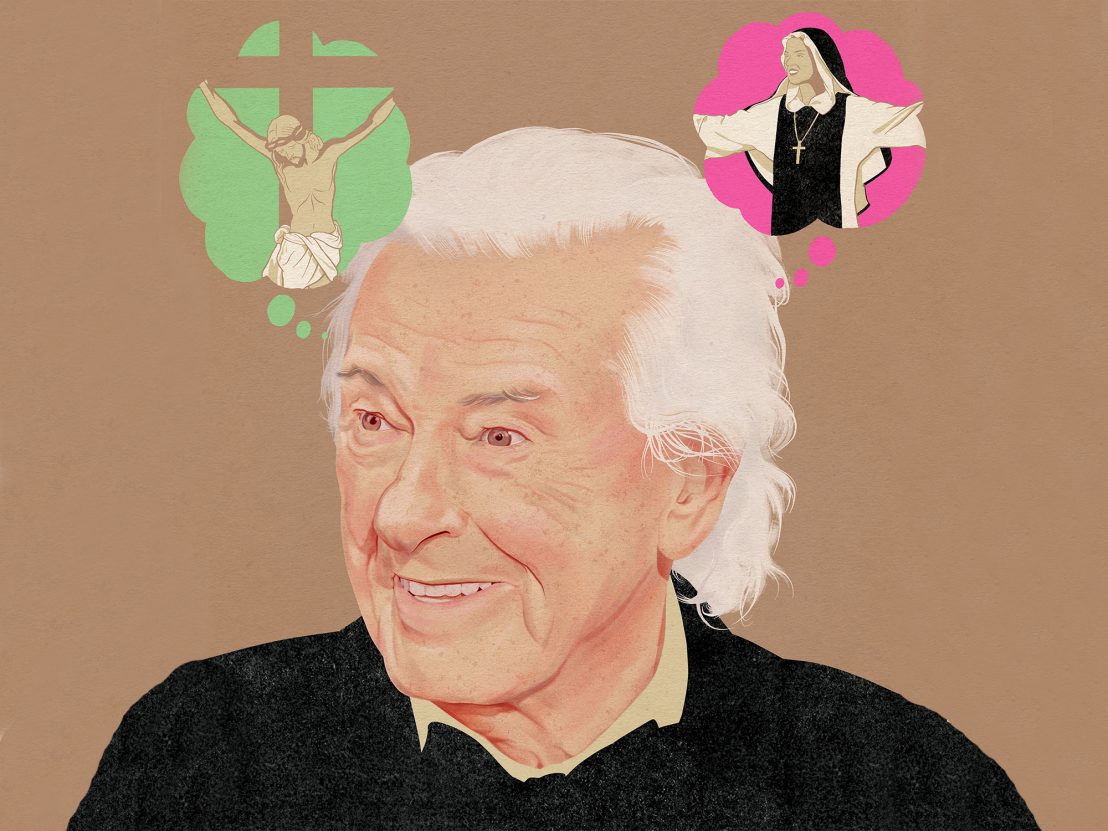

The Dutch provocateur chats lesbian nuns, alternate realities and his undying love for Quentin Tarantino.

Except for maybe RoboCop, Benedetta represents Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven’s closest attempt at fulfilling his lifelong wish of bringing the story of the historical Jesus to the screen. Based on the trial transcripts described in Judith C. Brown’s ‘Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy’, the film revisits many of Verhoeven’s life-long obsessions: unstable realities; sexual desire; corrupted power and the divine. Set during the 17th century, an Italian nun (Benedetta Carlini) blessed with divine visions is declared a mystic and a living Saint by the Vatican, only to be accused of sapphism and put on trial for her crimes.

LWLies: What is it about the line between reality and illusion that fascinates you?

Verhoeven: If you look at Total Recall, I made a movie from the perspective that there will be two realities: the reality that Arnold would be the saviour of Mars and the reality that he’s still in a coma. Gary Goldman [one of the co-writers] suggested that [the film] is not ‘this’ or ‘that’, but ‘this’ and ‘that’. You can call it post-modern if you want to use a fashionable term. The most important movie that inspired me was Rashomon, and in that movie, there are four realities! When I was a young man in my twenties, when the film came out, it hit me, of course. Everybody has his reality, that he sees through his own eyes and is shaped by the way his brain has developed.

Rather than cast doubt on Benedetta’s fantasies, you recreate them. In Brown’s book, it’s clearer that Benedetta has a mental illness. What motivated this choice?

In her brain, Benedetta creates a Jesus that is saying what she wants anyway. In the beginning, Jesus says, ‘Stay with me.’ Then, later, it turns out that Jesus was not a good guy. There’s the scene with the snakes, and later, she picks up something from the mercenary she saw when she was ten years old and makes him Jesus. He’s a bad guy. Jesus is a false God. She invalidates Jesus and stays away from him. There are other scenes where Jesus is on the cross, the “real” Jesus, who tells her to take off her clothes. There’s no shame, meaning it’s okay for you to get naked and have sex. Her Jesus is somebody that always changes to fit the direction she wants to go in. He sanctifies her decisions, makes them sacred. It comes from him that she can have sex, which at the time was forbidden. At that time, that kind of relationship would be punished severely. Being a lesbian meant you would be punished like a criminal, but you would be burned at the stake if you used a tool like a dildo.

I thought it would be interesting to show her doing things but let the audience make up their mind. I wanted to show her visions without telling you what to think. The visions, though, are completely parallel to where she wants to go. She uses her religion as a tool to do something that is absolutely forbidden.

You wrote a book about the historical Jesus, focused on his humanity. How did your perspective inform the film?

The big mistake of Christianity is that the resurrection of Jesus is not possible. They always forget and, but it is very clear in the Gospels that Jesus was absolutely convinced that the kingdom of God was coming. Not in 2000 years, but now, in a couple of months. That ultimately did not come. There was no kingdom of God. Then, the Church invented this wonderful, clever lie that Jesus came back. They invented this resurrection that never happened. So, instead of listening to Jesus, what he has to say is very clear in the parables, all the focus falls on the resurrection. What Jesus said was very important, but because the Kingdom of God never came, they changed everything around, and suddenly Jesus was “resurrected.” But, what is important to me, is what he said, not that they made him the son of God. I don’t think he saw himself as the son of God at all.

That, of course, is an undertone of the movie. That layer is subdued and not explicitly said, but it’s still me (laughs) [so, it’s there].

Hitchcock has a bit of influence on many of your films, even your same fascination with blondes. Is this a conscious choice?

I learned a lot from Hitchcock and notably, Vertigo and North by Northwest, which I appreciate probably more than ever. The women for him, basically if they had dark hair, weren’t very important. That could be a little bit the case for me. For example, the main character [in Basic Instinct, played by] Sharon Stone is blonde and the other important character has dark hair. I’m sure there is some influence there, but I’m not aware I’m doing these things. Recently, I saw the scene in Basic Instinct where [Stone’s] lesbian lover dies in a tragic accident, came from a comic book, [Dick Bos by Alfred Mazure], I had read in 1943. I saw the drawings of Mazure and 30-40 years later, I made the exact same shots. Sometimes these things happen.

For a long time, in my films from Holland and certainly in the beginning in the United States, I identified far more with the male characters. Robocop was a male, Douglas was a male [in Basic Instinct], although Sharon stole the show. In the last 10-15 years, that slowly disappeared, and I became more interested in the pull of the female character. I don’t know why it is. It’s not on purpose. It just happened. I’m working on a new script with Edward Neumeier, who did Robocop and Starship Troopers, a Washington thriller called Young Sinner, and the two main characters are female too. It might be my old age, but I identify far more with the “female” part of my brain.

We’ve spoken about some of your favourite films from the past. Are there any contemporary filmmakers you love?

That would be Tarantino. Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood was a beautiful movie, and the ending was really one of the funniest scenes I’ve ever seen, you know when he starts to shoot all those people? [laughs] But also, the lightness of the film, Brad Pitt at the studio, the girls hitchhiking. I felt that it captured what I felt like when I came from Holland to the United States. It’s certainly, for me, one of the best movies of the last 10 years.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

Published 11 Apr 2022

Dutch master provocateur Paul Verhoeven serves up a blasphemous delight in his convent-set Italian romp.

By Anton Bitel

Both film are now available as part of a special collector’s edition box set.

By Matt Thrift

The outspoken Dutch filmmaker discusses his triumphant return to cinema, Elle.