Moonlight is a meticulously crafted, brilliantly acted and sumptuously shot coming-of-age film about a young, black gay kid growing up in poverty in suburban Miami. As queer as it is black, Barry Jenkins’ film now finds itself teetering on the edge of becoming the first queer film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. But we only need to look back as far as Brokeback Mountain to see how heterosexual squeamishness can stop even the most accessible queer love stories in their tracks. Or Milk, which went some way to desexualise its title character and still missed out on Best Picture.

The compromises made by queer films in past attempts to break the Academy’s Best Picture glass closet haunt Moonlight. We don’t just want it to win. We want it to win in the right way, showing queerness as we recognise it. Not just love, but sex. And not forbidden, shadowy sex as seen in films like Brokeback Mountain. Having been shamed for centuries, gay culture is now dominated by sex-positivity, and we value frankness and confidence in our sex scenes. Increasingly we see it in television and films made with only us in mind, but when a feature sets its sights on mass appeal or awards glory, things tend to get a little timid.

With the sexual content of Moonlight amounting to a few awkward seconds of adolescent hand-jobbing, it’s easy to feel as though the film has exercised “cautiousness”, as the Guardian’s Guy Lodge put it in his recent analysis of the film, when it comes to portraying physical sex. There’s no disputing that Moonlight isn’t chock full of sex. But describing it as an exercise in coyness sells the film short. By transcending our sex lives, Moonlight makes room for an incredibly rich portrayal of what sexual identity is and means for queer men – specifically for black queer men who face expectations of hypermasculinty.

That specificity is important. Where hypermasculinity manifests, gay sex can be as dangerous as it is liberating. And let’s not forget that in America, one in two black queer men will contract HIV in their lifetimes. So there is a truthfulness in Chiron’s avoidance of sex, explained by the betrayal he faces at the hand of his first and only lover, schoolfriend Kevin, and the wider context of the intersecting oppressions faced by men like him in the real world.

That’s not to say closeted black men don’t have sex. More that the events which shape Chiron’s life – and the world he exists in – are complicated enough to build a character for whom sex is plausibly a risk worth avoiding, no matter how keen the urges. When Chiron reunites with Kevin as an adult and admits he never touched another man again after their encounter, it’s reasonable. Chiron isn’t being sanitised like Sean Penn’s Harvey Milk. There’s a logic to why Moonlight is sexless – and it’s all to do with the big picture.

By taking sex out of the equation, Jenkins allows queerness to surface in other ways. As the camera lingers over a young Chiron in the bath, queer viewers will recognise how he accepts the sadness of isolation in exchange for a moment’s peace from the hyper-vigilance he’s developed to survive. Later, when we meet Chiron as an adult, we recognise the hardened exterior he’s built to survive – many of us do the same in our jobs, with our families, and even with each other.

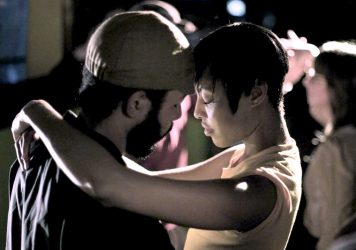

When he reunites with Kevin and that shell cracks, we recognise the relief he feels in the knowledge that he is safe to be his true self. Everybody gets a little lonely sometimes, but Chiron’s solitude is queer. We know it because we’ve lived it. For the privileged among us, it’s an exaggerated reflection our own experiences. For the less fortunate, it’s to-scale.

Queerness may not be articulated in obvious ways in Moonlight, but much of queerness isn’t really articulated at all in real life. What the film provides instead is arguably more important. By confronting us with queer childhood, we’re forced to consider what growing up queer in our heteronormative society robs us of: safety, opportunity, peace of mind, authenticity.

Moonlight is a study of aspects of queerness we sometimes find too painful to talk about, because they demand that we accept that many of us were forced to swap the naiveté of “normal” childhood for constant awareness of our surroundings and any potential threats. Confronting this through Moonlight gives queer audiences the chance to reconcile feelings of loss and resentment towards our childhoods, and begin healing in a way that no sex scene could.

If Moonlight manages to make history and take home the Best Picture Oscar, it might have something to do with its lack of onscreen sex. But that doesn’t make it a film of compromises. Moonlight works a study of how masculine heteronormativity can break us down and rebuild us in its own repressed, damaging image. That’s a far more urgent conversation than sexual expression.

Published 11 Feb 2017

Inspired by Todd Haynes’ Carol, explore our potted history of great films that depict gay lives on screen.

The Moonlight director discusses the value of film school and finding a personal voice.

By Nick Chen

This San Fransisco-set drama from 2008 is the perfect primer for Barry Jenkins’ critically-acclaimed latest.