“Since I see technology as being an extension of the human body, it’s inevitable that it should come home to roost.” David Cronenberg was referring to his 1988 film Dead Ringers when he offered up this fascinating insight into his work, but to a varying degree it applies to all of his early films, from Shivers and Rabid to The Brood and Scanners. Yet it’s Videodrome which perhaps best encapsulates this self-reflexive statement.

Released in 1983 and hailed as the decade’s answer to A Clockwork Orange by none other than Andy Warhol, Cronenberg’s eighth feature further enhanced his reputation as North America’s foremost purveyor of body horror while simultaneously establishing him as the thinking person’s genre filmmaker. It is a bold, cerebral examination of human kind’s masochistic, subservient tendencies.

Right from its immersive opening shot, Videodrome imagines a near-future in which technology has infiltrated every aspect of daily life. On a screen within the screen, a colourful ident for CIVIC-TV (“the one you take to bed with you”), a Toronto-based station specialising in shlock programming, flashes up before a woman (Julie Khaner) serenely delivers an automated wake-up call. Cronenberg may not have been actively trying to predict the future, but this scene contains an eerily prescient blueprint for the likes of like Siri, Alexa and other intelligent personal assistant systems.

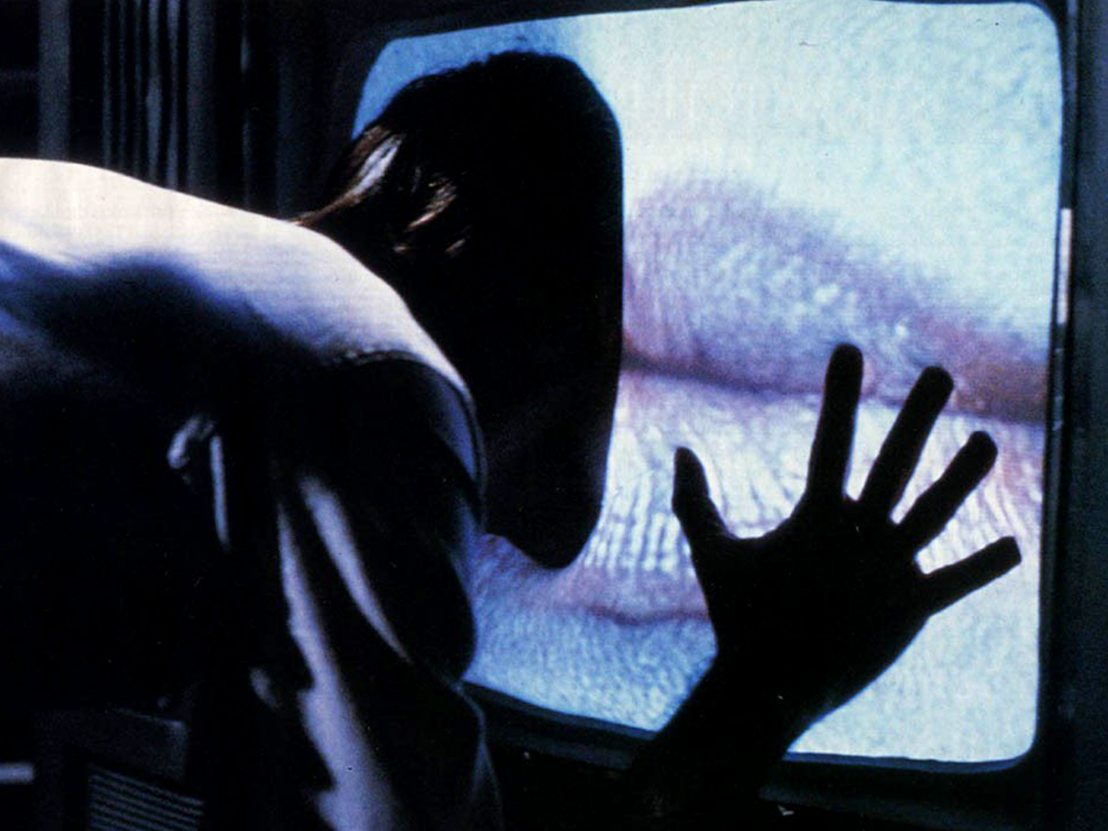

Having been eased back into consciousness, CIVIC-TV CEO Max Renn (peak James Woods) descends into a waking nightmare as he is slowly and painfully consumed by Videodrome, an entirely plotless, extremely low-rent television show – think of it as an even more exploitative precursor to reality TV – which he believes to be the next big thing.

Watching Videodrome today – from a pristine 35mm print at the 71st Edinburgh International Film Festival – it’s striking just how relevant it feels. Its smoky, late-night aesthetic and animatronic special effects place the film firmly in the 1980s, but the socially-conscious theme running through it is alarmingly pertinent when viewed in a contemporary context.

It’s a film made in and about the VHS era, but substitute in the internet and the message would be much the same. We live in an age where technology facilitates everyday human interaction on a macro scale. A time of unparalleled interconnectivity in which information is transmitted, processed and shared quicker and more widely than ever before. In Cronenberg’s dark satire on consumerism and the cult of technology, Max reflects both the director’s concerns over the electronic dissemination of information (especially via faceless, morally-dubious corporate entities) and his compulsion to create provocative, erotically-charged art.

Herein lies the curious dichotomy of David Cronenberg. His early films pulse and spurt with visceral imagery – exploding heads, self-impalement by scissors, a man inserting a video cassette into a vagina-like cavity in his chest – intended to penetrate deep into our psyche. Yet at the same time they warn us against the potentially corruptive influence of visual media. Forcing us to watch Debbie Harry stub a cigarette out on her bare stomach as Max recoils in horror may ultimately say more about the director’s impulses than our own, but there is a certain perverse pleasure to be derived from such explicitly fetishised moments.

Of course, it is no coincidence that Videodrome now appears scarily prophetic in the way it depicts the intersection of sex, violence, media and technology. Cronenberg is a master at intuitively tapping into our collective subconscious. He knows how people are wired, so even though Videodrome operates on the level of its central character’s deranged dream logic, the director is able to reflect our innate fears and desires back at us with sobering clarity and precision.

Cronenberg has also said that he doesn’t believe in an afterlife, that mind and body are interrelated and thus inseparable. This is particularly evident in Videodrome, where Max’s mental collapse manifests as a grotesque physical mutation care of special effects maestro Rick Baker. What the film doesn’t foretell, however, is that each of us now has a digital fingerprint which we add to any time we browse the internet, use social media or stream a movie – a unique code controlled not by the individual to which it relates but by forces even more powerful and insidious than the one Cronenberg imagines here.

Still, as a comment on our desensitisation to pornography and the increased intimacy of our relationship with screens and technology at large, Videodrome feels several decades ahead of its time. It states in no uncertain terms that the next stage in our evolution as a species will be a dehumanising one. For better and for worse, 34 years on Cronenberg’s frightening futuristic vision is starting to become reality. Long live the new flesh.

Published 27 Jun 2017

After 30 years David Cronenberg’s tour de force of disgust is as powerful and penetrating as ever.

Watch Ben Wheatley’s go-to prosthetic effects artist reveal the secrets of his craft.

By Tom Graham

Twenty five years on David Cronenberg’s adaptation of William Burroughs’ classic novel remains a bold and transgressive vision.