“Dick Laurent is dead.” These are the first words Bill Pullman’s character hears in Lost Highway, and his nervous response hints to some subconscious understanding of the seemingly random message. The voice speaking the words is coming through his home’s intercom system, and a quick look out the window shows no signs of anyone outside. A disembodied voice, a protagonist who seems to haunt their home rather than live in it, a foreboding sense of unease – this film has David Lynch’s strange fingerprints all over it from the start.

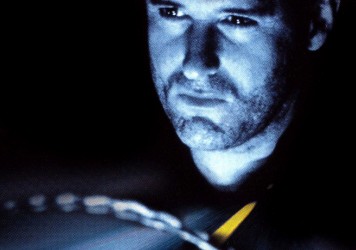

For many, the director’s 1997 psychological thriller serves as a prelude to his 2001 masterpiece Mulholland Drive, but it is a mysterious, enthralling neo-noir in its own right. Briefly put, Lost Highway tells the odd tale of Fred Madison (Pullman), a saxophonist in the sleazy night-time world of Lynch’s eerie, twisted California, who mysteriously finds himself on death row for the murder of his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette) despite having no knowledge of her death. While on death row, he inexplicably morphs into Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty) and begins leading a completely different life.

Mulholland Drive perplexed and entertained in equal measure before offering some measure of catharsis by its conclusion, but Lost Highway steers us firmly down the road away from rational thought. Madison’s visions of strange figures driving down deserted roads, and of a pale man who seemingly knows everything about him, typify the Lynchian desire to disrupt small-town America and replace it with a mirage.

Lynch’s idiosyncratic use of Los Angeles’ iconic topography, with its distinct streets and sloping hills imbuing his vaudevillian freak shows with different kinds of evil, is as compelling in Lost Highway as it is in Mulholland Drive. And then some. Robert Loggia’s angry, mercurial gangster, Dick Laurent, is a menacing force that holds the sunset strip on a string – in one of the film’s best scenes, he nearly drives a tailgater off the hillside and drags him out of his car in a vulgar, aggressive show of machismo. LA gets under the skin of Lynch’s characters; they bear its secrets like a criminal Atlas.

When Laurent shows up at Pete’s car garage, it’s hard to deny the influence that found its way into Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, with its Hollywood Hills backdrop, blue-collar shop fronts and other recurring motifs. Both films follow morally dubious characters as they navigate a nonlinear, largely nocturnal world. It’s this dream-like setting that seems to have crept out of the Black Lodge itself, one which Lynch was keen to return to after the critical failure of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. The mysterious pale man at the centre of Lost Highway embodies much of the horror present in Twin Peaks, and marks a coming together of Lynch’s folkloric parallel worlds, haunted towns and nameless spectres.

Though not as universally lauded as Blue Velvet or Lynch’s other LA neo-noir, Lost Highway deserves to be spoken of in the same breath as the cult director’s best work. So before Twin Peaks returns for its third season and the world falls at the feet of this surrealist master, perhaps you should take the first exit and head into the hills. Go get lost, again.

Published 22 Jan 2017

By Tom Watchorn

Paranoia, mystery and moral ambiguity abound in David Lynch and Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpieces.

By Ed Gibbs

The cult filmmaker shares stories and archive from his childhood, while still managing to remain as elusive as ever.

By Lara C Cory

The Trent Reznor-produced score is being reissued for the fist time in 20 years.