From The Favourite to Dickinson, anachronism has become a popular trope of the post-millennium period piece, where 18th-century Queen’s parties are soundtracked by New Order and wigged Whigs breakdance. Few films have had as profound an influence on this trend as Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman’s Contract, bringing an abundance of absurdity into this once prim and stuffy genre.

Mr Neville (Anthony Higgins), a conceited, darkly handsome artist, is hired to produce 12 landscape drawings for Mrs Herbert’s (Janet Suzman) distant husband – an offer the opportunistic Mr Neville only accepts in return for sex. He produces a different pencil sketch of the exterior each day, demanding an unimpaired view of the house. But Mr Neville’s lack of cathedral thinking ultimately leads to his downfall.

The idea for The Draughtsman’s Contract was born out of a holiday to Hay-on-Wye in which the director spent his time drawing the local architecture. Mr Neville is a man with clear but outlandish demands, and it is not hard to see him as a surrogate for Greenaway. Throughout his filmmaking career, Greenaway has always questioned the role of the artist, and the hands in Mr Neville’s drawing are in fact the director’s own.

Twenty-four years before Sofia Coppola brought Converse into the 18th century, Greenaway envisioned a film engorged with anachronisms. An initial three-hour cut featured a cordless telephone and the director’s own approximations of Roy Liechtenstein paintings on the walls. Unlike the drawings in the film, Greenway interpolates, and never imitates. He presents history through a distorted circus mirror, Mannerism warped with a 20th-century attitude. A history where draughtsmen throw apples at statues and everyone speaks in a surreal panto-timbre.

In recent years, Greenaway has been vocal about the need for an ‘image-based cinema’. Yet in this cutting comedy of manners he allows his grasp of the English language to shine, with deliciously acerbic lines such as “Carp live too long, they remind him of Catholics” and “Why is this Dutchman wagging his arms about, is he homesick for windmills?” It might be a stretch to suggest that the film acts as a kind of proto-Twitter, where funny quips and one-upmanship are used in lieu of level-headed discussion, but a barb aimed at Mr Neville, “I will cancel your eyes,” has an unintended pertinence today. Had it been released today, one can easily imagine the film being endlessly quoted and memed online.

Greenaway adopts a less-is-more visual approach, the elongated, wide-angle shots spotlighting the military-grade quips and palatial setting. The once aspiring painter made the switch to film after stumbling across Last Year at Marienbad and Breathless. Here he has his cake and eats it, referencing 17th-century painting and ’60s Euro cinema. The operatic tableaus on display here could have been pulled straight out of the Renaissance era. The long tracking shots over dinner feel like the French New Wave estimation of a Rembrandt, a subject Greenaway would return to 26 years later.

The Draughtsman’s Contract is a film of old clothes and new attitudes. Of verbose language and Barry Lyndon-esque visual symmetry. Black-and-white sketches backdropped by painterly cinematography. And then there’s the score by Micheal Nyman, a composer who found his voice playing Mozart like Jerry Lee Lewis, which recalls dance music with its subtly varied repetition (although the harpsichord transports you straight to 17th century England). Nyman’s work reflects the bravado and routined excesses of the characters, employing a range of historically inaccurate instruments. It’s no surprise that the piece ‘Chasing Sheep is Best Left to Shepherds’ was sampled by the Pet Shop Boys on 2013’s ‘Electric’.

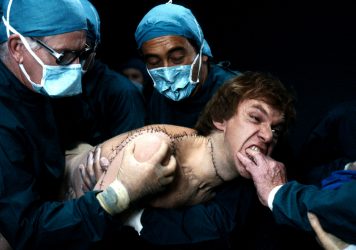

In many ways, The Draughtsman’s Contract feels like an hors-d’œuvre for Greenaway’s 1989 Thatcher-satire The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, which dials up the grotesqueness of his characters to 11 and features an even louder, longer Nyman score. “I do not disguise or disassemble” says Mr Neville at one point in the film, but Greenaway dismantles the past and disguises it with his own image. However, the impending (and historically accurate) Married Women’s Property Act hangs over the male characters.

This is where the influence of Greenaway’s film can be felt most keenly today. Just as Mr Neville is finally outmanoeuvred by Mrs Herbert and Mrs Talmann – his lifeless body discarded in the moat – so the women of modern period pieces like Hulu’s The Great take control from their foolish and impotent male counterparts.

Published 12 Nov 2022

Sofia Coppola’s opulent period drama explores female self-empowerment in a man’s world.

Olivia Colman is sublime as Queen Anne in Yorgos Lanthimos’ absurdist period tragicomedy.

Lindsay Anderson’s spiky Thatcher-era comedy is the perfect sign off to his Mick Travis trilogy.