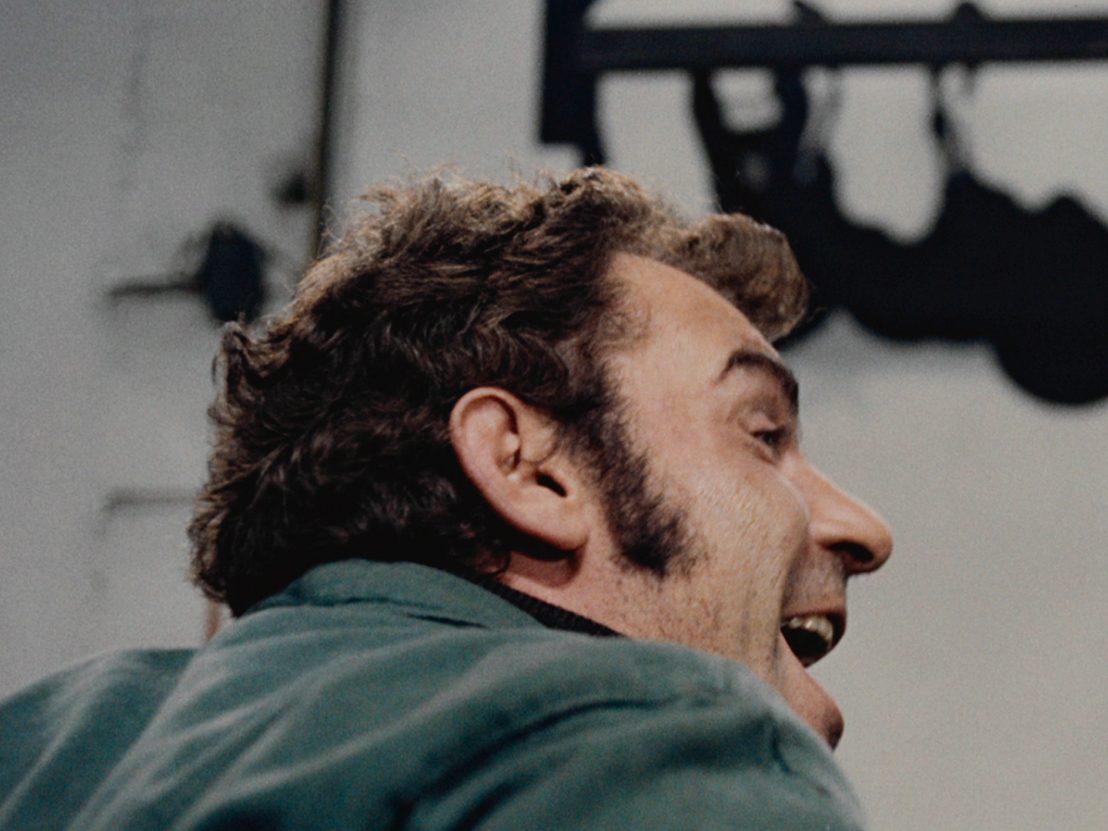

Ludovico Massa (Gian Maria Volonté) – known to everyone as Lulù – wakes in a nightmarish sweat at the beginning of Elio Petri’s The Working Class Goes To Heaven (La classe operaia va in paradiso, aka Lulu the Tool). It is 4.40am, and he is surrounded by the sound of a clock’s ticking and the rhythmic snoring of his partner Lidia (Mariangela Melato). Lulù’s diurnal hours too – much like Ennio Morricone’s pulsing ‘industrial’ score for the film – are filled with the metric rhythms of the factory where he labours and marks out his passing life as a production-line piece worker.

By the time, some two hours later, Lulù has been woken again by the morning alarm and brought Lidia her morning coffee in bed, he will regale her and Arturo (Federico Scrobogna) – Lidia’s young son by another man – with his theory that even his own body has a shit-producing ‘machine’ in it, ‘just like a factory’. Much later, when Lulù picks up Arturo from school, he will comment (twice!) that the boy and his fellow pupils, pouring through the gate, “look like little factory workers”.

If Lulù regards both his own body and his adopted son’s school as being like a factory, the actual factory where he toils all day is variously likened to a ‘prison’, a ‘nuthouse’ and ‘hell’, even as Lulù will declare, “I’m a machine!” and, after enumerating all his body parts, will expressly compare himself to an animal. What seems missing from this mechanised view of the world is much room for humanity, no matter how loudly larger-than-life Lulù himself may be. For all his irrepressibility, Lulù’s blue-collar subsistence has ground him down.

This is perhaps best emblematised by Lulù’s impotence. It is not so much that he lacks sexual drive, as that by the time in the wintry evening he has come home to Lidia he is exhausted from his work, and that the work itself, rhythmic and repetitive by nature, consumes all of Lulù’s erotic energy.

This is made explicit: for as the workers enter the factory in the morning, they are greeted by a speaker on the tannoy telling them to “treat your machine with love” and to “respect its needs”; and Lulù informs a new recruit that he keeps the right productive pace for his machinework by picturing it as the butt of female colleague Adalgisa Tati (Mietta Albertini). “And off I go,” he says, pounding the equipment percussively, “One piece, one ass. One piece, one ass. One piece, one ass. One piece, one ass. One piece, one ass.” Here work is a sexual surrogate.

Lulù’s impotence marks a broader powerlessness. Having worked factories since he was 16, and now 31 (though looking a lot older), Lulù is working class but no hero, and has long since resigned himself to the bump and grind of his job, and to the demands of his distant bosses. At the factory’s gates he ignores the calls of the unions to organise for shorter hours and more regulated piece work, or of the communist students for strikes and violent revolution, and instead uses his skills and experience to work ever faster, incurring resentment from fellow workers whom the bosses expect to keep up with his rate of production.

Yet as the opening sequence implied, this is a film preoccupied with Lulù’s awakening – and that will come when he loses a finger in a workplace accident. Disillusioned by the sacrifice that the factory has demanded from him, Lulù is drawn to the extreme left and the activism of the students – until, that is, he loses his job, Lidia and Arturo, becomes disillusioned once more, and is made to realise, perhaps too late, that there is power in a union.

If these attacks on both the exploitativeness of the capitalist system and the disunity of the left sound like agitprop, the earthy messiness of Lulù’s character – a bad father (but good to Lidia’s son), a philanderer, demonstrative, volatile, selfish – confounds the film’s politics. Indeed, as the (similarly messy) leader of the students Marx (Donato Castellaneta) tells Lulù, “Your case is singular. Personal. That’s not what we’re interested in. We look at class dynamics.” Lulù’s raw individuality cannot easily be accommodated by any ideological theory – and while The Working Class Goes To Heaven is full of conflicting ideas shouted through bullhorns, Lulù remains an awkward, time-serving misfit. When Marx says, “Our work is aimed at igniting contradictions”, he might as well be describing Petri’s work too.

“I’d be at the table and dream of still being at the factory,” says Militina (Salvo Randone), Lulù’s former mentor who now resides in an asylum, sent mad by all the dehumanising labour, and by his sudden realisation that, after years of work on the production line, he did not have any notion of what he had been helping to make or what all his effort was for.

Lulù too, summarily fired and left out in the wintry cold with no sense of who he is or what his purpose is anymore, goes off the rails, bitterly muttering some of Militina’s phrases to himself and behaving in an ever more unhinged manner. Petri may deliver him a happy ending, with Lidia and Albert returned, his job reinstated, and the unions victorious, but whether this is real, or just another madman’s deluded dreams of still being at the factory, is left very much open to question.

Perhaps, after all, Lulù is about to wake up once more in a nightmarish sweat from his vision of proletarian utopia to a bleaker, more infernal reality for the working class. As he struggles to sleep, and to dream, alongside a woman who chatters her teeth at night, Lulù is an improbable antecedent for Henry Spencer in David Lynch’s Eraserhead, mixing realism and surrealism into an industrial aesthetic, and wondering whether, for all the insurmountable walls, impenetrable fogs and icy misery of the working world, maybe in heaven everything is fine.

The Working Class Goes To Heaven is released on Blu-ray by Radiance, 2nd January, 2023

Published 4 Jan 2023

The star of the riotous Our Ladies talks classism, taking teens seriously and why Derry Girls comparisons are off base.

The American novelist and former Richmond Fontaine frontman discusses the latest adaptation of his work, Lean on Pete.

Maria Speth’s intimate non-fiction epic profiles a spiky but saintly German schoolteacher and his students.