When we sit down to watch a film, we do so with a degree of trust that what we’re about to see will be true within the world of the film. So when a filmmaker decides to tell their story from the perspective of an unreliable narrator, as Christopher Nolan does in 2000’s Memento, we are forced to reassess and search for new meaning.

The search for truth and meaning is at the very heart of Memento. Leonard’s (Guy Pearce) search comes in the form of avenging his wife, and while the murder-mystery storyline – along with the femme fatale figure, narrative voiceover and black-and-white cinematography – are all hallmarks of classic noir, Memento’s structure and the way it depicts the malleable nature of memory makes Leonard’s search for truth and meaning endlessly futile.

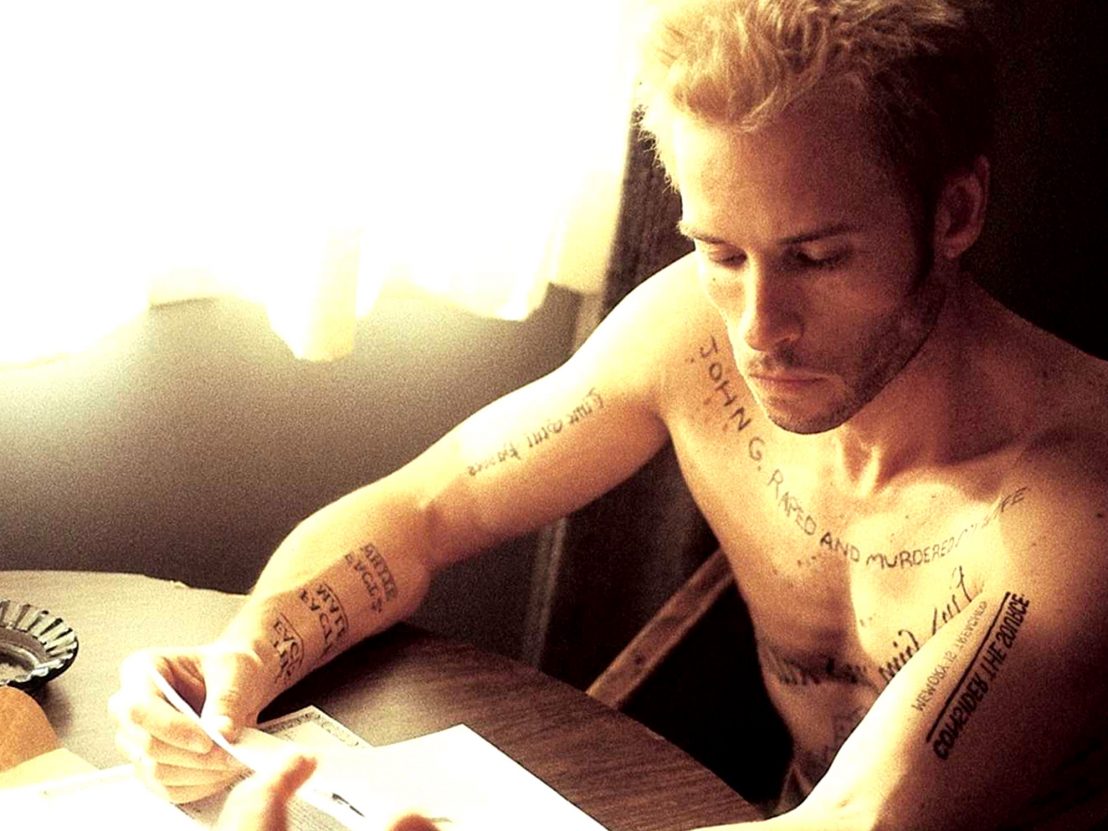

This is best evidenced in Leonard’s tattoos, as well as the Polaroids and notes he keeps. These tools are the means with which he records his short-term memory and manages his day-to-day life. He appears to function well enough at first, but when it becomes apparent that what Leonard believes to be true is objectively false, we realise that these tools are merely validating his distorted reality. Or, what philosopher and cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard might call his ‘hyperreality’: a simulation which has become more real to Leonard than reality itself.

According to Baudrillard, a total understanding of human existence is impossible and beyond our comprehension because we have become overly reliant on signs and symbols. Excessive efforts to gain a complete understanding of our reality results in us being enticed by a state of hyperreality. This is ultimately what happens to Leonard: he depends entirely on his tattoos, Polaroids and notes, and the more he tries to create a coherent picture and edge closer to the truth, the more he is seduced by his hyperreality.

For instance, Leonard even goes so far as to hire a prostitute to play his dead wife. In the moment where she wakes him up by slamming the door, he is able to suspend himself in the belief that his wife is still alive. Additionally, each time Leonard is challenged he falls back on his notes and Polaroids and further into his hyperreality, such as when he chooses to ignore Teddy’s (Joe Pantoliano) warning against the manipulative Natalie (Carrie-Anne Moss). Tip-toeing around the truth, Leonard reacts like a stubborn child, reciting his backstory like a script: “I don’t have amnesia. I remember everything right up until the incident. My name is Leonard Shelby. I am from San Francisco.”

At the film’s climax, where the backwards-flowing coloured scenes and chronological black-and-white scenes meet, Teddy reveals to Leonard (or rather, reminds him of) the actual truth. That he is responsible for his wife’s death and that he invented the story of Sammy Jankis to cope with his guilt. “So you lie to yourself to be happy,” he tells him. “We all do it.” Through this, Teddy exposes the meaninglessness of Leonard’s endless, cyclical search for the truth. He is, in Teddy’s words, “playing detective.” Teddy pays the ultimate price for this, but because Leonard will soon forget, he is able to set himself off on another aimless path of redemption.

Leonard’s experience within Memento reflects our experience of watching it. We try to make sense of what is in front of us and put the pieces together, but because we are totally subjected to Leonard’s view of the world, we experience the non-linear story as Leonard does. Nolan has even said that he’s seen the film hundreds of times, but can walk into a screening and not know which scene comes next, and that people who worked on the film with him still argue about the various interpretations of it today.

“I have to believe in a world outside my own mind. I have to believe that my actions still have meaning, even if I can’t remember them.” Leonard’s ultimate goal is for his life, even if he cannot remember most of it, to have meaning. Deep down, he knows that it can’t, but by constructing his own fake puzzles to solve and hyperreality to live in, Leonard never needs to face the truth. He has the luxury of forgetting, after all. But he cannot go on like this forever. Reality will, one day, catch up with him.

Published 5 Sep 2020

The director’s atmospheric 2002 film makes the most of its remote setting.

This new video essay by Luís Azevedo explores one of the director’s major obsessions.

Never has on-screen magic been so compelling as in the director’s now 10-year-old passion project.