The Moonlight director discusses the value of film school and finding a personal voice.

It was 2008’s festival hit Medicine for Melancholy that put the name Barry Jenkins on the map of many perceptive cinephiles, but few could’ve predicted that he would make such a stellar return. Moonlight is his stunning, erotic triptych about a black Floridian man wrestling with his emotions across three generations, and is now one of the main 2017 award contenders.

LWLies: Do you have memories of going to the cinema with your mother?

Jenkins: Not with my mother but I do remember always liking movies. Even when I discovered there was a film programme at Florida State, the thing that I thought was, ‘Wow I’ve always really loved movies, I should check that out’. It’s kind of cliche because my films aren’t escapism. I don’t remember seeing any kids films. I remember going to see The Colour Purple, Aliens, Terminator 2. Really big and loud Hollywood films.

Why do you think you’ve ended up not making those kinds of movies?

When I first got into film I realised it was a great vehicle to express myself. But when I started film school I was in a small class of about 30 kids but everybody’s movies looked and sounded the same. And that’s because we all grew up watching the same things. It’s not like today when, if you have a hard drive, you can just shoot until you fill it up. We were very limited when it came to how much we were allowed to shoot. I didn’t know anything, I didn’t know you needed light to expose film. I also thought, I’m gonna watch the shit that nobody else is watching, and that was foreign cinema.

This idea of people going through that film school process together, you would expect to see different ideas and different types of storytelling.

You know, it’s weird. It wasn’t a melting pot of personalities, but again, the US dominates the film industry. Cinema is a global economy, a global art form. But the things that have the marketing money to really push above the noise are these huge Hollywood studio productions, some of which are good but most of which are not. But they’re not meant to be. I like to think your influences don’t dictate your aesthetic, but in this case, our influences were dictating our aesthetic. It was when Wes Anderson was becoming popular, and there were so many Wes Anderson knock offs at film school. And I was like, ‘I’m not gonna do this. I’ll find something else.’

What does American cinema look like to you?

To me American cinema is… different. I think in the US there’s a lot of energy and opportunity from a craft where people are extremely talented. I think there just has to be more diversity of thoughts to approach which story forms are worthy of funding and support but I think it’s a great time to be an American filmmaker because the tools have become so accessible and the avenues to get the work out have become so varied and expansive I think there’s a lot of opportunity. The problem is I don’t know that cinema is as important to public discourse as it was 10 years ago, 20 years ago certainly 30 years ago.

Why do you think that is?

You and I both have screens in our pockets that have a higher resolution than any TV you could have bought 10 years ago. There’s just so much more stimulus but opportunity. Cinema as an art form has just reached its century mark and a lot of stories have been told and, not that people are over it but people are very savvy so it’s very hard to create something they haven’t seen before or something they haven’t thought of before.

People are cynical as well.

People are very cynical. The world is on fire. So if you’re making a film and there’s not a quality to it that is a burning passion, a burning desire, then it’s not important.

The world is connected like never before, and it feels like people are more interested in different cultures and different modes of storytelling.

There is a hunger for it and I think there’s always been a hunger for it. There used to be like four cinema chains and three premium cable channels and it was all very concentrated. Now it’s so varied that there is literally more content sources than there is content to fill the space. I think what’s happened is voices in the past may not have fit into those four or five finite spaces. Now, if you don’t fit here you just go over there. The task now is is to find a production model that works if you don’t sell or play in a certain space. My first film cost $15000 on a camera that cost $4000 and if we tried to make the film four years prior it would have been impossible. People who come from where I come from don’t have access to the tools necessary to make a film. The voice is there. The story is there. But the means to tell it have always been beyond our reach and I think now the tools to make a quality film are much more attainable. These barriers to entry no longer exist.

Is it your job to think about the audience?

It is and it isn’t. I want to be considerate of the audience but I don’t want to make decisions that anticipate the reaction of an audience. The audience comes to the film to see what I feel, what the actors feel. I think the type of moviegoers I make films for don’t go to the movies expecting me to make things that they want. We’re putting out energy and the audience is responding to it. It shouldn’t go in reverse. We work in a very privileged artform. This shit is expensive. So if you’re not considering the audience in some way, if you antagonise the audience to a degree that is simply too far for them to get a foothold in the work, nobody’s going to come and see your film.

Nobody’s going to recommend your film to anyone else and you’re not going to get to make more films. Now is that fair to think of that when you’re creating a work of art? No. But making something that costs hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars, we can’t just burn that money. You have to make concessions so that people will be willing to watch and be interested in that piece. And to further that people will be motivated, incentivised and interested to pay to watch the piece because these things cost money to make.

What do you love about movies?

I love how movies make the world seem like a very small place. I was talking to a reporter the other day about the use of ‘Caetano Veloso’ in Moonlight. That’s an homage to Wong Kar-wai and Happy Together – a very overt homage I must say, but I wanted to be upfront and honest about how there’s this filmmaker working in Asia whose cinema I love and here I have my characters in inner city Miami and the emotions they feel are the same. Totally the same. These people will never ever meet and yet through this art, through cinema we can show how much alike they are. They’re a world apart but they’re so so close. That’s what I love about movies.

Published 11 Feb 2017

By Nick Chen

This San Fransisco-set drama from 2008 is the perfect primer for Barry Jenkins’ critically-acclaimed latest.

By Josh Lee

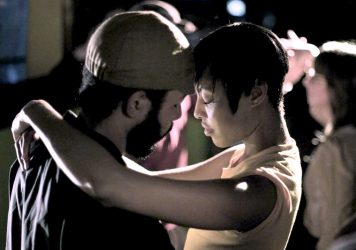

By not showing physical intimacy, Barry Jenkins allows sexuality to surface in his film in other ways.

Inspired by Todd Haynes’ Carol, explore our potted history of great films that depict gay lives on screen.