Winter in Alaska can be desperately bleak, and that’s not simply because of the sub-zero temperatures. If you follow the narrow road to the deep north, beyond the boundary of the Arctic Circle, you’ll eventually come to a place where the days seem to last forever. At the height of summer, the sun doesn’t dip below the horizon for 60 days straight. Sleep is elusive, the world takes on a strange new presence, and evil things are no longer reserved for the night only. As such, it’s only natural that in 2002 Christopher Nolan sought this land of always-daylight for his psychological thriller Insomnia.

The first shot of the film’s setting is glimpsed from a seaplane cruising above a glacial wreck of tundra and ice ravines. The rising monoliths of its lumber mills are the only landmarks for hundreds of miles, and it sits in the shadow of a towering, pine-clad mountain range. “There’s just nothing down there. I haven’t seen a building in, like, 20 minutes,” uttered by LAPD detective Hap Eckhard (Martin Donovan), is the film’s short and simple introduction to Nightmute, a town on the edge of the world. Eckhard and his partner Will Dormer (Al Pacino) are flying in to assist with the homicide investigation of local teenager Kay Connell (Crystal Lowe), and their jet lag is only the tip of the sleep-deprived, hallucinatory iceberg awaiting them.

Insomnia marks the moment where Nolan’s signature themes – disconnection, isolation, the fragility of the human mind – come together to intoxicating effect. Throughout the film, Dormer struggles to adapt to the constant daylight and drifts in and out of his detective work, hearing noises and seeing apparitions where none exist. One particular episode of his dreaming-wide-awake fugue, captured by Wally Pfister’s icy cinematography, sees Dormer stranded in a fog bank in pursuit of Kay Connell’s ostensive killer. In one quick instinctive motion, Dormer fires at a figure in the mist only to discover that he has in fact shot his partner.

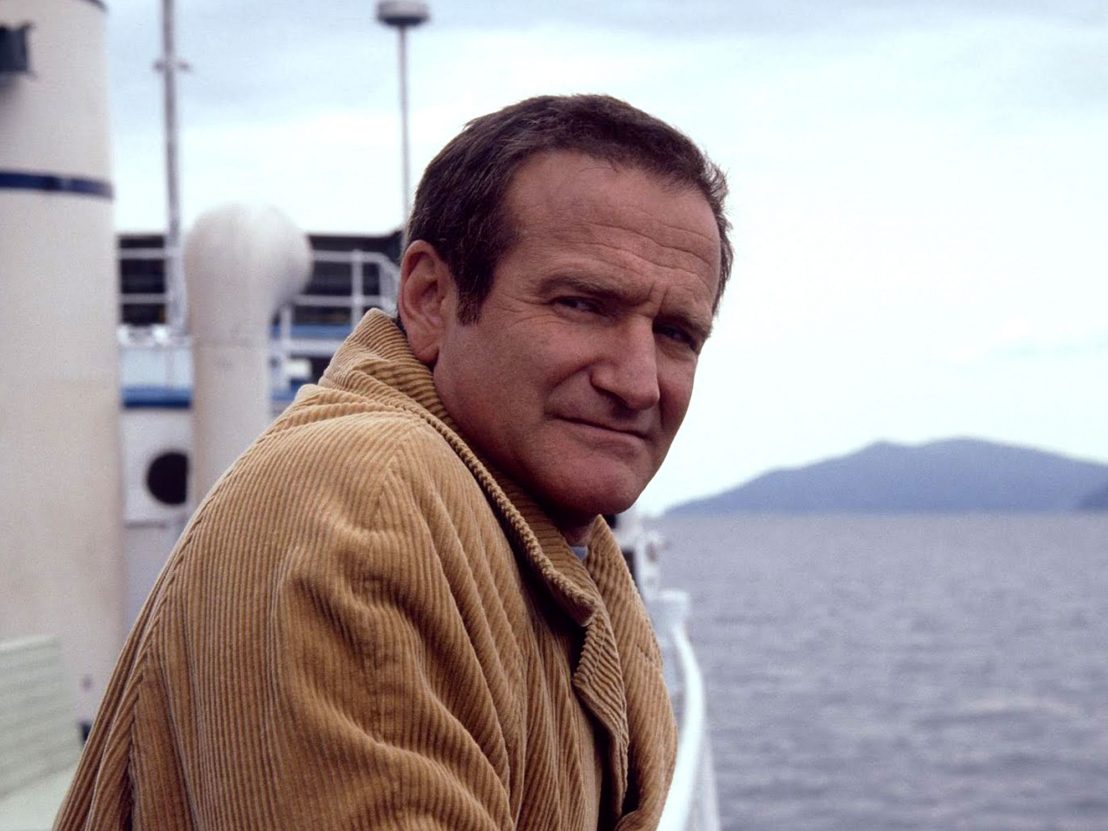

The landscape that hosts Nolan’s moody crime thriller seems to claw at the ankles of the newcomer detectives, luring them into the woods, into the fog, and always into danger. Pacino, in one of his finest late-career performances, brings an astonishing level of grief and despair to Dormer, a man who is far from the sunshine and warmth of the Golden State.

The same oneiric qualities present in two of Nolan’s other films, Memento and Inception, are at their most raw in Insomnia, as Nolan eschews a simple narrative for one filled with ambiguity, mistrust and unease in an apparently typical American logging town. Close-knit communities have long provided compelling backdrops for slow-burn mysteries, with Twin Peaks among the most notable examples of what happens when a director looks behind the curtain of small-town America.

Near the end of Insomnia, there are several tracking shots of Hilary Swank’s bright, fearless detective Ellie Burr as she drives through the mountain heartland towards her husband’s lakeside cabin. Robin Williams’ Walter Finch is the film’s most troubled and lonely character, and he awaits her arrival like they are the last two people on earth. The journey to his cabin is dwarfed by the verdant hills rolling on forever, and the impossibly large expanses of wilderness with no houses in sight.

The film’s climactic finale owes much of its tension to these gradual establishing shots, which paint the vastness of Alaska in all its cold and desolate menace. For all of Insomnia’s familiar plot details, there is only an unfamiliar hostility to be found in its setting. A testament to the power of location and use of space, Insomnia reveals a filmmaker as attuned to this natural landscape as they are to the characters inhabiting it. They, like the audience, can’t help but become lost in it.

Published 15 Jul 2017

Life’s a beach as we take a deep dive into Christopher Nolan’s wartime suspense saga.

Never has on-screen magic been so compelling as in the director’s now 10-year-old passion project.

By Anton Bitel

In Christopher Nolan’s urban epic, Batman takes on The Joker… or should that be, George W Bush takes on Osama Bin Laden?