Guillermo del Toro choreographs a ballet with giants and offers one of cinema’s most beautiful definitions of love.

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Individually, they are an exciting, lugubriously charismatic prospect. Together, however, they are a dream team. They embody the idea that two people can, for a brief moment, come together as one. Not as a single entity per se, but as a man-machine whose parts reverberate in strict tandem. And cinema is a medium which can enable that. The camera observes as people come together. It goads them. It magnetises them.

In the 1935 film Top Hat, Fred and Ginger casually slow dance at a party. He segues into the opening refrains of ‘Cheek to Cheek’: “Heaven / I’m in Heaven / And my heart beats so that I can hardly speak.” The pair drift towards an opulent balcony and their dance takes a turn for the intricate. The instrumental bridge kicks in, fortuitously, and they begin to mimic one another. They move in perfect unison. A mirror couldn’t do a finer job. It’s too perfect. We unconsciously chalk it up to skill and years of hard toil, but the reality is, it’s magic.

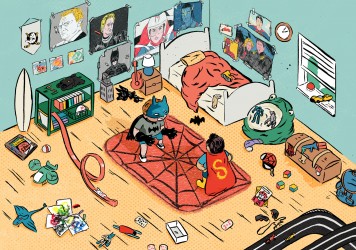

I’ve seen Guillermo del Toro’s 2013 film Pacific Rim four times since its release, and every time it has made me think of Top Hat. I like to think that when del Toro was making Pacific Rim, Top Hat was on his mind too. Or if not Top Hat, then some other classic era Hollywood musical. Maybe one by Busby Berkeley. It’s a film which places the weight of the world’s continued existence on the small matter of human synchronicity. To save the day, it’s not about handing an olive branch to some smashy-smashy overlord, it’s about finding common ground and connectivity within your own camp. Ultimate victory is predicated on overlooking physical obstacles, and for two people to move their bodies and minds as one. As such, Pacific Rim contains all the hallmarks of a musical.

Heading right back to the beginning, del Toro has always been an artist who uses film as a means to project and collect his influences. Sometimes it’s namechecking visual artists or literary figures, occasionally it’s symbolic recreations of his eventful youth in Mexico, and there are probably references embedded deep within the frame that are so obscure, only he knows about them. He has dedicated this film to the late stop-motion wizard Ray Harryhausen, and the original godfather of beast-driven anti-nuclear parables, Ishiro Honda (director of the original Godzilla from 1954). With every film del Toro makes, there’s little doubt that he’s done his homework when it comes to historical connections and landing on a reason to birth it into the world. And yet, if you knew nothing of all this high art under-padding, it wouldn’t make a jot of difference. These touchstones fuel his imagination, so then the films can fuel ours.

One obvious motif that has made an appearance – fleeting or otherwise – in his cinema is that of clockwork parts and analogue machinery. He is an artist who worries about interior workings as much as exterior appearances. It’s a hand-held trinket which grows spidery claws and sets off a trail of bloodsucking carnage in his 1993 debut feature, Chronos, a vampire movie which combines horror genre trappings with a melancholic discussion on ageing, mortality and the ideological disparities between the young and the old. His 2008 comic book sequel, Hellboy II: The Golden Army, comes across as an enjoyably indulgent insider dare to get as many OTT mechanised creatures on to the screen as the budget will allow.

Pacific Rim marks a convergence point in del Toro’s career. It’s where the humans and the machines finally combine as one. To operate the monolithic robot Jaegers which have been constructed to defend the planet against an under-floor infestation of Kaiju (giant reptilian wreckin’ balls with an ingrained mandate to destroy), two people must enter into its skull plate and work the controls manually. But there’s a catch, because it’s not the usual case of just sitting in front of a console, mashing a keypad and hoping the little red warning lights don’t start flashing. To make these machines work, the pilots have to commune with one another on a psychological level. They have to dance together. The process is called “drifting”.

When Raleigh Beckett (Charlie Hunnam) and Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi) are finally able to deal with the emotional baggage accrued from years of living in a world in which a Kaiju attack is a case of when rather than if, they become compatible Jaeger pilots. They are cogs within del Toro’s fanciful contraption, the vital components in making this hulking monolith come to life. Yet the spark of romance is inferred at the moment they meet. In the past, it’s been siblings or family bonds which have resulted in the most robust drift compatibility. But love is a special lubricant which transforms kings into gods. It’s comfortable to move together with kin, but the connection is wilder, stronger, more perilously potent between strangers in love. There’s no question as to whether Raleigh and Mako will eventually get together, but they have to make sure their romance has a context in which to exist. They must, then, save the planet.

Okay, so this argument as to the balletic eminence of Pacific Rim might read as a little obscure, or maybe a mite personal up to this point. But this simple notion of bodies in harmony feeds into broader, more finite reasons for the film’s subtle grandeur. Let’s first acknowledge one convention of 21st century blockbuster filmmaking that was arguably ushered in by Michael Bay in 2007 with his film Transformers: and that is, incoherence. Commentators were lukewarm to that film’s sense-assaulting charms, while audiences flocked in their droves. On a superficial level, Transformers and Pacific Rim have certain overlaps in that they both contain extended sequences of oversized robots laying waste to an urban metropolis. The differences, though, are what make the former a quasi-unwatchable strobing jack-hammer to the solar plexus, and the latter a model of patient visual storytelling, keen spacial awareness and metronomic timing. Pacific Rim is a graceful tango, Transformers is drunken bedroom head-banging.

Bay’s cinematic mandate is that more is always more: more robots; more sounds; more edits; more explosions; more sub-plots; more, more, more. As a filmmaker, he bombards us into submission rather than guides us to safety. He gorges on the image. With Transformers he set a terrible precedent which he then expanded upon with each subsequent sequel. So pointedly incoherent are these films that some critics have even made work of comparing them to the structuralist, non-narrative experiments of Stan Brakhage. But del Toro is clearly someone who values the lost art of using film to supply a basic geographic awareness. Where Bay has no concept of perspective and considering where the viewer is in relation to the action, del Toro appears to use this perspective as the anchor point for each new set piece. Del Toro treats the camera as an eye; Bay treats it as an asshole.

Again, this may seem like a minor aspect of a major enterprise, but it’s the difference between poetry and white noise. One other notable blockbuster of the 21st century, Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla from 2014, also embraces clear-sighted storytelling over a random assault of images, and is all the better for it. Both films use editing as a route to clarity and the escalating of drama rather than garish obfuscation. They want the viewer to see and understand what’s happening. Bay’s gluttonous excesses can be seen more frequently, perhaps reaching their squalid apotheosis in Joss Whedon’s incomprehensible flick-painting, Avengers Assemble, from 2012.

Bay-bashing aside, Pacific Rim must be admired for the wondrous musicality of its central action sequence, in which two Kaiju wreak havoc in Hong Kong. There is little more to say on a narrative level than the fact that we become spectator to a big robot fist-fighting with two big monsters in order to save a city. Their battleground is strewn with tall buildings, which allow for tactical advantages as well as the usual pleasurable carnage. The sequence is captured in long, fluid takes. There is suspense and figures tangled in lustful violence.

Del Toro is almost fussily adamant that we know the distance between things and the shape of the landscape. But this is not a fight sequence, it’s a dance sequence. This is Fred and Ginger, clasped breast-to-breast, swirling in concert as structures topple and plumes of neon liquid cascade into the night air. These are of course CG entities that have been animated rather than traditionally directed, but del Toro doesn’t use this as an excuse to embrace confusion. He impresses with restraint and cogency rather than excess and disorientation. In Pacific Rim, everything is in its right place. The film is about the joy of shared of experience, the dance of death and, eventually, the explosive bliss of rebirth. In a moment of repose, the music stops and the lovers are left with only one thing to do: embrace, cheek to cheek.

What do you think is the greatest blockbuster of the 21st century? Have your say @LWLies

Published 13 Jul 2016

The great Guillermo del Toro talks about his magnificent Gothic ghost story.

Twelve writers pin their colours to the tentpole in our survey of the best summer movies of the modern era.