Movies and stories are everywhere in the beguiling new film by Iranian director Jafar Panahi.

In 2016, the great Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami died of complications resulting from what should have been a routine operation. This new film from compatriot and creative brother-in-arms, Jafar Panahi, appears as a gentle homage to the fallen master, a study of rural landscapes which picks away at the mythos and illusion of cinema. And in line with the director’s recent work (produced while undergoing an enforced travel ban), this film is also a hymn to the irrepressibility of screen storytelling, reminding us that recorded images of all variety take on new contexts depending on who’s screening them and who’s watching them.

The actress Behnaz Jafari, with her cherry-red crop of hair, plays a version of herself in this deceptively simple road movie. She’s supposed to be on set for a shoot, but has taken leave to drive through the night, with Panahi acting as her guide and chauffeur. She’s receives a video message from a teenager who has reached out in a moment of desperation. A rambling, teary-eyed plea becomes what appears like a filmed suicide, as she hangs herself from a small branch while hidden away in a cave.

It’s uncertain as to whether she followed through with the scheme, as her smartphone drops the ground at the crucial moment. So our intrepid travels dash to the scene with the purpose of finding out whether the girl did take her own life, and if she did, who then sent the video?

There’s much in-car bickering as our crack twosome head to the hills for what they believe to be a socially-conscious sleuthing mission. Yet Panahi is careful to keep his and Jafari’s motivations ambiguous, as their response to this cry for help sometimes seems as if it’s an earnest act of bourgeois responsibility, and others just a thing that anyone would do in this potentially tragic situation. In keeping with the director’s ambling style, this has none of the urgency of a crime film, and the most the pair do to hurry things along is reject the many offers of tea from the kindly locals.

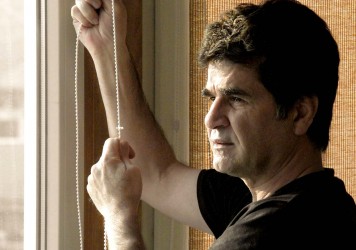

In films like Taxi Tehran and This is Not a Film, Panahi often presents himself as a man of the people, and it’s clear that he’s able to strike up an easy rapport with just about anyone he meets. This is perhaps why he’s able to coax such naturalistic and relaxed performances from his non-professional cast members. Yet here, he frames himself as a little more closed-off and reticent, often choosing to remain in his jeep as Jafari does the heavy lifting, or constantly claiming to be in a hurry and needing to leave. In the end, it does come across as a gently critical self portrait, a film about a man who has made a film without necessarily wanting to make one. Sometimes, a filmmaker just can’t help himself.

Elsewhere, the mystery leads to a documentary-like rumination on village life and the insidious suppression of women in Iranian society. Film becomes the connective tissue between cultures and a stealthy mode of communication, yet there are limits as there will always be an unbreachable divide between how different people live their lives and the systems they create within their own social microcosms. It’s not necessarily one of the director’s most easily lovable films, but it’s certainly one of his most enigmatic and thought-provoking.

Published 14 May 2018

This lyrical, on-the-fly road movie about the cinematic and poetic value of daily existence is a must see.

By Sarah Jilani

Despite facing severe restrictions Iran’s most important filmmakers continue to give its people a voice.

Jafar Panahi’s extraordinary self-portrait/protest piece is the gift that keeps on giving.