The plots of Clint Eastwood’s Play Misty for Me, Edward Bianchi’s The Fan and Eckhart Schmidt’s similarly titled Der Fan may already have revolved around obsessive stalkers – but it was Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction which, in 1987, updated this erotomanic theme right into the upwardly mobile aspirations of the Reagan era.

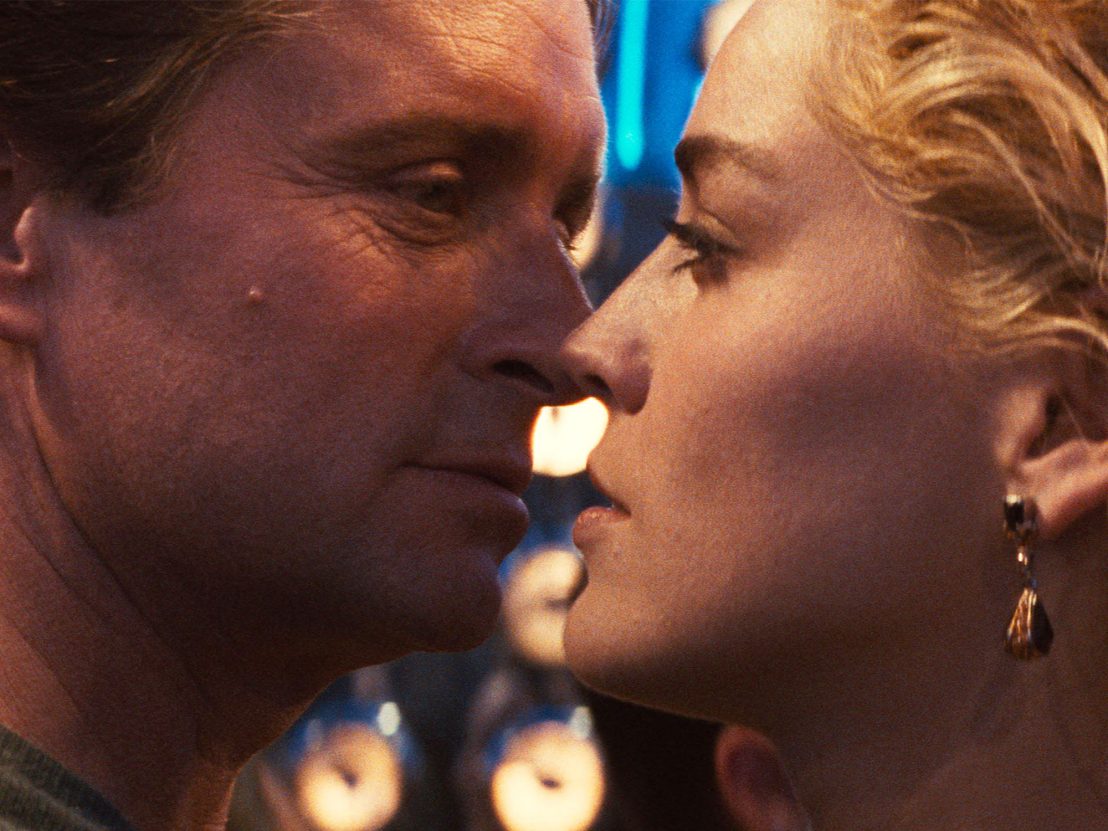

After straying with a weekend fling from the security of his marriage and family, a successful, affluent New York lawyer (Michael Douglas) discovers the precarity of his middle-class existence as his lover (Glenn Close), now spurned, simply will not let go, bringing a hell of grievous bunny-boiling consequences. Only after the (wronged) female lover has been coded as a psychopath and killed can the male protagonist return to the comfort of his bourgeois life, in what constituted a deeply conservative restoration of patriarchal values.

Fatal Attraction established a template for the erotic thriller which would peak in 1992 with similarly plotted films like Katt Shea’s Poison Ivy, Barbet Schroeder’s Single White Female and Curtis Hanson’s The Hand That Rocks the Cradle. In the same year, Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear, though a remake of J Lee Thompson’s film from 1962, adhered closely to the subgenre’s now routine formula while featuring a male stalker.

Yet no film was more subversive of this story type than Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct. Also made in 1992, it would turn the gendered tropes of Fatal Attraction on their head and bring them full circle, with the recasting of Douglas as the male lead marking the specific differences as much as the generic similarities.

Basic Instinct is perhaps most remembered for its frank softcore sexual content, emblematised by the iconic, often parodied (and even more often rewound and freeze-framed) scene in which its femme fatale Catherine Tramell (Sharon Stone) uncrosses her legs to flash her vulva both to the policemen interviewing her and to an audience not used to seeing such explicit imagery in a mainstream film.

Yet what is particularly striking about this sequence is not the (Hollywood) taboo of briefly exposed vagina, but the power afforded to Catherine – a woman who, without ever so much as leaving her chair, runs rings around the five experienced male police officers interrogating her. As verbally dextrous as she is physically seductive, Catherine is always in control, never allowing herself to be remotely rattled by the men’s barrage of good cop/bad cop questions, and running the session like a striptease in which she plays upon her male audience’s urges and weaknesses to distract them from what is important and to get exactly what she wants.

Catherine has fallen under suspicion of murder after her lover, the ex-rocker Johnny Boz (Bill Cable), is found in his cum-stained bed with multiple stab wounds from an ice pick. Her latest novel details a very similar murder, suggesting either that she, or an obsessive reader, is the killer – and as Detective Nick Curran (Douglas) investigates, we quickly notice that he is in every respect outclassed by his quarry, a multi-millionaire heiress with a Berkeley degree in literature and psychology (magna cum laude) who is much smarter and infinitely richer than her pursuer, and altogether defter at the psychosexual game-playing in which they will both soon be engaging together.

Nick may imagine that he is a match for this bisexual, erotically omnivorous libertine, he may think that his own questionable history of suspicious ‘accidental’ shootings on the job makes him as dangerous as any killer, and he may even suppose that he can nail and dominate and own Catherine in and out of bed, but really he never stands a chance against a grand mistress of manipulation. And so the film renders its male hero a pathetic, foolish figure, while its antiheroine manages the film’s convoluted scenario as skilfully as she plots her novels. Indeed, her next book – about a doomed policeman – is expressly modelled on Nick.

Even as we see Douglas retreading his old stamping grounds from TV’s The Streets of San Francisco, Verhoeven has permanently shifted the terrain, so that this homicide detective is slave to his addictions (drinking, smoking, sex), and figured all at once as a criminal, a rapist, and himself the obsessive stalker in this erotic thriller, while a powerful, pleasure-seeking woman calls all the shots and upsets the male order.

For where Nick fancies himself the protagonist, really he is just a character in Catherine’s story. And as he pursues her through the streets and in the sheets, she is always in the pole position, leading Nick on a merry chase along a route of her own making. Catherine likes to cultivate a coterie of past killers – including her girlfriend Roxy (Leilani Sarelle), her friend Hazel Dobkins (Dorothy Malone) and even Nick himself – for the intoxicatingly chaotic edge that they lend her life, and the inspiration that they bring to her fiction. Yet in this world of psychopaths and ice-cold killers, Catherine is always not only on top, but several steps ahead.

Basic Instinct features a second interrogation scene, this time with Nick himself rather than Catherine in the hot seat, after a colleague with whom he had recently had a public confrontation is found dead. Nick repeats verbatim lines that Catherine had uttered in her own interview, but like an inferior understudy, he fails to deliver them with the same strength and conviction – and has to be rescued by an intervention from his sometime girlfriend, police psychologist Dr Beth Garner (Jeanne Tripplehorn), to avoid a fate worse than merely being suspended on ‘psycho leave’.

“She’s as crazy as you are,” Nick’s boss Lieutenant Phillip Walker (Denis Arndt) had said earlier of Catherine. In fact she is crazier, and cooler. ‘Shooter’ Nicky’s confidence, his cockiness, the sorts of qualities that normally define cinema’s male heroes, amount to little – while it takes a woman who is handy with a phallic ice pick to outplay him effortlessly at every twist and turn.

The constant paralleling of this maverick cop and his prime suspect, always to Nick’s disadvantage, redresses the gendered imbalance found in films like Fatal Attraction (which empower their female leads only to demonise and destroy them). Here Catherine is given free rein to enjoy twirling Nick and others around her finger, to screw with Nick’s head (as much as with his body), and perhaps to get away with murder. Far from being defeated, she survives and triumphs, with Nick’s future, even his very life, left entirely in her wandering hands.

The result is a Hitchcockian thriller with the kink brought right to the surface, and with a woman very much in the driving seat. It is slick and glossy, but also tawdry and crass, and spawned copycat ripoffs whose sloppy seconds were even tawdrier and crasser. But Basic Instinct earns its status as what Nick deems “the fuck of the century”, or at least what Catherine grudgingly concedes to be “a pretty good beginning”, in radicalising the sexual politics of a subgenre more often associated with male privilege.

Basic Instinct is available in a 4K restoration as a Collector’s Edition UHD, a two-disc Blu-ray, a two-disc DVD, Steelbook and digital via StudioCanal from 14 June.

Published 14 Jun 2021

Events like Le Festival du Film de Fesses are exploring stigmatising and transgression on the big screen.

Jane Campion’s much maligned 2003 thriller offers a vital subversion of the male gaze.

By Anton Bitel

The 1980 coming-of-ager Spetters is one of the Dutch master’s most uncompromising and controversial works.