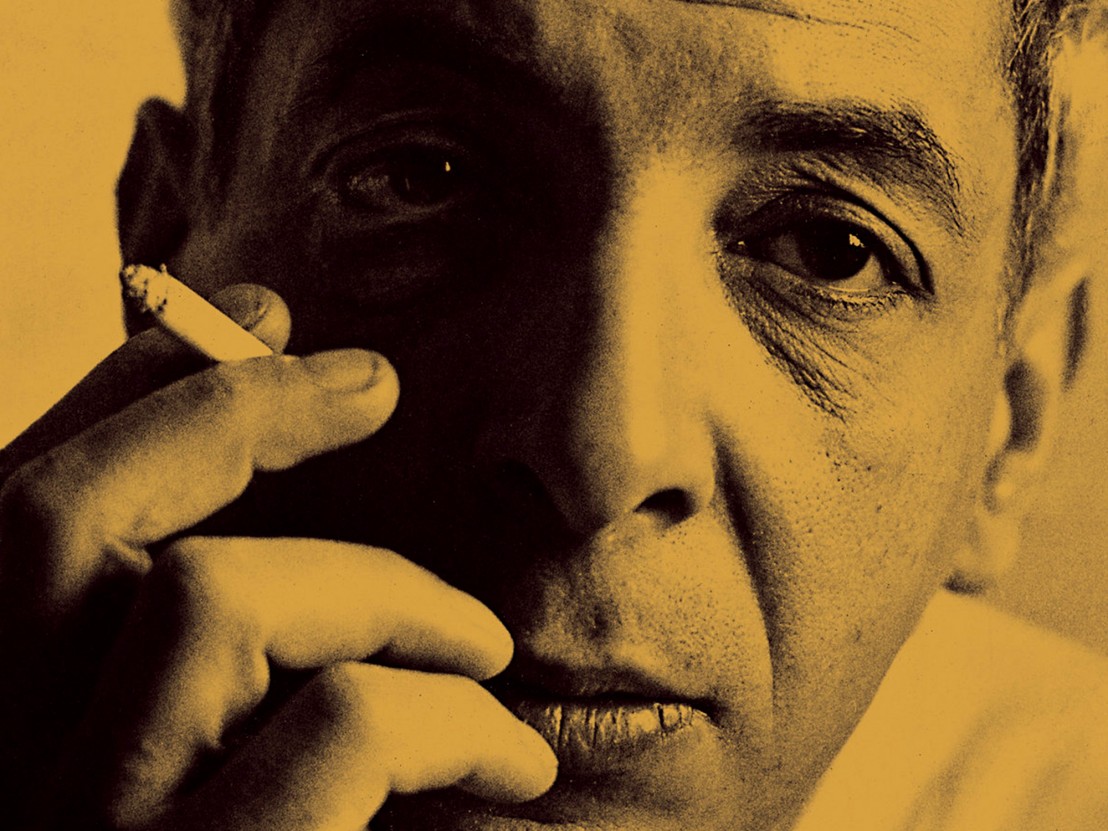

Having scored over 130 films during his lifetime, as well as classical music for more than a hundred ballets and operas, Mikael Tariverdiev’s place in the pantheon of great composers should be all but assured. As is so often the case, however, fate had other plans and his work has remained almost completely unknown outside his homeland for decades.

With a unique mix of deceptively simple piano melodies, lush brass sections and contemplative romances that conjure images of evocative smoke-filled scenes, the timeless quality of Tariverdiev’s work eschews any easy comparison, even today. At a time when vinyl reissues are increasingly helping to raise the profile of iconic and lesser known composers, now is as good a time as ever for audiences to discover his legacy courtesy of a new three-disc compilation.

Born in Georgia in 1931 to Armenian parents, Tariverdiev rose to prominence in Russia in 1964 alongside his friend, director Mikhail Khalik, on the coming-of-age film Goodbye, Boys! Little seen outside of Russia, where it has attained cult status, the film follows the story of three teenagers graduating from school during World War Two, whose plans for a carefree summer are scuppered when they are instructed to enrol in military service.

Having first met as students in 1956, Khalik and Tariverdiev went on to develop a friendship that would see the duo producing several films together until the early 1970s when Khalik’s refusal to cooperate with state censors led to his defection to Israel. “Our work developed in tandem quite naturally of its own accord,” Khalik recalls. “At first it was because we were both young and shared the same notions of beauty, and after that first collaboration, I did not want to work with anyone else. I saw and heard in Mikael’s music, in his style, a sense of harmony that was close to my own.”

They had much in common, particularly a disregard for authority. “The most important thing was our sense of freedom. Of course we understood what kind of place we lived in; one had to deceive the authorities to get anything done. Nevertheless, we were free on the inside and never gave that much thought, or we did so only after we had finished something. Then we would sit there thinking if it would get passed by the censor or not, and what we had to do and what kind of lies to tell for that to happen. But in the middle of working on something, I remember very well that we felt completely free.”

While the collision between music and cinema served as the root of his passions, Tariverdiev also sought to explore alternative musical outlets. Working with Khalik again on Sandu Follows the Sun, he opted to experiment with vocal cycles, overlaying poetry with music. Combining Russian prose against impressionistic scenes, it was an approach that marked the beginning of an aesthetic he would seek to develop further throughout the 1960s, which he later dubbed ‘The Third Trend’.

Tariverdiev’s style went against Soviet musical academic traditions, with vocal cycles often sung by the composer himself with an emotional delivery not dissimilar to the French Chanson style common to the Nouvelle Vague. The result is a diverse selection of material, much of which wouldn’t seem out of place alongside the early works of Godard or Truffaut.

Ever the pioneer, Tariverdiev would later divide his time between film and television projects. His small screen credits include the 12-part series Seventeen Moments of Spring and the romantic comedy The Irony of Fate, the latter of which remains one of Soviet television’s most popular productions enjoying regular re-runs on national television during the festive season.

In spite of his relative obscurity outside of Russia, Tariverdiev’s work resulted in many Soviet and international awards, among them an American Music Academy’s award in 1975 and three Nika awards (Russia’s equivalent to the Oscars) for the Best Film Score in 1991, 1994 and posthumously in 1997. He also went on to become Head of the Composers’ Guild Of Soviet Cinematographer’s Union and, following his death in 1996, the Mikael Tariverdiev Charity Fund and Tariverdiev International Organ Competition were set up in his honour, both of which continue to help nurture young musical talent to this day.

‘Film Music’, the first compilation of Tariverdiev’s material to be made widely available, has been made possible largely thanks to the support of his widow, Vera Tariverdieva, who supervised new transfers of Tariverdiev’s original tapes and reel-to-reel machine. This long overdue release provides a rare opportunity to discover a prolific musical visionary whose output has lost none of its potency.

Mikael Tariverdiev’s ‘Film Music’ is now available to buy on three-disc vinyl, CD and digital download from Earth Records. An Evening of Tariverdiev takes place at Pushkin House on Friday 4 December. Tickets are available at pushkinhouse.org

Published 4 Dec 2015

The composer on what audiences can expect from the director’s forthcoming crime thriller.

The Buenos Aires-born, Paris-based provocateur sounds off on all things Love.

By Jordan Cronk

Pedro Costa returns with his first feature since 2006. The result is nothing short of spectacular.