Paul Verhoeven comes at genre not just like a satirist, but more specifically like a caricaturist. The impish Dutch filmmaker specialises in isolating an artistic category’s defining quality and exaggerating it to warp his subject, ultimately upending our preconceived image of it. During his subversive Hollywood period, he regularly turned the obscenity of the US inward by giving the people a sickening dose of what they wanted.

Such anti-blockbusters as RoboCop and Starship Troopers ratcheted up the red-blooded thirst for violence in the police and military, while Showgirls turned the lubed-up American libido into a writhing, thrashing parody of itself. With his return to Europe came an accompanying shift away from outsized indulgence to equally over-the-top tastefulness. Rather than savaging common-denominator forms like action or romance by going garish, he’s taken to classing up the disreputable. With Elle, he brought a fresh aesthetic discipline and emotional nuance to the rape-revenge thriller, and his latest film Benedetta continues a proud, sacrilegious tradition in the most inspired terms yet.

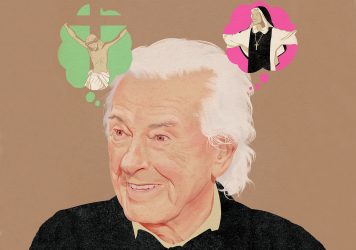

From the moment that the phrase “Paul Verhoeven lesbian nun movie” entered the cinephilic lexicon, the naughtiest version of the concept dared us all to anticipate it. (The eye-grabbing promotional poster bearing a cheeky semicircle of nipple still left a great deal to the imagination.) The breathless tweets from the Croisette premiere at 2021’s Cannes Film Festival seemed to confirm that dirty old man Verhoeven was back at full lech, with excited chatter about whittled dildos and vaginal torture instruments flying this way and that. But the content belies its style, which brings a severe, hushed grace even to its most profane gestures.

The film’s not not nunsploitation, dedicated to the proposition that hotbeds of feverish erotic energy rage under the prim surface of sisters in Christ, and unshy about showing how it escapes. However, this classification implies too much to strictly apply, its connoted lurid sensibility alien to Verhoeven’s high drama of sincere jealousy and devotion. There’s no shortage of sin, but there may be a chance at salvation to go with it.

Changing course from expression to repression as he doubled back across the Atlantic, Verhoeven trained his sights on a subculture organized around systematic self-denial of pleasure as its chief tenet. As a 12-year-old Benedetta Carlini is informed upon enrolling at a Tuscan convent, the body is a shameful thing and we must estrange ourselves from it as devoutly as possible. Of course, the eternal paradox at the heart of Catholicism is that there’s nothing hotter than wanting something you can’t have, as it’s dangled just beyond your reach; a quandary that a desirous Benedetta (Virginie Efrie) confronts in adulthood.

Her undeniable attraction to fellow nun Bartolomea (Daphne Patakia) sends her into literal paroxysms of horniness – try as she may to channel those feelings onto the Sexy Jesus rocking her in fantasies straight out of a bodice-ripper paperback. She sees lust everywhere in religion: the constant orders to kneel and stand, the BDSM-adjacent rituals of punishment, the titillating closeness of fleshly temptation.

In keeping with nunsploitation custom, Verhoeven draws attention to the hypocrisy, prejudice, and ignorance of the Church; the head abbess Felicita (Charlotte Rampling) shakes Benedetta’s father down for money in a meeting to arrange the girl’s service, and then excoriates him for trying to negotiate “like a Jew.” Her pettiness and cruelty reveal themselves to have roots in envy once Benedetta starts communing with God – the power struggle between the women not so dissimilar to a sexual battle of wills – with the Almighty as the contested trophy hunk. Organized religion is just another way for those in positions of authority to assert their influence, channeled through pathologies of pent-up need that translate to domination and submission.

And yet Verhoeven’s handsome visual polish goes hand in hand with a more receptive attitude toward Christianity out of joint with the premise’s origins in high-grade trash. Because his contempt for the Church stems from serious regard for the virtues they pervert, he’s not throwing the holy baby out with the blasphemous bathwater. He’s said in interviews that he believes in the existence of Christ but not his divinity, more “interested” in how the man “was extremely important for our culture and the development of humanism.”

The film would suggest a higher degree of credulousness on his part — Benedetta seems truly touched by the spirit, her voice lowering itself to a goblin register while possessed — even as it torches the institution built around the faith. Verhoeven knew that the most iconoclastic way to approach the hot-under-the-wimple nun film was to play it straight, turning down the sensationalism in favor of a more studious examination of how eternal carnalities collided with the dogma of a buttoned-up point in history. There’s too much full-frontal nudity to completely discount Verhoeven’s prurient side, and too much fervency to write him off as a horndog with one thing on the brain.

Benedetta is released in UK cinemas 15 April and streams exclusively on MUBI from 1 July.

Published 13 Apr 2022

Dutch master provocateur Paul Verhoeven serves up a blasphemous delight in his convent-set Italian romp.

The Dutch provocateur chats lesbian nuns, alternate realities and his undying love for Quentin Tarantino.

Two decades on, Paul Verhoeven’s ambiguous militaristic sci-fi is in need of a reappraisal.