Although perhaps best known as the screenwriter of Martin Scorsese’s Oscar-winning 1976 film Taxi Driver, Paul Schrader has gone on to become a distinctive director in his own right since the late 1970s. Schrader’s third feature, 1980’s American Gigolo, is one of his most interesting and memorable. As his latest intoxicating effort, Dog Eat Dog, arrives in cinemas, it’s this earlier effort which seems most ripe for a revisit.

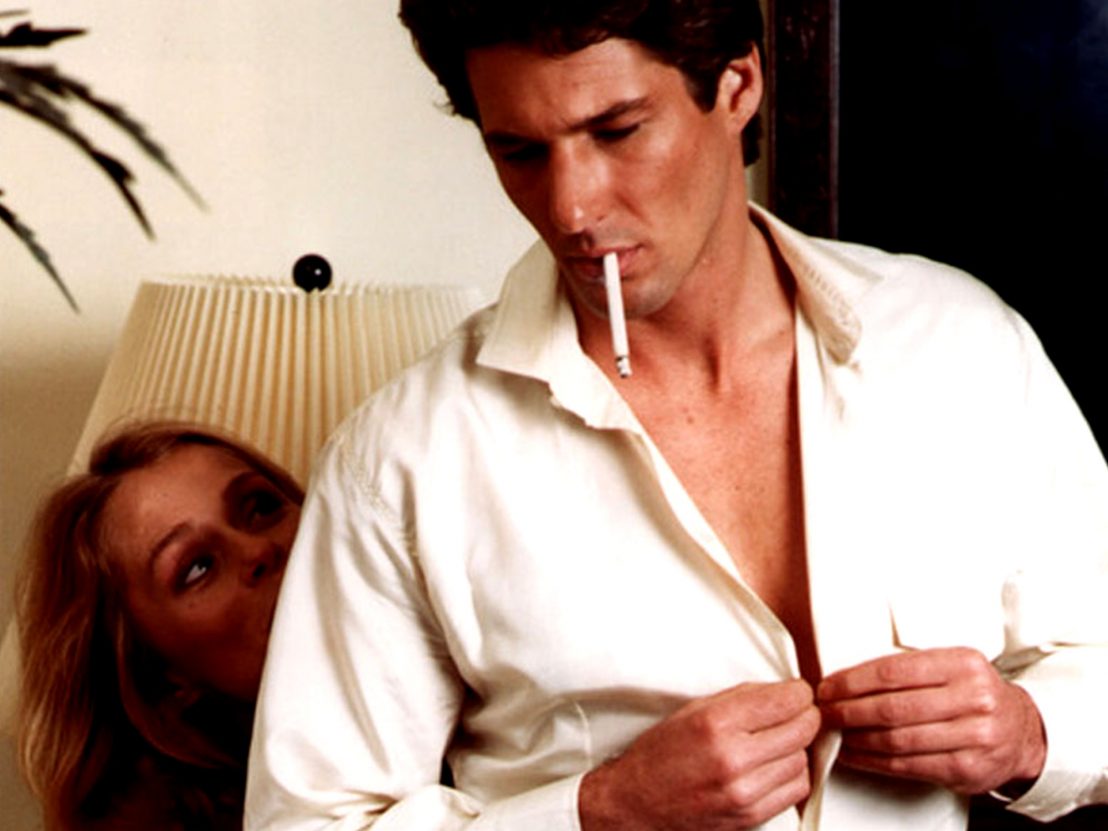

If nothing else, American Gigolo can take credit for introducing Hollywood and the world to two things: the luxury Italian fashion label Armani, and, after the taster of Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven two years previous, future megastar Richard Gere in all his glory. And what an introduction. Decades before Magic Mike, American Gigolo was busy unashamedly objectifying its straight, male lead. But unlike almost every female character in mainstream cinema, Gere’s Julian is a man who always actively participates in his own objectification.

Julian spends a lot of time taking care of his appearance and enjoys the attention that preparation brings. Considering the depressing debates that Instagram selfies still spark today, it is incredibly refreshing to see a film made 36 years ago which does not condemn male narcissism. Instead, it unabashedly salutes its protagonist with flattering close-ups and extended takes. For much of the film’s runtime there is simply nothing to do but watch Gere walk with the most obscenely sensuous gait, or sit with the coolest nonchalance.

He is always the best dressed man in the room for obvious reasons. Under the pretence of ‘guide or translator’ for rich, often much older women visiting Los Angeles, Julian sells much more than his company. The film establishes its risqué schtick early on in a scene where Julian almost gets annoyed at a new client – seemingly not used to this kind of service – and makes clear with the least subtle innuendos that he is ready to “open the champagne now.”

When Julian realises he is being framed for the murder of a client, the film seems to morph into a typical crime movie set in the world of sex and drugs. But American Gigolo is a pleasurably complex, double-sided film. The genre development is only a false-bottom, concealing an entirely different film. Within the cold LA crime thriller template echoed by both by the events in Julian’s life and by the film’s style (all cool neons, synthy score by Giorgio Moroder, and stylised action), one element stands out which contains the secret to the entire movie.

Lauren Hutton’s Michelle is a married woman Julian meets by mistake one evening. She falls in love with him almost immediately, and though her love is unreciprocated, this rejected ‘romantic interest’ regularly and stubbornly returns to interrupt the flow of the crime narrative. When she asks him, “where do you get your pleasure from?” the question sounds out of place and totally irrelevant to the fairly schematic plot. Julian’s lush lifestyle, his gorgeous features and his praiseworthy mission to give pleasure to women are undeniably attractive traits. They attach us to his perspective so strongly that, just like him, we completely fail to understand what Michelle really is all about until the very end of the film.

With all of the people he used to call his friends turning their back on him, Julian finds himself spiralling towards a showdown with the law. He realises, like we do, that his entire life relied on a handful of people who were on his side only as long as they stood to profit. His entire life was one big business transaction. In that moment, Michelle’s relevance becomes crystal clear.

Long before the crime plot was to lead Julian to lose all his friends, she had already realised that he was all alone; that he had already worked himself into a more metaphorical corner than a prison cell. Only then, after he has lost everything that had no value in the first instance, does Julian realise that love isn’t merely a distraction but something he had always needed. It’s a melancholy and poignant ending to a film that is rich with superficial pleasures.

Published 14 Nov 2016

By Matt Thrift

The veteran Hollywood maverick talks Dog Eat Dog, Scorsese and the challenges of modern moviemaking.

Is it possible for women to love movies which promote a regressive, misogynistic worldview?

By Simran Hans

Simran Hans considers the link between two of America’s most prominent and progressive leading men.