A jaw-dropping spectacle and brain-melting existential nightmare, Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam opus is touched by genius.

If the first casualty of war is truth, Apocalypse Now must be the greatest lie ever told. Because here, in the journey of a Marine captain through the dark heart of Vietnam, Francis Ford Coppola has captured the full spectrum of war – its horror, madness and grotesque, cosmic absurdity. But in doing so, he embarked on a parallel journey – a ruinous, cathartic expedition both physical and spiritual. Pushed to the limits of his own ambition, he refashioned his film into something closer to poetry than fiction, and conferred on Apocalypse Now its own awful, irresistible truth.

That truth is less about the events of the war itself (though they are recreated with stunning authenticity) than the madness at the heart of human nature. If Apocalypse Now appears to pre-empt many of the Vietnam movies that followed – distilling into a single film the action spectacle of Platoon, the psychological drama of The Deer Hunter and the moral ambivalence of Full Metal Jacket – it is because at the time, Coppola imagined it would be the only American film to deal with the war. It fell to him, or so he thought, to make sense of Vietnam.

For inspiration, he reached beyond the war to something more fundamental, finding it in ‘Heart of Darkness’, Joseph Conrad’s account of colonisation in the Belgian Congo, first published in 1899. Here, in the character of Kurtz the ivory trader, Conrad created a symbol of the west’s destructive greed and cruelty. To Coppola, who reimagines him as a renegade Colonel, he is even more complex.

Brando’s Kurtz shows us what lies beyond the limits of human behaviour. Evil, certainly, but also a kind of terrible clarity. In the face of madness, the only sane response is insanity. Kurtz, in his viciousness and savagery, has achieved enlightenment. He has set himself free.

Shot in the Philippines between 1976 and ’77, with post-production stretching into 1978, Apocalypse Now, still unfinished, received its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in 1979, where it shared the Palme d’Or with Volker Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum. For Coppola, it was the culmination of a journey steeped in madness and mythology, as arduous and transformative in its own way as the events he set out to capture on camera.

His experience in the Philippines wrote itself into Hollywood legend. How the budget, originally set at $14 million, doubled after a calamitous shoot, with Coppola personally liable for the overage. How Pacino, McQueen and James Caan all passed on the role of Willard. How Harvey Keitel was hired then fired. How Brando was paid $3 million and turned up overweight and unprepared. How the Philippine government lent Coppola helicopters and pilots, only to demand them back to attack rebel forces. How a typhoon destroyed the set. How Coppola struggled with the ending. How he lost himself in the jungle. How he never really came back.

But what’s striking about watching the film through new eyes on the big screen – restored and re-mastered by Zoetrope Studios – is how none of that really matters once the lights go down and ‘The End’ strikes up over a backdrop of thudding choppers and psychedelic smoke. It’s not nostalgia that drives Apocalypse Now, it’s the dawning thrill that this is a movie that matters in the here and now of new conflicts and old lies. “Some day, this war’s gonna end,” says Robert Duvall’s Captain Killgore. But it didn’t end, it just moved on. Kurtz survives – maybe not in a jungle, but somewhere, in a military geared to fight forever wars against abstractions and ideas. Apocalypse now, yesterday and tomorrow, for sure.

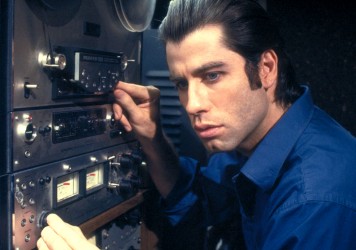

Martin Sheen plays Captain Willard, a US Marine assassin recruited to find and kill Colonel Walter Kurtz, former star officer, now AWOL, commanding a private militia somewhere in Cambodia. The local tribes worship him as a god. On his orders, they have executed three South Vietnamese army officers suspected of being double agents.

Kurtz, Willard is told by the top brass over shellfish and chilled wine, has passed beyond the bounds of acceptable human conduct. He is told about power, morality and ideals. Rationality and irrationality. Military necessity. It is the politician’s litany of hypocrisy. The truth is both simpler and more complex: “He kept winning it his way,” observes Willard as he begins to understand both the mission and his target.

The film’s narrative thread is provided by the Meekong River, the artery running through the centre of the war. For extended sections, Apocalypse Now assumes the trappings of a road movie, as Willard and the crew of his Navy patrol boat bear witness to the carnival tragedy of Vietnam. The further they progress, the more episodic and disjointed the film becomes. The effect is to foreground the mystical nature of Willard’s journey, and reposition the Meekong from narrative thread to a brittle mooring of consciousness, morality and civilisation, all of which are inexorably loosened as they approach Kurtz’s compound.

Discursive as it may be, Apocalypse Now contains unforgettable moments of drama. Most famous is the Air Cavalry assault on a Vietnamese village to a soundtrack of Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries’. But what’s striking about this scene and, later, the Do Long Bridge (‘asshole of the world’), isn’t the sound and fury, the chaos, or even jaw-dropping expense. It’s the control, the precision, the subtle layering of images.

Coppola’s mastery of the frame is absolute. When Willard lands in the wreckage of the village that Killgore and his men have recently annihilated, the camera stays on his face, curiously impassive as the scale of the carnage is revealed at the edges of the screen. Dead villagers, drifting smoke, rogue explosions, a confusion of noise, culminating in the startling image of a cow being airlifted to safety – all these elements accrete, one by one, until you lose yourself in the overwhelming whole.

There’s a tension here between ‘cinemaness’ and ‘realness’. In Killgore’s chopper assault, the strains of music and the multi-camera orchestration are pure cinematic spectacle. But what really gets the blood pumping in your ears isn’t Wagner, it’s the sound of the engine whine as the choppers scream over the bay. What moves you is the authenticity.

In these moments, Apocalypse Now shows its age – but gloriously, harking back to an era when you could believe your eyes. When films possessed that unmistakable aura of realness and danger. CGI may have opened up new possibilities, but it has robbed future generations of experiences like this one. And yet, even as it progresses, Apocalypse Now untethers itself from the real to explore the mystic, poetic nature of Willard’s confrontation with Kurtz – and himself.

Coppola struggled with the ending for months – he had come to embody both of his protagonists, consumed by their transformations and breakdown. In its final moments, the film reaches a kind of apogee, as if the last thread of reason and intellect holding it together has snapped, and all that is left is pure, primal power. For Coppola, it represented an artistic breakthrough, but in a more profound sense, Apocalypse Now marked the end of an era. There was nothing left after this. His relationship with the film industry would never be the same. Forget the awards, the hyperbole, the reviews. He had, like Kurtz, passed beyond judgment.

More than anything, the re-release of Apocalypse Now puts these last three decades into perspective. This is the film that took everything Coppola had to give – financially, physically, spiritually and emotionally. It cost him his marriage, his independence and almost his mind. But unlike the war whose truths he so painfully illuminated, his suffering served a noble purpose. Coppola made a friend of horror in the jungle, and it repaid him with something astonishing.

Published 22 May 2011

By reputation the greatest war movie ever made and one of the defining films of 1970s Hollywood.

A jaw-dropping spectacle and brain-melting existential nightmare. Apocalypse Now is touched by genius.

A gilt-edged, no-messing, accept-no-substitutes masterpiece.

Francis Ford Coppola’s magnum opus gets a big screen outing, see it if only to be able to understand The Simpsons better.

Francis Ford Coppola caused an unprecedented stir when he unveiled his unfinished Vietnam opus in 1979.

By Taylor Burns

Brian De Palma’s taut Watergate-era thriller highlights the difference between what a country believes itself to be, and what it actually is.