Words

Jack Godwin, Gabriela Helfet, David Jenkins, Elena Lazic, Manuela Lazic, John Wadsworth

Illustration

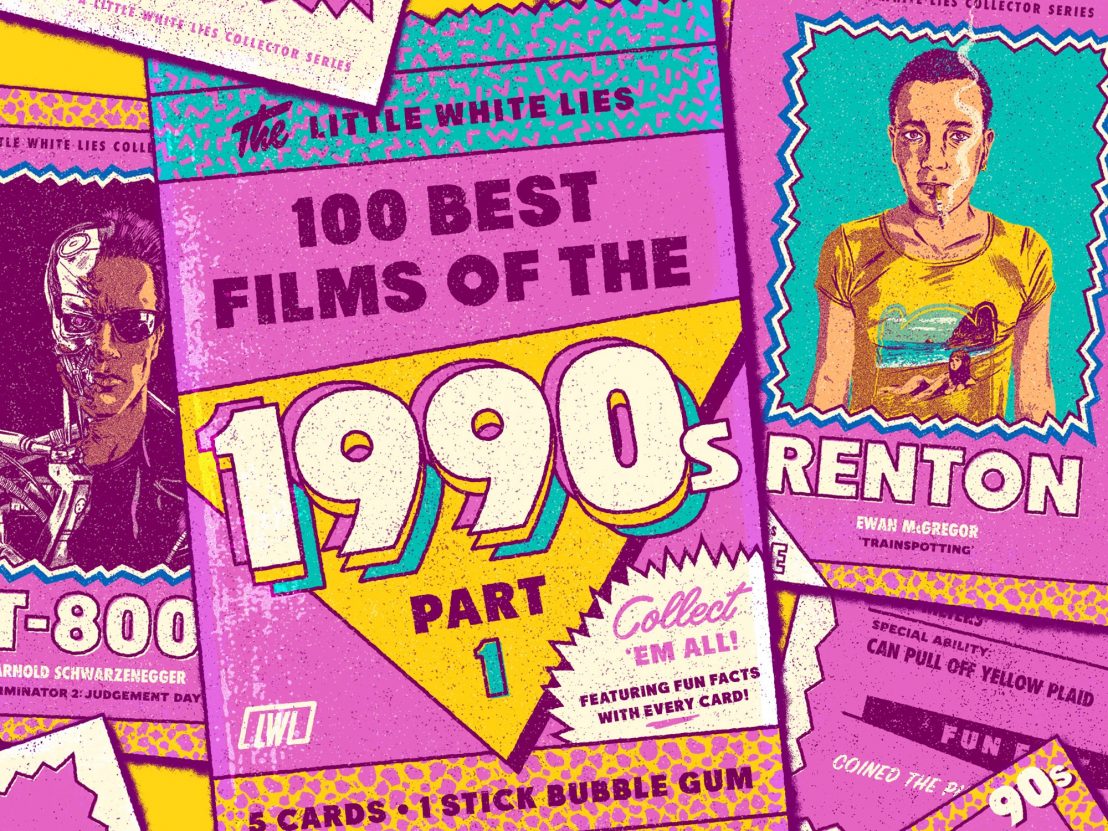

Our ’90s countdown kicks off with movies from Tim Burton, David Lynch and Hayao Miyazaki.

After you’ve read through this part of our 100 best films of the 1990s ranking, check out numbers 75-51, 50-26 and 25-1.

Nostalgia is a bitch. Barely a day goes by without some smackdown or other being issued across social media for the crime of looking back fondly at the 1990s. Yet from where we currently stand, 17 and a bit years in the clear, you really get a sense of an era of bountiful cultural riches.

The decade gave birth to some supreme talents, from Paul Thomas Anderson to Quentin Tarantino and Wes Anderson. Yet in compiling this survey we’ve chosen to pay tribute to both canonical classics and lost gems – the films we love, and the films we should maybe love a little bit more. And some, hopefully, are masterworks from the outer fringes of cinema that some may have yet to discover at all.

The running order of this list was formulated by committee rather than a drawn-out ballot process, and the choices represent a tiny clutch of the films adored by the LWLies team. For the most part we’ve limited it to one great film per director, so if a personal favourite of yours is missing, that’s probably the reason why. From a bomb-strapped LA commuter bus through to a tender gay romance set in the African desert, here are the 100 best films of the ’90s.

Alongside the criminally underrated biofuel-based thriller, Chain Reaction, and Kathryn Bigelow’s skydiving crime caper, Point Break, Jan De Bont’s Speed stands out in Keanu Reeves’ rich filmography as being among the most straightforwardly ’90s of action capers. A paper-thin premise – a bomb aboard an LA city bus will explode if the vehicle travels under 50 mph – and scant characterisation ally with spectacular stunts to deliver some of the most entertaining, brainless fun the aesthetically overblown decade ever had to offer. In the role of the young cop charged to save the day, the slender and androgynous Reeves introduced a new kind of action hero to a genre dominated by perma-jacked macho men like Schwarzenegger and Stallone. Elena Lazic

Maybe not quite a documentary, maybe not quite a fictional tableaux feature and maybe not quite an essay film, Patrick Keiller’s stellar whatever-it-is probes into England’s capital city with numerous eccentric modes of inquiry. Paul Schofield’s dryly intoned narration arrives over static landscape scenes which seek to exhume the ghosts of a city in flux, offering an arcane cultural history of a landscape that manages to be both vividly colourful and depressingly quaint. This was the first in a trilogy of films (alongside the similarly great Robinson in Space and Robinson in Ruins) which really put the psychogeographic form on the map – that is, the study of specific locations as viewed through the opaque prism of time and space. It’s a breathtaking work, both in originality and insight, and deserves its place at the table of great British films. David Jenkins

Emir Kusturica was once thought of as the Serbian sorcerer. His name conjured thoughts of power and creative eminence when spoken during the ’90s. But the hits and the mojo seem to have dried up this millennium. Still, we have his bombastic (and then some) 1995 take on the violence that naturally comes from enforced geopolitical division, all delivered under a blanket of cranium-pounding Klezmer sounds. The film opens on the bombing of a zoo, and only gets more nutzoid from there. The idea of a nation crumbling to dust and being hastily reformed is presented through the combustible companionship of Blacky (Lazar Ristovski) and Marco (Miki Manojlović), and the film’s only moment of relative respite comes with its breathtaking final shot. DJ

If you ever read critiques of films by the South Korean auteur Hong Sang-soo, chances are there will be references to young people getting blind drunk and engaging in awkward, fleeting love affairs. It’s quite remarkable that by the time of his brilliant second feature, all of the traits he would go on to develop as a filmmaker are present and correct. You might even see this movie as the director’s cinematic cornerstone, with all subsequent work a subtle, humorous or provocative variation of this deceptively simple romantic diptych. DJ

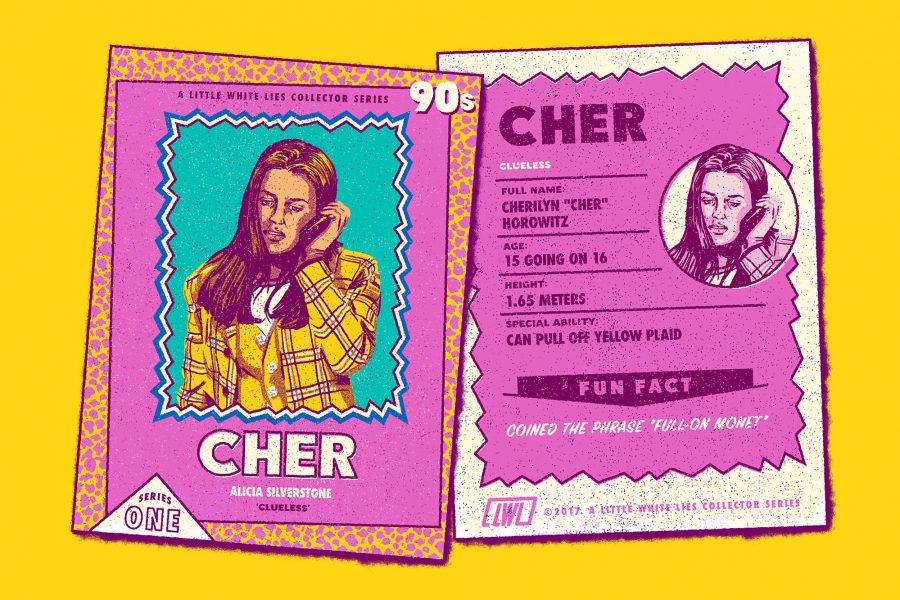

Not just the ’90s, Amy Heckerling’s satirical and enlightened reinterpretation of the teen movie genre is a joy for all times. Sixteen-year-old Cher (Alicia Silverstone) may at first come off as your typical WASP teenager – blonde, privileged and lazy. But Heckerling, with curiosity and compassion, looks past the clichés to reveal a sensitive and good-hearted girl. Though Cher’s attempts to use her advantages to help others can be callous, they nonetheless remain the genuine efforts of a young woman clueless about both her position and her own potential, which Josh (Paul Rudd) can clearly perceive. As she realises her mistakes and adapts to shifts in circumstance, Cher doesn’t so much change as she fully becomes herself. She still loves clothes and popularity, just more so. Manuela Lazic

Fred Madison likes to remember things his own way, “not necessarily the way they happened”. As if granting his wish, David Lynch holds the reality of his character’s world at arm’s length. Painful truths are heard through intercoms and traumatic events are alluded to or glimpsed through a television screen. Piecing together the narrative hidden beneath may be a strenuous task, but it’s clear that this master director is more interested in examining the paranoia and insecurity that twists Fred’s mind down a path of violence, and the denial necessary to live with it. Lost Highway is one of the most unsettling, psychologically complex films ever made, a riveting journey into the dark recesses of masculinity. Jack Godwin

The Iron Giant stands as an inventive hybrid of gorgeous hand-drawn and CG animation, just as the latter was beginning to rule the creative roost. Its widespread acclaim from critics didn’t save it from underperforming at the box office, yet while countless efforts from this era are now forgotten, The Iron Giant is remembered for its Cold War setting and emotional potency. Simple themes of peace and friendship are expanded into a reflection of humanity’s self-destructive cycle of violence, as an innocent refuses to be the weapon that others insist he is, warming and breaking our hearts in the process. JG

Following his biggest, funniest film – 1989’s loopy rock ‘n’ roll satire, Leningrad Cowboys Go America – Finland’s Aki Kaurismäki went very dark in this tragic fable of a humble female factory hand who is tipped over the edge by the twin evils of capitalism and the male species. The director’s regular leading lady, Kati Outinen, is the sad-eyed nucleus of this shocking film, and her deposits of howling rage are masked behind a poker face that just makes you want to burst into tears. It’s perhaps something of an outlier in the director’s offbeat back catalogue, almost Biblical in its moral simplicity and also a film which dares to depict crushing depression as no laughing matter. DJ

With the rise of VHS and television, the ’90s saw the beginning of a real exchange between older high art and brand-new pop culture. The Mask may technically be a comic book film, but teenage spectators might not get all its jokey references to classic cinema. But there’s something for everyone, though: when Stanley (played with controlled insanity by Jim Carrey) wears that mask, he literally becomes a cartoon character, distracting his opponents with gags enhanced by early CG morphing. There’s even a sexy lady (Cameron Diaz in her first role) and a clever dog. The moral tale behind The Mask may not be very profound – Stanley is great au naturel – but its energy and demented aftertaste make it just so irresistibly ’90s. ML

No one has ever said that being in a band was easy, but this 1991 film by Alan Parker captures both the euphoric highs and blood-and-vomit-laced lows that come from collaborating in the name of making sweet music. Fed up with his lowly economic lot, feisty Dubliner Jimmy Rabbitte (Robert Arkins) decides to assemble a gigantic soul review group and transport them to unlikely stardom. Based on a novel by Roddy Doyle, it focuses on the tragedy of individualism when it comes to the search for more profound collective truth. When these talented players are consumed in song, they’re absolutely unstoppable. The problems start when the music stops. DJ

It only seems fair that Wesley Snipes crops up at least once in this list. We could have opted for his stellar turn in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever, or when he played the smartest of smart-mouths in Ron Shelton’s White Men Can’t Jump. But we retain a lot of residual love for Nino Brown, the neatly turned-out crack dealer he essayed in Mario Van Peebles grim portrait of drug culture in New York City. It’s a film about the fall-out of the coke-fuelled ’80s, charting a nouveau riche uprising within the narcotics trade in which housing tenements become urban fortresses in which economic supply and demand is carried out with brutal efficiency. As dour as the subject matter seems, the film is lively and dramatic, attuned to the nuances of street culture and the idea that, just maybe, these evil men praying on the lives of addicts are merely in a fight for their own survival. DJ

12 October, 1993. Seventy-two days from now, a teenage student will kill three people then commit suicide. Detached fragments document the lead-up to the crime, and we watch as if flicking through facts in a case file. A young Romanian migrant and thief sleeps on the streets of Vienna. A shy foster child fails to warm to her prospective parents. A bank employee is visited on the job by her father. Some of the clips last five seconds, others five minutes. All share a sense of underlying tension. As the characters head for disaster, excerpted newscasts remind us that the impending tragedy is just one in a world of many. John Wadsworth

Growing up can be a particularly disheartening experience for those who refuse to compromise. Hal Hartley’s little gem from 1990 follows two such people as they struggle to get free, surrounded by others whose ‘responsibilities’ have made them neurotic, selfish, jealous and cruel. Yet for a film populated with such sad characters, Trust remains incredibly exciting and funny. The sheer energy of the two leads (Adrienne Shelly and Martin Donovan) is echoed in the unwavering invention and beauty of the direction, which recalls Steven Soderbergh’s masterpiece Sex, Lies, and Videotape in its experimentation and focus. The film’s distinctive quirkiness and zippy dialogue make it a true classic of ’90s indie cinema. EL

This delightful moral fable about a tenacious seven-year-old girl trying to convince her mother to buy her a goldfish mixes the harsh realities of modern Tehran with a multi-tiered adventure yarn that harks back to classical fairy tales. In amateur actress Aida Mohammadkhani, director Jafar Panahi discovered the perfect knee-high lead, as she discovers just how hard it is to be able to spend your hard-earned money without being sidetracked or scuppered at every circuitous turn. The film’s unadorned simplicity when it comes to the characters and situations allows it to work on a deeply symbolic level, the balloon of the title eventually being revealed as an emblem of pleasure, peace and political accord. DJ

Nearly 50 years into his career, nouvelle vague titan Claude Chabrol was still proving that he could knock a film together. Sophie (Sandrine Bonnaire) is a maid for a wealthy household in Brittany who finds an unruly companion in Jeanne (Isabelle Huppert), the village postmaster. The two bond over mischief, implied violent pasts and haughty bourgeois types, yet the exact nature of their relationship is withheld. Chabrol revels in the ambiguity, denying us the formality and order suggested by the film’s title. Sophie and Jeanne are not cardboard cut-outs spurred on by class conflict alone, though. While they share a refusal to submit to subservience, their precise thoughts, feelings and motives remain tantalisingly uncertain. JW

The residents of the post-apocalyptic apartment block in Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s grotesque comedy, Delicatessen, start their tenancy in hope and conclude it as the key ingredient of a bourguignon. The latest victim-to-be, a former clown called Louison (Dominique Pinon), entertains two of the flats’ inhabitants with cello-and-saw duets and bedspring-led choreography, absurdist excursions that distract them from the horrors at hand. Viewers take refuge, meanwhile, in neat technical tricks and pitch-black humour. The opening scene sets the precedent for both, with the camera lens gliding into the darkness of a dank drainpipe, which carries the sound of knives being sharpened from predator towards the quaking prey. JW

Any conversations addressing the notion of the noble folly in cinema absolutely, positively must pay lip service to Les Amants du Pont Neuf by Leos Carax. Wildly ambitious, endlessly dynamic and with stores of passion to burn up like so much cheap booze, the film capped the swift ascent of its decadent creator by becoming a logistical nightmare to shoot and an eventual bomb at the box office. And yet, its story of wild love between a transient circus performer (Denis Lavant) and a painter who is gradually going blind (Juliette Binoche) is exhilaratingly romantic, even if it does occasionally push things deep into the realms of visual and emotional histrionics. Once seen, however, it’s never forgotten. EL

Soulful animation is what Hayao Miyazaki does best, and Porco Rosso follows a storied World War One fighter pilot who, courtesy of a spell, gets transformed into a pig. Not ideal. While the film may seem like a familiar storybook tale of a character forced to come to terms with his new, un-human appearance, its beautiful, watercolour animations are so immersive that the magical Studio Ghibli world you’re experiencing feels as real as any earthly 3D counterpart. This is largely thanks to Porco Rosso’s breathtaking flight scenes, which lift the movie from pretty illustrations into a true, undisputed work of art. Gabriela Helfet

Cathy Burke picked up the best actress prize at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival for her superlative turn as a domestic abuse victim in Gary Oldman’s sole directorial effort, Nil By Mouth. It’s sad to think that neither Burke nor Oldman ran with their successes, she seldom starring in “serious” cinema again, and he never heading back behind the camera. Yet the film remains one of the decade’s high watermarks of British-made cinema, an unflinching portrait of how substance abuse tears families apart that never resorts to cheap moralising or sentiment. Wideboy Ray Winstone is a force of nature as the vodka-swilling patriarch with a wicked temper, but it’s Burke as his doe-eyed punching bag wife who steals the show. Also one of the great London movies. DJ

This deathsong fantasia in which a son cradles his mother as she slowly passes from one life to the next is the film that announced the illustrious talents of Russian director Aleksandr Sokurov to the world. It’s a gleaming cine-fugue which encases poetic rumination and idealised, purified romance into a deceptive realist shell. Maybe not a movie for cynics who envision death as just another tick on an infinitely-sprawling spreadsheet, this instead taps into and visualises interior desires and dreams of how we would perhaps like to go. The son treats his mother to a slow-motion whirlwind tour of the surrounding landscape, allowing her to physically experience the natural elements as a sublime parting gift. To quote Nick Cave: “I wept and wept, from start to finish.” DJ

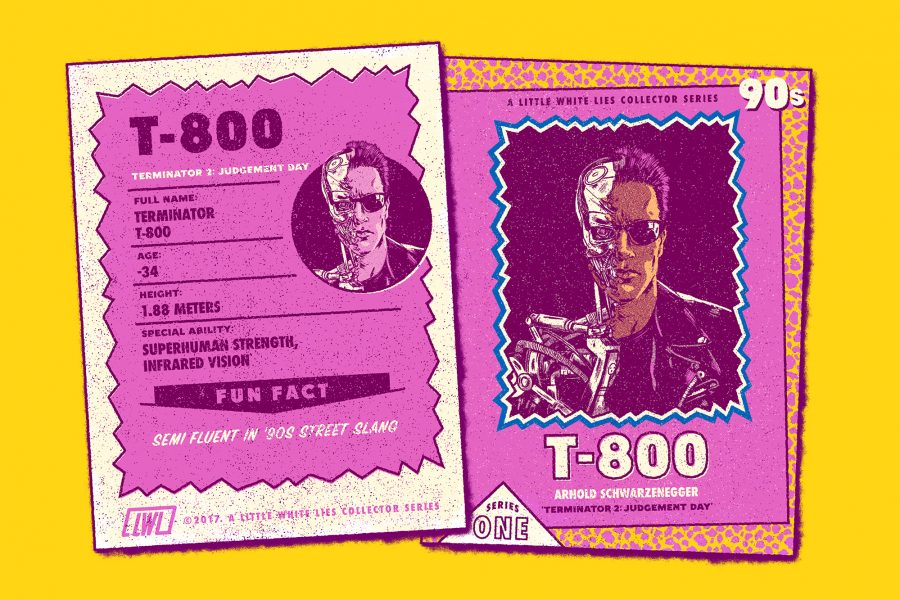

In The Terminator, the relentless stalker of nightmares was brought to life in an age of burgeoning technological advancement. Seven years later, director James Cameron returned to the scene of the crime to create a follow up that is not only an inventive fusion of science fiction, horror and action, but a pivotal film in the evolution of the blockbuster form. Sarah Connor struggles to bring up her son, grieving over the death of his father and the inevitable extinction ahead. With this at its core, Terminator 2 has the basis to support its exhilarating escalation of intense confrontations between Arnie’s reformed cyborg and the iconic liquid metal ferocity of the T-1000. JG

Tim Burton’s macabre fantasy worlds have always celebrated those who mainstream society might call freaks because of their outward appearance. Edward Scissorhands takes this idea to an extreme, telling the story of a man-made, human-like creature who has scissor blades in place of hands. Instead of letting Edward turn into an on-screen caricature of an outcast, Johnny Depp brings to him a remarkably delicate otherworldliness. As this ‘don’t judge a book by its cover’ fable soon blossoms into an unlikely love story, it remains enchantingly strange until the very close. GH

Prior to Catherine Breillat’s Romance, sex movies were intended as either light, soft-focus titillation for couples or agonising philosophical treatises which did everything in their power to dull any glimmer of eroticism. Here, we get the best (and worst!) of both worlds, as the director follows Caroline Ducey’s Marie on a private sexual odyssey spurred on by the fact that her boyfriend can’t and won’t make love to her. The learning curve is steep, and with each new nighttime sortie she breaks through a new pleasure threshold, but always remains mindful of the power relationship involved in each causal tryst. What makes the film special is that Marie is driven by credible human impulses and is not just a symbolic excuse for hardcore imagery to be regularly catapulted towards the lens. DJ

It’s wonderful to think that Canuck conjurer Guy Maddin has tended his lone field of rare herbs and flowers right from day one, and 1992’s batshit chimera Careful remains the apotheosis of his singular craft. It’s essentially a deadpan comedy but with overtures of high seriousness, drawing on the classic, middle-European “mountain” film but going hogwild with this austere template. The film is set in the fictional snowy berg of Tolzbad, a place which is constantly under threat of destruction by avalanches. As a precautionary measure, loud noises and emotions are forbidden lest they get everyone killed. That the result is even more preposterous and precarious than the logline would suggest stands as testament to this brilliant director and his extraordinary vision of cinema. DJ

Trainspotting is a vision of Scots getting “mad wae it” that’s purer than a fresh kilo of Colombian chang. It’s aggressively disgusting, aggressively surreal, aggressively mesmerising, aggressively funny, aggressively sonic and aggressively one-of-a-kind. Danny Boyle’s finest also holds the title of most perfect music use in a film, possibly ever. It follows a crew of hipster drug addicts, and and even in their most revolting, truly vile moments (see Renton’s faeces plunge or Spud’s kitchen sheet horror show for a primer) we end up feeling deeply for these wreck heads. On the outside they’re druggies, but what lies inside their skag-tinged hearts? They’re the same – albeit far more entertaining – as a group of IT geek pals whose idea of having it large is winning their local pub quiz. GH

Now read numbers 75-51Published 15 Mar 2017

The cult director’s peek behind the curtain of this iconic American city reveals the horrors within.

The legendary Studio Ghibli director is reportedly working on a new feature-length project.

The master of the macabre hit his creative peak with this singular suburban fairy tale from 1990.