On July 21st 2023, cinema will see its most unlikely box office battle yet: Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer versus Greta Gerwig’s Barbie. The idea of walking out of the brightly coloured world of Mattel’s iconic doll and straight into the monochrome study of the atomic bomb’s father is a strong contrast, but there’s a case to be made that Nolan and Gerwig’s latest projects could fit right alongside one another.

On a broader level, Nolan and Gerwig occupy a rare level of critical acclaim and commercial popularity for filmmakers in our current IP driven movie hellscape. They both began their directorial careers with an original, personal work from a self-penned screenplay, before moving onto adapting classic works of fiction (Little Women and Batman obviously).

When both filmmakers received their first nomination for the Best Director Oscar in 2018 – Nolan for Dunkirk and Gerwig for Lady Bird – a panel at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival featured all the nominees, and they were asked to name an aspect of each other’s films that impressed them.

When complimenting Dunkirk, Gerwig highlighted the emotional heft of Mark Rylance and Tom Glyn-Carney sparing Cillian Murphy’s soldier from realising he accidentally killed a civilian in his shell-shocked state of panic, and the way it evokes the confusion of war from its opening seconds. Meanwhile, Nolan praised the immersive familiarity of Lady Bird, the precision and completeness of its storytelling, and its portrayal of a kind of mother-daughter relationship you rarely see on screen, perhaps one that reminded him of the father-daughter dynamic in Interstellar.

However, the biggest link between the two came when Paul Thomas Anderson shared his admiration for both movies. He described the unique pleasure of watching the scale of Dunkirk and wondering “how the f*ck did he do that?”. But then Anderson turned to Lady Bird, describing the experience of watching Gerwig turn Saoirse Ronan into a teenage girl from Sacramento and wondering “well how did she do that?”.

Anderson said: “That’s the best feeling, when you feel a magic trick in front of you because all the things you know about being a director sort of go away.” For all the analysis you can bring to Gerwig and Nolan’s oeuvres, their aesthetics work to create these fully immersive, accessible movies that function as stellar entertainment as well as uniquely personal visions.

But the connections go beyond simply saying “Gerwig and Nolan met once”. In complementing each other’s work, they highlighted their talents for evoking a specific time and place with their filmmaking. In Lady Bird, Gerwig acutely renders the environment around its titular character and how it affects her development. A version of Lady Bird that does not familiarise you with Sacramento is a version where the ending of the film isn’t as powerful. Both Lady Bird’s departure and her small reconnection with her home are rooted in an assured familiarity we’ve built up over the last 90 minutes.

The beaches of Dunkirk are quite a long way away from Sacramento, but Nolan’s evocation of environment is equally essential to his 2017 film. Image after image of those confused soldiers lost within the vast vacuum of a seemingly never ending beach, trapped against an ocean that stretches on forever, is a powerful source of tension. The claustrophobia Nolan conjures from such a wide expanse is what makes the rescue of those soldiers seem more miraculous. Two very different stories, but each of them ultimately works because they are deftly aware of the space those stories take place within.

After her debut Gerwig wasted no time in upping her storytelling ambition, using a non-linear structure to adapt Louisa May Alcott’s seminal literary work. Nolan is also fond of playing with the structure of his stories, and no, the connection here isn’t simply to say they both tell things out of order. Gerwig and Nolan both employ non-linear narratives to comment on the broader messaging of their work. Gerwig uses the contrasting structure to tell a faithful adaptation of Alcott’s novel while also commenting on the publishing system that forced the author to marry off her lead character. It’s the story of Alcott’s novel that transcends the boundaries of that narrative to become the story of Alcott.

Meanwhile in Memento, Nolan’s screenplay is structurally complex not just for the sake of fooling the audience, but for critiquing the very nature of unreliable narrators. Leonard’s fatal flaw is that he is too trusting of the person supplying him with information on his own fractured memory and distorted narrative, and the order in which Nolan provides that revelation makes that flaw more tragically obvious.

Little Women also deploys its non-linear narrative as an exploration of memory. The film’s structure suggests all the early chapters of the book are Jo’s stream of consciousness nostalgia evoked by her journey back home. Nolan’s films have no shortage of men trapped in the vestiges of their own haunted past as a refuge from their horrible present, from Inception’s Cobb to Interstellar’s Cooper.

Parenthood has played a part in both filmmakers careers as well, such as the parent-daughter dynamic that drives Lady Bird and Interstellar. For Nolan there is also the motif of Cobb’s children and his desire to be reunited with them in Inception, and while the four March sisters are the focus of Little Women, Gerwig never loses sight of Laura Dern’s Marmee. So many important parts of the March sisters story are filtered through their relation to their mother, whether it’s her attempts to heal the rift between Jo and Amy after the book burning or revealing Beth’s death in the form of reading the expression on Laura Dern’s face.

Nolan frames his themes of parenthood from the eyes of fathers forced to leave their children behind, using Cobb and Cooper’s desire to see their children again as a driving force for both protagonists. Gerwig’s musings on parenthood are framed through stories of daughters seeing their parents as people for the first time. You see this in Lady Bird gaining a new perspective on her fathers battles with mental health, or the March sisters gradually leaving their own childhoods behind.

Looking ahead, Oppenheimer and Barbie both see their filmmakers tackling complex figures, albeit very different ones. Since her creation in 1959, Barbie has proven empowering to young girls but also restrictive in Mattel’s application of specific body types and beauty standards. Robert Oppenheimer’s work was a scientific breakthrough that also unleashed unforeseen destruction upon humanity. Despite being radically different, they offer each filmmaker a rich framework to develop their existing patterns of telling stories of multifaceted characters, from Lady Bird to Bruce Wayne.

As dramatic as this contrast seems, what we have here are two accomplished filmmakers releasing their new projects. They’ve both explored the personal and the universal sides of storytelling, playing with structure and narrative while demonstrating a distinct directorial vision. Barbie and Oppenheimer may appear to target different demographics, but I’ll be in line for both come July 21st.

Published 7 Feb 2023

Saoirse Ronan experiences growing pains in Sacramento in Greta Gerwig’s delightful indie comedy.

Christopher Nolan’s breathtaking historical opus attempts to give the viewer a taste of what war actually feels like.

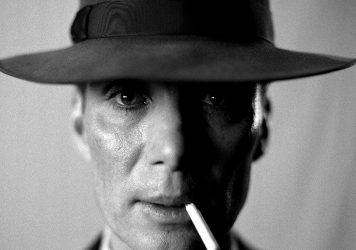

The British writer/director has lined up an all-star cast for his forthcoming biopic of the father of the atom bomb.