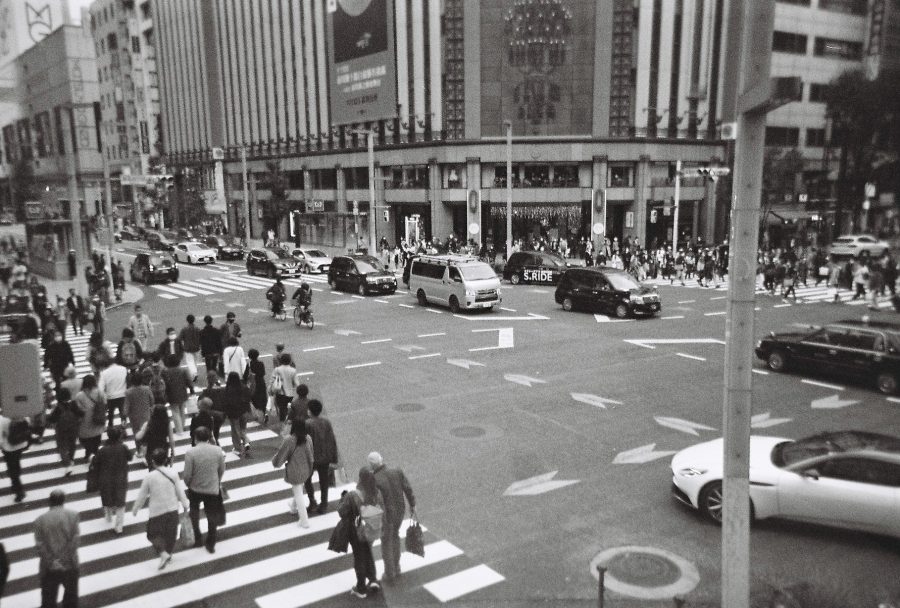

The fast paced world we live in today thrives on the constant movement of people. Our attention is relentlessly being fed into the stream of new information provided by digital and social media. Competitive job markets have transformed us from collective to individual beings, clawing our way through a career in the hopes of achieving a big dream, just to find ourselves clambering to stay alive. The transition between liberating youth and bustling adulthood has not always been kind to me. I find myself under stress and uncertainty of my own future – a moment spent resting or having fun is immediately followed by a feeling of unproductivity.

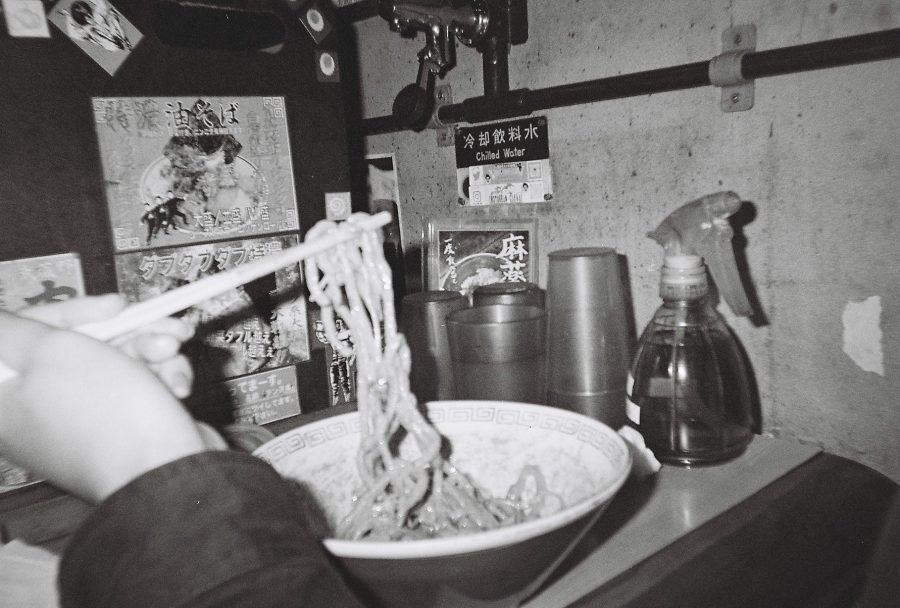

In the context of a world that is rushing you to get ahead in life, films like Hirokazu Koreeda’s After Life and kogonada’s After Yang become a great reminder to find intimacy in the short and fleeting seconds. In an attempt to remember (read: romanticize) the small moments in my life, I purchased a disposable film camera. Being a lover of movies, I thought perhaps freezing a moment in a single frame would remind me that joy, affection, sadness, and all the things that we are alive to feel happens to all of us and not just characters on screen.

Among the many similarities of After Life and After Yang is the languid pacing; a slow exploration of loss and humanity that contrast the rapidly changing world. Aspects of realism engulf the two films despite both stories existing in an alternate, other-worldly universe. Director Hirokazu Koreeda emulates documentary-style filming by introducing interview-formatted monologues and frequent uses of long-take handheld scenes. The audience acts as observers and conversation participants as well. Comparably, kogonada’s sci-fi film retains the familiar aspects of life through visuals and sound. Without overtly fancy set design or CGI, After Yang revels in nature imagery and the ambient sounds of domestic backyards.

The stylistic palette of the two films sets a tender and nostalgic tone for exploring themes of grief – not only for the living, but for moments passed. In After Life, a group of newly deceased are compelled to select a memory to carry with them throughout eternity; a memory that would sum up their time on earth. Meanwhile, the afterlife bureaucrats – who in their own way, are unable to move on from their deaths – are tasked with the duty of guiding the deceased with choosing and manifesting these memories into film.

In After Yang, the sudden passing of the android older brother Yang guides the family to his memories, which comes in the form of short videos taken each day of his life. Through Yang’s recordings, the family gets a glimpse into his past lives and in turn, discovers his inner thoughts and emotions – something they never thought would have been possible for a programmed robot to carry.

After Life and After Yang propose similar ideas about the moving image: a capsule of life. Memories – more specifically the fragmented, intentionally framed, deliberately nitpicked memories – gives the characters’ death sentimentality. Display of vulnerability and remorse comes forward, rendering whatever “purpose” or mark they may leave on earth insignificant.

Among the group of recently deceased in After Life is Mr. Watanabe, a widowed man who spent most of his life working until retirement. Only remembering the tedious corporate routine and a humdrum arranged marriage, the old man felt dissatisfied with his life and refused to choose a memory. In the end, it was a warm autumn afternoon of sharing a park bench with his late wife which Mr. Watanabe decided to bring with him forever. For Koreeda, memories shape identity, so when Mr. Watanabe is granted the opportunity to have his life be defined by a single moment of peace and affection, his soul is no longer bound by the shackles of work and a colorless existence.

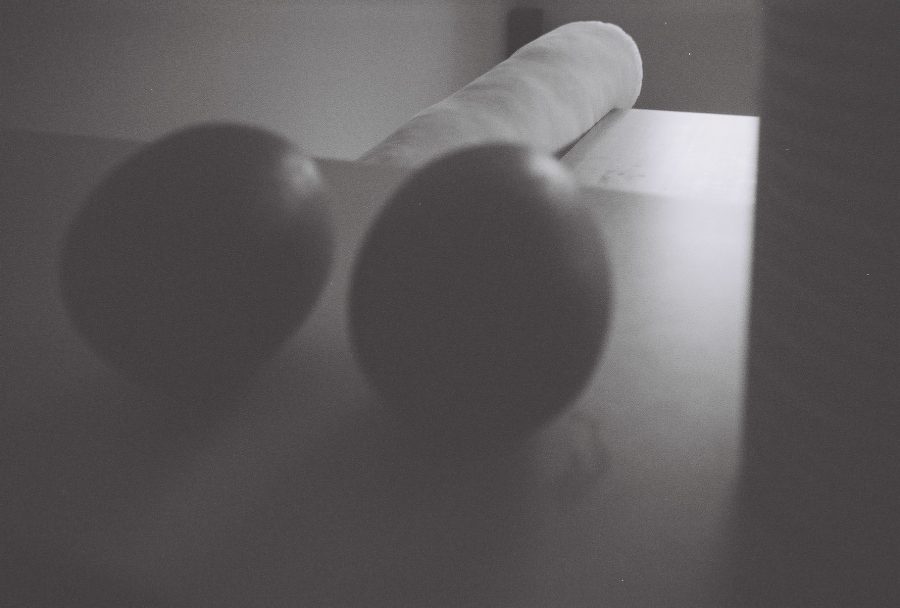

Similarly Yang, whose purpose on earth was to fulfill a functional role, displays a sense of individuality through his recordings. Filling his memory bank are images of trees, a shared embrace between parents, the swirling dry leaves in a warm cup of tea, and other ordinary occurrences. Accompanied by the soft pianos of composer Aska Matsumiya and cinematography that echoes many of Koreeda’s dramas, koganada frames Yang’s individuality in such a humane way that contrasts the sci-fi convention of a rational and soulless robot.

In kogonada’s video essay about Hirokazu Koreeda for Sight & Sound, he mentions the way the Japanese filmmaker captures mundanity. Daily activities and routine are portrayed in a compassionate and romantic way, but in a familiarity that doesn’t stray too far from the everyday. In the grand scheme of things, when we take on a journey towards a big goal, achieve an impressive milestone, or get too caught up in the flurry of career or studies, what may go unnoticed is an appreciation for the uneventful and small moments of intimacy; In sharing meals, train rides, comfortable silences, or in the sunlight that sifts through trees. This value for the seemingly insignificant pauses can be found rooted in After Life and After Yang. It is mundanity that characters chose to return to during death.

Through the passage of time, nothing survives. Revisiting the past (perhaps through the opening of a photo book or a conversation with an old acquaintance) is often nostalgic and painful. What fills us is a yearning to go back in time, or a sense of regret for not cherishing something enough. Before we knew it, time has forced us to move on to other things, other people, and other dreams. But I believe that it is not because time is cruel that we have regrets, it is that we often let these things fleet away before we have the chance to fully embrace them for what they are.

Published 17 Feb 2023

One of Japan’s best living directors tells us about adapting manga and mimicking Ozu.

Kogonada’s sci-fi-tinged family drama confirms its writer/director as one of cinema’s most vital new voices.

Hirokazu Koreeda's latest tale of found families focuses on an illegal South Korean adoption scheme, run by two grifters with hearts of gold.