Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop turns 30 this month, and it remains a seminal piece of screen sci-fi despite the lacklustre sequels, TV shows and remake that proceeded it. It’s one of a number of films that looked to the future in the late ’80s and wondered what it would be like. With the last decade of the millennium approaching, cinemas were inundated with visions of the future such.

Some were pretty far from the mark – 1997 was a lot quieter than Escape From New York predicted – but others now seem eerily prescient: The Running Man imagined a future dominated by reality-based TV, while the things Back to the Future Part 2 got right (and wrong) about 2015 are well documented. No, we don’t know where our hover boards are either. RoboCop isn’t confined to a specific date, but does have something to say in terms of where society is going. So, how on the money was Verhoeven’s depiction of a dystopian Detroit?

The decline of Motor City is portrayed with grim accuracy in Verhoeven’s film. Although things were looking bad by the late ’80s, the declining automotive industry has hit the city hard in recent years. Crime rose, the population dropped, and the city’s name became a media byword for disarray. Many residents didn’t appreciate the image the film portrayed of their city, but for many reasons the stigma still remains.

A half man, half cyborg law enforcer designed to take the human error out of police work is pure science fiction. Yet certain elements of this futuristic vision are already being integrated into modern policing. Drones are now commonplace in many areas of law enforcement, while recently the Dubai Police Force unveiled a robot that can report crimes and accept fines, intended to be fully integrated by 2030. A hybrid officer containing human remains still seems a long way off though.

RoboCop’s first recollection of his past self comes after seeing thug Emil Antonowsky at a gas station (“I know you! You’re dead! We killed you!”). He uses facial recognition programme on a recording of the encounter, something now used in everything from shopping centres to phone lock screens. It’s thought that half of US adults’ faces are stored on police databases, making the film strikingly accurate.

Sure, there are now multiple screens in every room, but they tend to be a lot smaller, and flatter, than the stacked CRT televisions scattered among the locations in the film (all showing the Benny Hill-esque show which everyone seems to find so hilarious). It’s a feature that dates the film more than the big hair and power suits. A flashback also sees Murphy’s son playing with a model aeroplane – evidently iPads and fidget spinners were not a part of Verhoeven’s future.

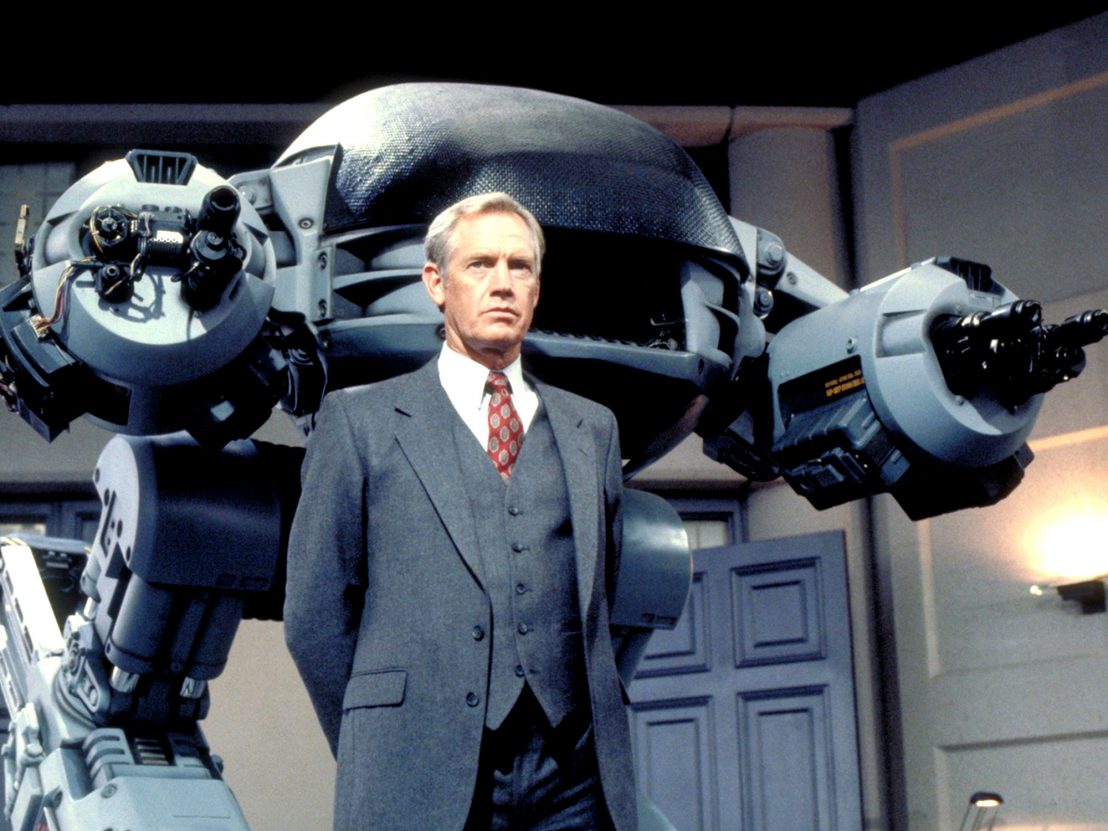

The villain of the film is Omni Consumer Products (OCP), a powerful corporation that controls the Detroit Police Department, as well as having a monopoly over hospitals, prisons and space exploration. Privately, corrupt executives hope that escalating crime rates will help it turn the dilapidated Old Detroit into the affluent new Delta City, turning to Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith) and his goons to keep the chaos going.

The company is Verhoeven’s comment on the potential for suffering when profit is put over people, and it’s concern that holds true today. From controversies surrounding company G4S’ involvement in policing in the UK, to the privatisation of space travel and hospital care in the US, the wellbeing of society often clashes with The Bottom Line around the world. For a film titled RoboCop, it’s a pretty astute observation of where we could be headed.

Some of the news headlines featured in the film are (intentionally, no doubt) a little out there. To date, no President has ever visited space; there is no nuclear stand-off in South Africa; and no American crisis in Mexico – at least, not one that involves fighting in Acapulco. Climate change is also not on the agenda, at least if the commercial for the very thirsty 6000 SUX (a car boasting 8.2 miles per gallon) is anything to go by.

It’s rare for science fiction to accurately predict the future – after all, most dystopias are intended as comments on the era in which they are written. If nothing else, however, the original RoboCop had a little more going on beneath the surface than many of its contemporaries.

Published 17 Jul 2017

David Cronenberg’s erotically-charged social satire is a cautionary tale for the internet age.

How the movies forecast everything from celebrity politics to the rise of social media.

By Nick Chen

From Showgirls to Starship Troopers, delve into the Dutch filmmaker’s provocative back catalogue.