Mario Bava is among the most important figures in both Italian cinema and genre filmmaking. And yet you’ll rarely find him mentioned in the same breath as Antonioni, Fellini, Pasolini, Visconti or other greats of 1960s and ’70s. Bava achieved considerable critical acclaim in his lifetime and has since cultivated a major cult following. His work across a range of often ground-breaking and trend-setting subgenres is packed with an elegance and creative verve, transcending schlocky material, stingy budgets and sometimes atrocious re-editing by international distributors. Even when his films were butchered by censors or re-edited for drive-in audiences and grindhouse theatres, their merits and qualities still shone through.

Bava was a ‘mend and make do’ kind of guy – less an artist, more magician by necessity. Years of training at Rome’s Istituto LUCE, in just about every facet of the picture business, allowed him to craft ingenious solutions to pernickety issues on set, whether due to budgetary limitations or poorly written scripts. Dario Argento, John Carpenter, Nicolas Winding Refn, Martin Scorsese, Tim Burton, Joe Dante, John Landis, Francis Ford Coppola, Roger Corman and Quentin Tarantino are just some prominent members of the Mario Bava Fan Club. Ryan Gosling even went so far as to cast Barbara Steele, star of the incredible Black Sunday from 1960, Bava’s officially credited debut, in his 2015 directorial debut, Lost River. Like Bava, Gosling let her iconic face do all the talking.

Argento might be the father of giallo cinema, but it’s Bava who laid the ground work with his 1963 film The Girl Who Knew Too Much and 1964’s Blood and Black Lace, traces of which can even be found in Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon. Refn recently co-financed a digital 4k restoration of 1965’s Planet of the Vampires, presented in the Cannes Classics strand at this year’s festival. Why would anyone spend so much time and money on a film many dismiss as corny trash? While it definitely qualifies as such, the film had a sizeable impact on science-fiction cinema. Putting gothic horror into a spacesuit and blasting it off into the depths of outer space, Planet of the Vampires paved the way for everything from Alien to Event Horizon and beyond.

The Neon Demon clearly bears the influence of several Bava flicks. Though officially credited to Riccardo Freda, 1957’s The Vampires is a Bava film in all but name. As cinematographer he completed filming after Freda walked off set, shot new scenes and restructured virtually the entire plot. Both spring from the legend of Countess Elizabeth Bathory and how beauty, vanity and fear can lead to psychological derangement and murder. Blood and Black Lace – a proto-slasher bursting with primary colours set in the fashion world – is another movie Refn almost certainly watched and took notes on.

Bava was a master stylist with a taste for dreamlike atmospheres, memorable compositions and delicious colour photography bursting from the screen with a pop art, comic-book vibrancy. That’s the main reason he’s been praised by Martin Scorsese: for his ability to create pure cinematic images and moods. Ones that left an indelible impression. Scorsese remembered 1966’s Kill Baby, Kill when making The Last Temptation of Christ. The use of a ghostly young girl as a manifestation of evil was lifted from Bava’s gothic masterpiece.

Francis Ford Coppola 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula could have been retitled ‘Mario Bava’s Dracula’, for Coppola and his son, Roman, who worked on the film as a second unit director and was in charge overseeing special effects, were so taken with one scene in Black Sunday – a slow motion horse-drawn carriage riding through fog – they lifted it wholesale for Dracula’s arrival at the Borgo Pass. That scene simply screams Bava; with its use of in-camera effects, miniatures and glass plate trickery, Coppola made his grand baroque literary adaptation in the spirit of the Italian maestro.

Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction are profoundly indebted to Bava. Referencing direct shots from movies he loves is an unmistakable Tarantino traits, and there are several purloined from 1974’s Rabid Dogs. But it’s also to be gleaned in the dog-eat-dog nihilism, sweaty photography and a story unfolding over a matter of hours in the aftermath of a crime. And when deciding upon his follow-up to Reservoir Dogs, Tarantino decided to make the gangster picture version of 1963’s triptych of terror, Black Sabbath.

Published 30 Jun 2016

Iconic stars like Anita Strindberg and Edwige Fenech are the thread that ties this deviant subgenre together.

With The Neon Demon the Danish writer/director has made his most provocative film yet. We travelled to Copenhagen to meet him.

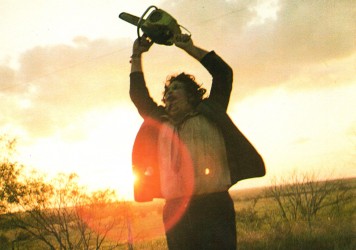

It may not be the most iconic piece of film music, but Tobe Hooper’s organic, visceral soundtrack is uniquely unsettling.