollywood powers, delivers a career best performance as Louisiana DA Jim Garrison, whose eloquent, climactic courtroom summation harks back to Capra at his best. DJ

Two deeply melancholic policemen, unknown to one another, are lovesick in Hong Kong. They both meet women: one a mysterious criminal, the other a worker at a late night snack bar. Chungking Express is saturated with sadness, portraying neon-hued city life as coloured by loneliness in the midst of a bustling crowd. Wong Kar-wai’s characters are almost immobilised by lingering heartbreak, unable to accept the inevitable change that comes with the passage of time. They are lured into movement by chance encounters, coincidence seeming miraculous amid the urban chaos. Through the enigmatic performances of its leads and the intimate and beautiful cinematography care of Christopher Doyle, Wong deals with the bittersweet notion that lives that pass us by in such large numbers that we don’t have the ability to connect with them all. Jack Godwin

Eyes Wide Shut is one of the best explorations of male entitlement in all cinema, and it’s one of Stanley Kubrick’s most emotional and humane films. The smooth and restrained camera follows Dr William Harford (peak Tom Cruise) as a casual meeting with an old friend leads him deeper and deeper into an elite secret sex society. Rather than a trashy ’90s erotic thriller, however, Eyes Wide Shut finds its intellectual depth in Will’s ever more bewildering encounters with all kinds of people. His notably Freudian conversations with his wife Alice (peak Nicole Kidman) in particular make him reconsider all his certitudes about feminine sexuality, but also about the very nature of reality itself: doubles, repetitions and disappearing characters all conjoin to confront Will with the truth and wake him up from this lucid dream. ML

Abbas Kiarostami’s 1990 masterpiece is testament to the fact that making cinema ain’t easy. This master director, whose untimely passing in 2016 is still an incalculable loss for the medium, makes decision after decision which almost goads the viewer into rubbing their hands and politely walking away. There’s rambling dialogue scenes, skewed framing, use of low-grade film stock and faulty sound equipment, and all wrapped around story which, from certain vantages, appears to offer no discernible drama. And yet, it somehow manages to be one of the most purely magical films about the magic of cinema, telling of a man who, in the depths of penury, decides to impersonate his hero, the Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and is arrested for fraud. The poignant reasoning why he did it directly articulates how cinema has the power to change lives, and at the same time, Kiarostami practises what is being preached from behind the camera. Miraculous is the word. DJ

You’d do well to find someone who would admit to not liking Joe Dante’s dangerously charming movie-buff comedy, which connects the cheapo gimmicks of 1950s genre cinema with the potential death-from-above of the human race as we know it. John Goodman perhaps landed his greatest role as the charismatic sideshow huckster Lawrence Woolsey, who decides to showcase his new interactive monster movie, Mant, just as nuclear tensions between the US and Russia begin to flare. Everything about the film is crafted with a palpable love for the medium, and Dante confirms his earnest belief that, in the end, it’s only cinema that can save us all. DJ

French maestro Eric Rohmer is one of those rare cases of a director who worked across multiple decades and never made a single bad movie. The actress Marie Rivière was, however, something of a lucky charm, starring in both his best of the ’80s (The Green Ray) and his best of the ’90s (An Autumn Tale). The final film in his ‘four seasons’ cycle sees two middle-age women take time out from producing wine to engage in a little Shakespearean matchmaking. Rohmer’s famed lightness of touch belies more doleful undercurrents, with the possibility of finding true love tactfully compared to a time of year where lush greenery falls from the trees and fizzles into nothingness. DJ

It’s something of a travesty that Abbas Kiarostami’s “Koker Trilogy” is not widely available on a range of high-quality formats, as it stands as one of the great movie series of the modern age. This final chapter, following 1987’s Where is the Friend’s House? and 1992’s Life, and Nothing More, explores life in small rural Iranian town that has been devastated by an earthquake – the three films adopt a before, during and after timeframe. Through the Olive Trees is the complex, elegiac finale, concerning the production of movie in the village that references the machinations of the previous two films. It picks apart the relationship between cinema and landscape, directors and subjects, men and women, upper and lower classes and, in its dazzling final shot, the earth and the heavens. DJ

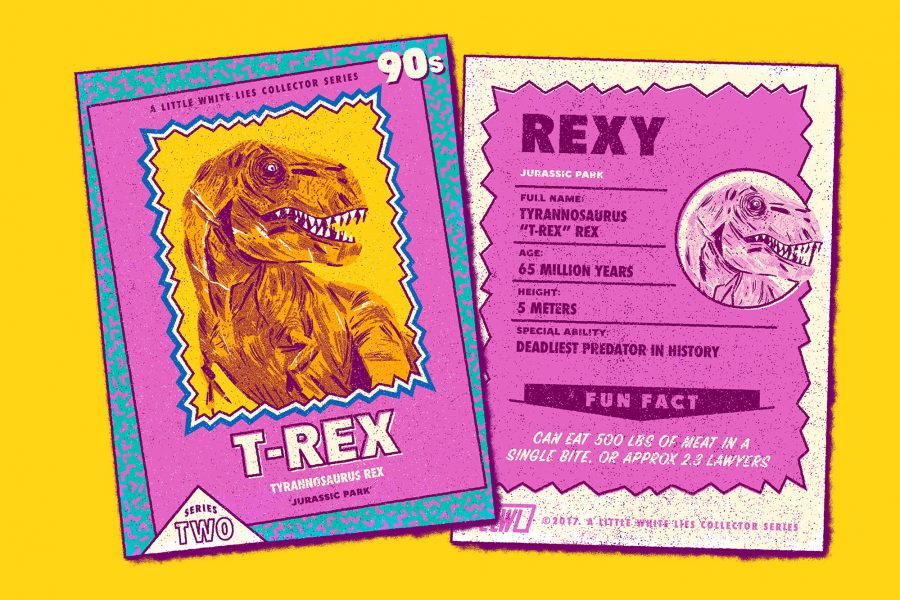

Jurassic Park, like the reanimated dinosaurs who roam through the film, is an extremely rare creature: a grandiose, white-knuckle, mega-blockbuster that is equally funny as hell, quirky, and awe-inspiring. From the beginning, it’s obvious that resurrecting T-Rex and co for the sake of human amusement is never going to end well, but that doesn’t make escaping the inevitable fallout any less exciting to watch. “Hold on to your butts!” indeed. The timelessness of Spielberg’s opus is all the more impressive given how much moviemaking technology has changed in the 25 years since its release, and how true its closing message still rings today: don’t fuck with nature, or she’ll come back to bite you in the ass. Gabriela Helfet

Some may say that the late, very great Aleksey German took his sweet time when it came to making movies. Others may say that the movies he made could not be rushed, for that is what made them unique. This extraordinary, penultimate missive is a work that you could watch 100 times and still not fully ingest everything that German loads into each and every frame. This exhilarating film follows a doctor during the final days of Stalin’s regime in Russia, taking in the chaos that comes with the ignoble fall of a brutal dictator. Someone release this incredible film on Blu-ray right the hell now. Thanks. DJ

The soundtrack to Dead Man sees Neil Young pounding and thrashing an electric guitar in a manner that seems like his senses are diminishing and he’s and fighting to communicate with the outside world. It dovetails perfectly with the story of Jim Jarmusch’s eccentric 1995 death rattle about a kindly man (Johnny Depp) who travels across country to accept a job, and soon finds himself drifting into the bounds of a lawless infinity as a gunshot wound slowly saps the life from his soul. It’s a slow and stately cine-fugue which draws and develops on the classic western template, with the whimsical, episodic trawl exemplifying life’s fragility and also its poetic absurdity. DJ

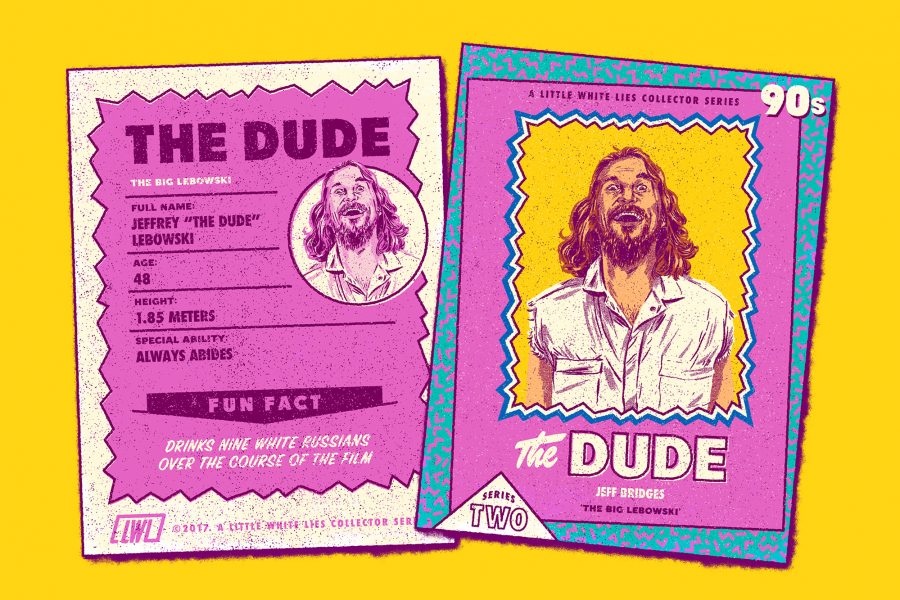

As the records have it, the Coen brothers’ narcotised LA noir-comedy from 1998 will officially go down as a flop, because it didn’t perform at the box office. However, it has since gone nuclear on home video, spawned its own religion, is a regular on the midnight screening circuit, reclaimed the White Russian as the cocktail for people who don’t drink cocktails, re-energised the career of its lead actor, Jeff Bridges, led to a forthcoming spin-off movie based on one of its most beloved characters, is the subject of various book-length studies, and is maybe the most quotable film of the modern era. So, if anyone ever comes to you and says that The Big Lebowski was a big flop, you say right back to them: “Yeah, well, that’s just, like, your opinion, man.” DJ

Sorry Showgirls fans, but this is the Paul Verhoeven film we’d want to place in our giant time capsule of great ’90s artworks. Its evolution over the past 20 years has been astounding to observe, initially dismissed as glossy jingoism, later reclaimed as satire, and now seen a chilling state of the nation address. In the most unabashedly fun manner possible, Verhoeven has us rooting for fascists as they conquer a race of killer bugs on the other side of the galaxy. The film’s pioneering use of computer graphics mixed with old-school latex splat has helped it more than stand its ground in the tech stakes – in fact, it’s dated far less than something apparently revolutionary such as James Cameron’s billion-dollar blue movie, Avatar. DJ

You can’t move for banal proclamations that we’re living in the golden age of television, but France had things already locked down tight in the early ’90s. The channel Arte commissioned a series of medium-length films intended to examine the youth of the day, named ‘Tous les garçons et les filles de leur âge…’. Chantal Akerman’s 59-minute romantic opus follows a young couple connecting, disconnecting and then moving on to pastures new. Lord knows that cinema has given this subject its dues over the years, but with sublime economy and poise, this master director brings something new and exciting to the table. She achieves in less than an hour what the majority directors can’t do in one, maybe two, or even across multiple films. Hell, why not make that an entire career? DJ

Like a wonderful magic trick, David Fincher’s third feature film is comforting in its slick simplicity, baffling for most of its runtime, disturbingly creepy, and ultimately delightful, with a denouement as inventive and heart-stopping as it is ridiculous. After two hours of slick suspense-building, with the icon ’90s thrillers Michael Douglas in the lead role, it is as though cynical Fincher decides to out the entire genre as a silly joke. By not taking things too seriously, Fincher produced one of the most purely enjoyable films of the ’90s which also acts as a fitting tribute to (and deconstruction of) this most beloved of narrative forms. Still, behind its appearance as a rather empty exercise, it is also an early manifestation of its director’s career-spanning interest in the way people relate to and misunderstand each other. Elena Lazic

He may never have been in sniffing distance of an Oscar (except the honorary one he netted in 2016), but Frederick Wiseman will likely go down as the greatest film documentarian the world has ever seen. This 1997 film surveys life behind the distressed doorframes of Chicago’s Ida B Wells housing project, and it’s as close to a piece of pure cinematic poetry as the vaunted director has even gotten. He sashays around the grounds, one minute capturing the tensions of a residents meeting, and then watching intently as an elderly woman slices cabbage alone in a dilapidated kitchen. There’s a cosmic energy to the film, as people shoot in and out of the frames like shooting stars. It’s a bittersweet film about cohabitation, looking at how buildings attempt to strip us of individuality even though it is, in the end, an impossible feat. DJ

You’ll notice that The Matrix doesn’t make the cut in this rundown of ’90s classics, and that’s because we’re instead placing all our chips (plus the keys to a brand new Cadillac Eldorado) on Kathryn Bigelow’s jaw-dropping apocalypse satire, Strange Days. Ralph Fiennes is (surprisingly) brilliant as a greasy LA smut peddler who uses outlawed technology to plant sex and death into the minds of his punters. The passing of an iconic hip-hop star ignites a chain of events which takes in race hate, police brutality, the normalisation of misogyny, celebrity obsession, censorship, pre-millennial tension, cyber warfare and the rise of surveillance culture. And it even had the wherewithal to include what could be considered one of the most beautiful and casual interracial love affairs in modern cinema, with Angela Bassett on peak form as a grieving mother who becomes a bad-ass bodyguard. DJ

The title of Todd Haynes’ 1995 masterpiece asks to be completed: safe, but from what exactly? The film isn’t as precise and simplistic about the anxiety suffered by Carol (Julianne Moore) as it may first seem. Fumes and a rather sedentary suburban lifestyle don’t seem to explain how such an exceptionally healthy housewife could suddenly experience violent and ever-worsening physical reactions to her wipe-clean surroundings. Over two engrossing hours, Haynes slowly reveals the depth of Carol’s malaise as a woman totally engulfed by patriarchal forces wherever she goes: her house, at baby showers, and even at a cure centre far from the city that seems contaminated by suffocating guidelines. Rather than crudely pointing a finger at specific culprits, Haynes focuses on one of their victims, giving his heroine the humanity and complexity that society – at least in 1987 California, but also, evidently, to some extent today – refuses to acknowledge in her. ML

Edward Yang’s intimate epic concerns individuals swaying in the choppy tides of political upheaval. Set in Taiwan during the early 1960s, the film orbits around Chang Chen’s S’ir, a bookish tyro whose wild mood swings seem to echo that of his country’s erratic political machinery. The film, which borrows its English title from the lyrics to Elvis Presley’s ballad ’Are You Lonesome Tonight’, references the deluge of Western culture that catalysed Taiwan’s national identity crisis and difficult relationship with the Chinese mainland. But the film unfurls as a gigantic prose poem, accruing details, focusing on small but vital moments, switching perspectives, capturing large warring factions and starry-eyed couples, and allowing us into the lives of some 100 speaking characters. DJ

Even though Slacker was his second official feature film, this is the moment it all started for Richard Linklater. Look to his biggest future successes – the Before movies, Dazed & Confused, Boyhood, Everybody Wants Some!! – and it all snakes back to this sublime “exquisite corpse” movie eavesdropping into the lives of the eccentric Gen X inhabitants of Austin, Texas across a single sweltering day. The film preempts Tarantino in his love of digressive dialogue exchanges and louche pop cultural namechecking, but gradually transforms into something more substantial, a waking daydream which ends up by ushering in the death and rebirth of cinema itself. DJ

As one of Britain’s foremost purveyors of screen poetry, it comes as little surprise that Terence Davies hasn’t made a huge number of films during his considerable tenure as a director. His single, glowing missive from the ’90s, however, remains one of the decade’s towering examples of the medium’s expressive and emotive potency, a rite-of-passage yarn like no other before or since. This feature-length social realist tableau presents working class Liverpool of the 1950s as a rich pageant of post-war rejuvenation and youthful sexual longing, as latchkey scamp Bud grapples with the various social influences on his upbringing. The sequence set to Debbie Reynolds’ Tammy, in which Bud swings on a metal bar, entirely alone but happy, is one of Davies’ most immaculately realised sequences. And the breathtaking final shot sees the film take a nod from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and propose that man’s transcendence can be found in stars, or failing that, the flickering light of the cinema screen. DJ

It’s possible to look at a film and judge its maker is a master storyteller or a technician of esteemed repute, but with Claire Denis’ Beau Travail, it genuinely feels as if we’re party to another person’s lucid dream. This is a rhapsodic mind-patch more than it is a movie. Every image brings with it a jolt of surprise, every cut pulses like the blink of an eye. It’s lugubrious and tactile, a film with skin and bones, blood and tears, dust and sand trapped between the beginning of one frame and the start of the next. It feels like a story that’s being remembered at the moment of death, probably by the discharged, troubled Legionnaire (played by Denis Lavant), whose military rank and status has been dissolved on the back of a romantic power-play attempted and failed out on the scorched vistas of Djibouti. It’s adapted from Herman Melville’s novel ‘Billy Budd’ and depicts an erotic desert-bound ballet and the fatal clash between desire and duty. Its closing scene is the final, ecstatic epiphany, a wild, solo mating dance to a crowd of no one. DJ

Now see the full list at a glanceThanks for reading our countdown of the 100 best films of the 1990s. We’d love to hear what your favourite films of the decade are. Share your personal Top 10 with us @LWLies

Published 15 Mar 2017

The director’s own professed black sheep is his most beautiful work.

By Matt Thrift

The outspoken Dutch filmmaker discusses his triumphant return to cinema, Elle.

Steven Spielberg’s beloved 1993 movie is about so much more than dinosaurs.