With a solid filmography built on personal tragedy and existential crises, it’s fair to say that Denis Villeneuve’s films don’t hold your hand. In fact, any hand offered is likely that of a doppelgänger, a mirage, or simply a figment of your own unquiet mind. In anticipation of his upcoming sci-fi drama Arrival, we’ve compiled a list of five key moments in Villeneuve’s previous films where human trauma is at its most vulnerable, stark and disturbing.

Of all the bloodshed and death in Villeneuve’s third feature, a retelling of the ‘Montreal Massacre’ shooting at L’Ecole Polytechnique in 1989, it is the suicide of heroic Jean-Francois that speaks the loudest about the fragility of the human mind. The tragic murder of 14 women at the hands of ‘The Killer’ (unnamed in the film, though the character is based on real-life killer Marc Lepine) render Jean’s life void of any light. His failed attempts to save the lives of some of the victims, and his regret at abandoning others, leads him to a final moment of contemplation on a wintered shoreline some months later. Jean’s inability to exist after the incident is the film’s final tragedy. His death comes as quietly as the snow that fell on the school that day, and is the only offering of catharsis.

Incendies is, at its heart, is a mystery-thriller that finds its stage in an unspecified civil war in the Middle-East. The two main characters, twins Jeanne and Simon, are on the hunt for their father and brother as requested in their late mother’s will. They had been raised believing their father was dead, and the existence of their brother was similarly unknown until the reading of the will. It is these revelations of lineage, poisoned bloodlines and the senseless horrors of war that make Villeneuve’s breakthrough feature so compelling and devastating. No scene is more frightening in its implications than when Jeanne and Simon discover the truth about their father/brother. As Jeanne and Simon, in the present day, slowly piece together the puzzle of the past, the tragedy of Villeneuve’s film becomes almost unbearable. “One plus one makes two, it cannot make one,” is Simon’s reasoning to Jeanne when they sit alone in a hotel room. “One plus one, can it make one?” Villeneuve wants us to see clearly how fragile the human mind is, to lose sight of what we know and have it replaced with implacable darkness.

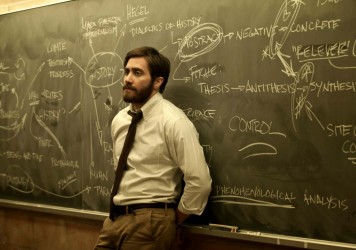

This art-house work of voyeurism, doppelgängers and schizophrenia is Villeneuve’s strangest, most ephemeral film to date. There is little within the urban, clinical existence of lecturer Adam Bell’s (Jake Gyllenhaal) life to warrant distinction but as the film – and his mind – unravels, Enemy becomes a dark commentary on the easily-blurred borders of personality. At the end of the film, Adam, struggling to place his existence after discovering a man who is physically identical to him, walks slowly down the hallway of his counterpart’s house. Why is he there? Why is he about to go to bed with the wife of a man who looks exactly like him? Why, when he beholds a giant, cowering tarantula in the corner of the bedroom does he look on with passivity, almost boredom? Gyllenhaal’s brilliant performance is a study in complexity, as Villeneuve shows us how a broken psyche can reform with key parts missing.

Hugh Jackman’s outstanding performance in Prisoners is drawn from the helpless, desperate Keller Dover who is slowing coming apart after the kidnapping of his daughter. The only lead in the case, the reclusive, mentally handicapped Alex (Paul Dano), becomes Keller’s dark obsession. He stalks him, imprisons him in an abandoned house on the edge of town, and plunges the depths of human depravity. Franklin, his neighbour whose daughter went missing alongside Keller’s, is coerced by Keller’s sick, beguiling logic that hurting Alex is their only chance to get answers. Franklin’s collapse is visible both physically, in the way he holds himself and struggles to maintain Keller’s gaze, and mentally via his confession to his wife. Villeneuve asks the age-old rationale of the troubled: can eye-for-an-eye justice ever be justified?

Emily Blunt’s dutiful, virtuous FBI Agent Kate Macer is in the throes of PTSD by the end of Villeneuve’s 2015 crime-thriller, having seen IED-rigged corpses in the walls of a cartel safe house, a violent shootout on the bridge into Jaurez, and a skewed perception of morality via the film’s very own Colonel Kurtz – Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro). It’s in the closing moments of Sicario, however, when Villeneuve makes us question authority, the law, and how closely justice and revenge sit on the judicial Venn diagram. Kate holds a gun over the balcony, knowing that a single pull of the trigger will throw her to the same demons that claimed the hearts of those she fought against and alongside in Mexico. But knowing the trauma she has endured, the audience readies itself for the report of gunfire. They almost invite it.

Published 7 Nov 2016

Jake Gyllenhaal sees his double and enters a vortex of wanton weirdness in this cold, experimental drama.

Harrison Ford is set to reprise his role alongside Ryan Gosling in the long-awaited sequel.

By Vadim Rizov

Emily Blunt gets a tough lesson in Mexican-US politics in this visceral drugs war drama from Denis Villeneuve.