Think of a canonical horror film, and what will most likely spring to mind is a particular piece of music. The threatening two-note motif in Jaws embodies the terrifying presence of the deadly shark more even than the sparsely-used mechanical models; a combination of synths and piano brings a pervading sense of menace to a quiet suburb of Illinois in Halloween; the shower scene and other violent moments in Psycho would be nowhere near as effective were it not for the piercing, dissonant strings that accompany them; and Mike Oldfield’s haunting ‘Tubular Bells’ has become synonymous with pea soup.

But what about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre? Its score, a low-budget, experimental work constructed by director Tobe Hooper and his musical aide Wayne Bell, comprises a complex layering of percussive, organic and electronic sounds to create a chilling, unsettling ambiance. It’s garnered praise over the years, but has never come close to being absorbed into popular culture like the examples listed above. It lacks their tuneful catchiness – you won’t find yourself irresistibly humming it to yourself days later. The emphasis is instead on subtly shaping the atmosphere, and of provoking a feeling of dread and disorientation that washes over the audience despite often barely even noticing its presence.

This music alone is enough to unnerve anyone, but it’s the use of sound emitted from on-screen objects and characters that really defines the sonic landscape of the film. For all the bizarre behaviour of its characters, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre has a naturalistic tone, with scares largely produced by natural, practical sound effects – the screams of its heroine, Sally (Marilyn Burns), and the thunderous roar of Leatherface’s (Gunnar Hansen) chainsaw.

The chainsaw makes its first appearance during the killing of the film’s other female character, Pam (Teri McMinn). Whereas two of the three male characters are abruptly killed-off within a matter of seconds after encountering Leatherface via fatal blows from a hammer, her attack is lingered upon, as she is briefly permitted to run away screaming before being caught, while the butcher on this occasion takes his time and indulges in several revs of the chainsaw. The two noises combine to create a deafening, horrible wall of sound that the film will return to again and again later on.

But it’s Sally’s blood-curdling screams that live longest in the memory. From the moment she witnesses her wheelchair-bound brother being slaughtered (the only male character to die at the hands of the chainsaw, but whose own screams aren’t given the same prominence as his onlooking sister), the entire third act boils down to a straightforward pursuit as Sally attempts to escape Leatherface and his equally twisted family. Compared to the way the other characters are so swiftly dispatched, her ordeal seems to last an eternity, and she lets out wild, primal wails with such unceasing, rhythmic regularity that is not only horrible to listen to, but exhausting too. You could argue that these familiar horror tropes of ‘the final girl’ and ‘scream queens’ are exploitatively misogynistic, or that they are liberatingly feminist, but either way there is no denying the power of Burns’ scream to elicit feelings of primitive dread.

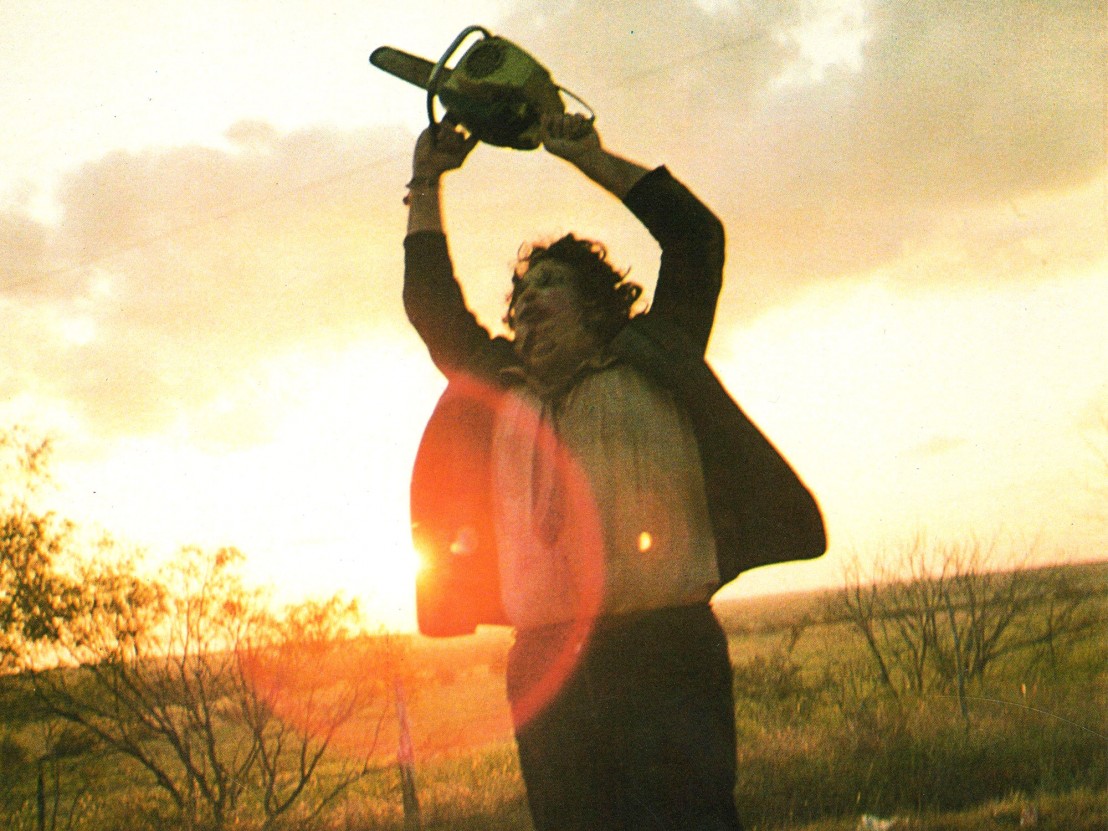

When relief finally comes and the film cuts to black after Leatherface manically whirls his chainsaw around having seen Sally escape, it’s startling just how overwhelming the silence that follows is. So sudden is the change that the extreme silence only serves to emphasise just how loud the relentless cacophony of chainsaw and screaming was, and the sonic void as you watch the end credits and contemplate what you’ve just seen is filled by those horrible sounds ringing in your ears. Other horror movie scores might be skilfully composed to provoke feelings of unease and fear, but the tuneless, horrible, real-world noises that make up the soundtrack of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre are a vital component of this classic, uniquely uncomfortable viewing experience.

Published 29 Jun 2016

By Lara C Cory

The cult director has recorded new versions of Halloween, Escape from New York, Assault on Precinct 13 and The Fog.

Steven Spielberg’s beloved 1993 movie is about so much more than dinosaurs.

By Katy Vans

Karyn Kusama and St Vincent’s Annie Clark are among those contributing to an all-female anthology film.