Paul Thomas Anderson’s spiritual post-war love story will restore your faith in cinema.

A swirl of ocean water. The cold touch of Navy steel. A thousand-yard stare set beneath the bullet-dimpled contours of a Brodie helmet. Within the opening frames of The Master, the ticker-tape euphoria of the Allied victory is offset by the painful truth that for some men World War Two never really ended. Of the countless young soldiers that were struck down by some form of psychological trauma, only the most acute cases were successfully treated by experimental therapies such as hypnosis and narcosynthesis. For others, the horrors of war remained indelibly fresh.

Waiting out the last days of the war on the champagne sands of an unidentified island in the South Pacific, Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix) first appears more beast than man. Shirtless and dishevelled like some battle-weary Robinson Crusoe, we watch him hack away at coconuts with a blunt machete and wrestle his Navy buddies on the shore. He is a harrowing picture of post-traumatic stress disorder; his sunken eyes (bloodshot from an addiction to crude liquor picked up during his tour) deep pools of anguish, his wiry frame twisted and stiff from years of front-line action. He is both literally and metaphorically at sea. A tragic addition to writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson’s crowded roster of lost souls.

Back on home soil, Freddie is told by his superiors that the responsibilities of peacetime rest on his shoulders. He can become a chicken farmer, grocery clerk or department store photographer, return to education or start a family. It doesn’t really matter. The Golden Age of American Capitalism is dawning and happiness is assured to those who are willing to reach out and grab it. But Freddie is precariously out of step with the newly galvanised civilian population, his psychosocial adjustment fraught with antisocial outbursts and irrepressible carnal urges. He prowls the shadows of society looking for a quick fix (and a quick fuck) wherever he can get it. He is savage and insatiable.

One inebriated evening Freddie boards a private yacht, the Alethia, lured by bright lights and the sounds of revelry spilling from the deck. The next morning he is summoned to the captain’s chambers like a stowaway. It’s here that Freddie is formally introduced to Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a robust, well-groomed man dressed in a regal nightshirt and bathed in a soft, exalting light. Apparently struck with an overwhelming sense of déjà vu, Dodd embraces Freddie with curious affection, alluding to a prior meeting between them – not from the night before (which we know to be their first meeting even though, crucially, we never see it) but some other indistinct point in time. Perhaps a past life. Dodd asserts that he is a writer, doctor, nuclear physicist and theoretical philosopher, and that he and Freddie are both “hopelessly inquisitive” men, an assessment that greatly amuses his guest.

In philosophy, ‘alethia’ refers to the understanding of truth, something that is evident or fully disclosed. In christening Dodd’s vessel accordingly, Anderson subliminally evokes the underlying principle of The Cause, a mysterious religious science group founded by Dodd on his own abstract ideology. Teasingly, there is no evidence pertaining to Dodd’s self-professed list of accomplishments, and yet Philip Seymour Hoffman’s performance is so commanding that we immediately accept Dodd for who he is (that is, everything he claims to be). Although later we will come to view him as a compelling public speaker, a self-styled philanthropist, a conman and a charlatan, for now, deep in the bowels of the Alethia, he appears unreservedly sincere, someone to be trusted. Like Freddie, we quickly fall under his spell.

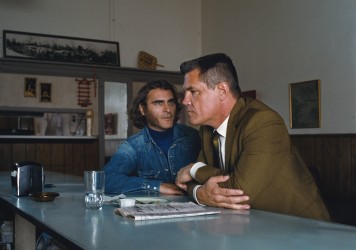

In the film’s standout scene, which brings to mind the opening diner table exchange between Philip Baker Hall and John C Reilly in Anderson’s 1996 debut Hard Eight, Freddie agrees to participate in a one-on-one counselling-cum-conditioning exercise that Dodd has coined ‘processing’. With a tape recorder rolling, Dodd instructs Freddie to respond without hesitating or blinking, and proceeds to rattle off a sequence of probing and repetitive questions: Are you thoughtless in your remarks? Do your past failures bother you? Have you ever had sexual contact with a member of your family?

What begins as an informal profiling session – filmed as a breathless single-shot close-up – quickly escalates into something more sinister. Dodd’s fascination with Freddie congeals into raw obsession as he mercilessly peels back the layers of his subject’s psyche. Amid revelations of a recurring dream about his mother and a deep-seeded resentment towards his estranged father, it becomes apparent that, while his malaise was compounded by his time at war, Freddie’s condition could well be rooted in an earlier trauma. In this moment a prescient question arises: is it possible to break what is already broken?

Freddie is told that he has wandered from the proper path and is asked to look “back beyond” to return to the pre-birth era. Dodd knows that before him sits not just a worthy benefactor of The Cause but a righthand man in waiting, someone who might substantiate his bold theories. But Freddie is more interested in his own self-medicating hipflask than Dodd’s peculiar self-help tonics. The big idea of The Cause is that salvation comes from returning man to his inherent state of perfection, a hypothesis that provokes adulation and scepticism in equal measure. As one outspoken cynic eloquently observes during one of Dodd’s healing sessions, science based on the will of one man is the basis of cult.

This is the only time you’ll hear the ‘c’ word in The Master. Anderson isn’t interested in drawing parallels between The Cause and any real-life quasi-religious group. Rather, he uses the concept of fanaticism as a springboard into a broader evaluation of pacifism versus radicalism, good versus evil, and truth versus fiction. Onto this dense thematic framework he weaves numerous motifs from his previous five features: the dysfunctional family, the surrogate father, the sexually domineering male.

Freddie’s over-active libido, for instance, is exposed somewhat surreally during a dinner party scene in which he mentally denudes every female guest, as well as during a Rorschach test at the Naval debriefing base and in flashbacks to that champagne beach where Freddie aggressively dry humps (in the most literal sense) a voluptuous figure sculpted out of sand. Anderson has spoken of a fixation with pornography that developed in his early teens, a vice that would manifest itself in his 1988 debut short, The Dirk Diggler Story, and Boogie Nights, the 1997 feature it inspired. Like Dodd, Anderson neither victimises nor condemns Freddie but instead views him as a kind of animal, someone who can only hope to vanquish his demons once his primitive impulses have been suppressed.

To Dodd, Freddie is part pet project, part prodigal son – a dedicated understudy who is prepared to sacrifice himself for The Cause even though we suspect he doesn’t fully understand why. He serves Dodd with unwavering loyalty, clashing with police at the home of a benefactor when Dodd is arrested for embezzlement, showing no regard for his personal welfare. This recklessness makes Dodd’s family – demure matriarch Peggy (a sparingly used but sensational Amy Adams) and biological kids Val (Jesse Plemons) and Elizabeth (Ambyr Childers) – increasingly wary of The Cause’s disruptive new recruit. Freddie feeds and facilitates Dodd’s monomania, inspiring something in him that no one, not even his wife, can explain. Understandably Peggy feels threatened by Freddie, but she tolerates his volcanic personality because she loves her husband too much to jeopardise his newfound creative momentum.

If all this identifies The Master as an intimate character study, really it is so much more than that. It’s a stark and at times unsettling study of the human condition as seen through the eyes of two enigmatic individuals both stepping to their own beat at a time when social conservatism was becoming increasingly prevalent. America in the 1950s may have been a land of prosperity and opportunity, but this was also a decade in which the fear of communism and the persistent threat of nuclear conflict weighed heavy on the public consciousness.

This polarised mood is reflected in both Jonny Greenwood’s fretful jazz-infused score and Mihai Malaimare Jr’s dreamily textured 70mm palette. Filling in for Anderson’s regular DoP Robert Elswit (who was busy filming The Bourne Legacy at the time of production), Malaimare Jr manages to accentuate every meticulous period detail without ever distracting from the metaphorical nuances in Anderson’s script.

Like Daniel Plainview before him, Dodd is presented as a principled family man. But above all he is a man of bulletproof conviction, someone self-assured and arrogant enough to stand behind his ideas however unusual and implausible they might be. America was built by men like Dodd, by the dreamers and pioneers whose feats captured the public’s imagination and transformed a young nation ravaged by civil war into an economic and technological superpower. Of course, The Cause is a means to Dodd’s own financial and hubristic ends and not an altruistic investment in his countrymen or species at large. Yet whatever his motives, it’s clear that Dodd is not about to let anything or anyone stand in the way of his pursuit of greatness.

Fluid long takes and elaborate Steadicam tracking shots are recognised hallmarks of Anderson’s work, yet in The Master it is the protagonists themselves that are noticeably restless. We know that both men relish the sting of salt water in their lungs, but while Freddie drifts along in search of steadier footing, Dodd’s nomadic migratory pattern – he travels from San Francisco to New York City via the Panama Canal before eventually upping sticks to England – is by turns the result of his disdain for the white picket fence idealism of this mid-century boom and an occupational hazard of his conflict-ridden crusade. While initially this shared disconnect from the land strengthens Freddie and Dodd’s bond, it’s not long before their tacit kinship comes unstuck.

Freddie accompanies Dodd to the desert to retrieve a buried trunk containing Dodd’s unpublished work, which is bound in print under the title ‘The Split Saber’ and suffixed, ‘A gift to Homo sapiens’. At the book’s launch, Laura Dern’s hitherto devout believer picks up on a subtle terminological inconsistency, prompting Dodd to uncharacteristically lose his cool. We know he’s just making it all up as he goes along – his philosophy deals in trillenia and advocates time travel as a rational passage to spiritual enlightenment – but for the first time the mask slips and Freddie begins to challenge his master’s voice.

In an attempt to reaffirm Freddie’s faith, Dodd takes him back into the desert. Driving into the middle of nowhere, Dodd picks a point on the horizon and races towards it on his motorcycle before returning to his starting position. It’s a typically absurd stunt, the kind of pseudo-theory Dodd is used to seeing Freddie lap up. Not this time. Freddie floors it and doesn’t look back, leaving a crestfallen Dodd to traipse across the desert in embittered contemplation. After going their separate ways, Freddie and Dodd reunite in England at The Cause’s lavish new headquarters. Freddie had been expecting to be welcomed with open arms, and is visibly upset when Dodd, with Peggy at his side, acts indifferently towards him.

Just as Burt Reynolds’ Jack Horner reached the end of his tether with Dirk Diggler in Boogie Nights, so Dodd has come to accept the fact he will never be able to muzzle Freddie, let alone mould him in his image. But Dodd’s aloofness carries another meaning. He has felt the pain of having his heart broken by Freddie before, and though he yearns for his adopted son to reassume his place at the head of the flock, he knows he couldn’t bear to watch him ride off over the horizon again.

Freddie may be emotionally stunted, but does that automatically make him more susceptible to being manipulated by a charismatic shaman like Dodd? If the generalisation that the world is divided into those who lead and those who choose to be led is to be believed, is it also true that, as Dodd points out, “Every one of us is living for some master”? Are human beings simply hardwired to conform? Or are we all searching for a higher truth? These are the types of questions that make The Master so compelling – not because there are no straight or easy answers but because Anderson leaves so much open to interpretation.

This is a film that will affect different people in different ways. It is in many respects a sad portrayal of doomed companionship, although there is a warm glow to Freddie and Dodd’s brief honeymoon period, as well as a flashback to a tender scene between Freddie and his sweetheart, to whom he promises his hand only to discover upon returning home from war that she has already accepted another man’s proposal and skipped town. There are unexpected bursts of humour, too. There’s even a fart gag.

Make no mistake though; this is serious, high-emotion filmmaking. And yet for all that The Master is fragranced with gracenotes of Herman Melville’s ‘Moby Dick’ – which it echoes in its use of stylised prose and symbolism to explore complex themes such as class, duality and the existence of a supreme being – and to a lesser extent Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, stylistic idiosyncrasy and magical realism remain vital components of Anderson’s storytelling fabric.

The Master’s lack of operatic catharsis (there’s no Old Testament crescendo or bloody third-act coming to blows) might suggest that Anderson has sated his appetite for composing grandiose metaphysical parables. In truth, however, there is simply no call for such dramatic excess here. Towering performances aside, it’s the understated gestures that stick with you – be it a gentle death knell in the form of a song and a single tear, or a cut away to a naked sand woman that emphasises the importance of holding on to the things you love.

Published 2 Nov 2012

Any new film by Paul Thomas Anderson is a major cinematic event.

Confounding and intoxicating. A technically flawless work of oceanic depth that hits you in waves of emotional resonance.

All hail the master.

Paul Thomas Anderson charts the end of the hippy dream in this blissful gumshoe chimera.

The star of Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master discusses his special relationship with his long-time friend and collaborator.

What Jonny Greenwood did on his holidays makes for rousing cinematic statement.