Alfonso Cuaròn’s monumental love poem to Mexico and the woman who made him a man.

Let’s open on a question, a pretty hefty one all told: what is cinema? It’s sound and images and edits and actors, but what is its purpose, its wider function, its place within the ecosystem of art? Some movies can be seen as dreams made manifest, a portal into a realm of subjective fantasy. Movies can be political tools, whose purpose is to teach or convince the viewer of what the makers believe to be a rational viewpoint. They are lessons to be learned, repeated and occasionally dismissed out of hand. There are movie artefacts which calcify a moment in time, whether through their formal innovations, their ideological leanings, their tone or their character.

Or maybe they were inbuilt with a rapidly diminishing half-life. I think movies are at their most beautiful when they tap into personal memories. And not just anecdotes about people, or tall tales rehashed and retooled, but when they mark a sincere attempt to bring a credible vision of the past to life. Maybe you could see this as nostalgia without the sentiment, or an attempt to give equal weighting to both context and subject. As viewers, we can only accept what we’re being shown and attempt to deduce whether it is a crude manipulation of reality, or something more honest.

To watch Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma is to see a man scouring the archives of his mind. This is film as a voyage of discovery. Each image feels like the result of synapses firing, of deep research, of conversations and connections and naked self-expression. The key to its greatness is that Cuarón eliminates any sense of narcissism. He silences the showman inside him. In past triumphs like Gravity, Children of Men or even Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Cuarón has been happy to leave the gorgeous smudges of his fingerprints on the work.

Here, he does everything in his power to retain a pristine purity. The film is set in Mexico City and its environs during the early 1970s. It opens on a long, top-down shot of some floor tiles. They look like a mass-market product, not some gorgeous, artisanal antique. Water washes over them as a bucket is emptied outside of the frame. Nuggets of glass set within the tiles start to twinkle and their overall shape distorts. Memories fade in and out of focus. The tiles are an important introduction to the family with whom we about to spend the next 135 minutes. If the tiles were wrong, the film would be wrong. This isn’t a film about tiles, it is about what it means to get the tiles right. It’s domestic poetry, and all in homage to a place that exists only as scattered, internalised images.

Cuarón strives to make this story feel like a journey back in time, but without resorting to formal clichés. It doesn’t follow a traditional three-act structure. It piles on detail that might seem extraneous, but is actually vital and comforting. It helps to create the illusion of an all-enveloping experience. One key sequence drops in on a vital romantic clinch which takes place in the smooching seats of the local picture palace.

The first run attraction, visible in the backdrop, is Duccio Tessari’s screwy, shrill heist picture, The Heroes, which sees Terry-Thomas, Rod Taylor and a buxom nun crushed into the cockpit of a fighter plane as cross-eyed Nazis take pot shots from below. There’s a comic disparity between the seriousness of the whispered conversation between our soft-spoken heroine, Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio), and the amorous rogue she is with, Fermin (Jorge Antonio Guerrero), and the lunatic antics on screen.

It’s an incredible sequence, one which cross-processes public joy with private agony. Fermin scarpers and Cleo is left to tip-toe from the cinema in a lucid daze (anticipating our own experience when Roma ends). She is met with a carnival of wailing families, toy vendors, musicians and street barkers. From her gaunt expression, she is in an empty room, alone with her thoughts. A simple, brilliant tactic that is used in pretty much every scene of the film: highlighting the tension between foreground and background.

The film, in its entirety, charts a tumultuous year in Cleo’s life. She is the person who is throwing water over the tiles, cleaning them so her employers don’t have to navigate an assault course of dried dogshit as they enter and exit their spacious townhouse. Her maid’s quarters are situated out back, but she is no social outcast. Matriarch Sofia (Marina de Tavira) treats her problems seriously and understands that she is the glue that binds the family together.

Cleo travels with them on their Christmas break and later on a beach holiday. A theme of dangerously unreliable men is floated early on, as the clan, which includes four young children, is knocked off its stilts when father Antonio (Fernando Grediaga) walks away from his responsibilities. On order to reconnect with his lost youth, he literally chases younger women and takes up scuba diving.

All the dramas, traumas, tantrums and tiaras of family life are laid bare, but Cuarón avoids trying to guess how these minor daily ructions make people feel. This is something that stretches beyond his remit as an archivist. He achieves this by filming scenes at a humane remove. The camera arcs across the chosen space in a panoramic arc. It’s locked to eye level for much of the film. It occasionally feels as if the director has sent a probe back in time to capture how we once lived. It makes the emotions feel more genuine, almost like they would be seen in a documentary. The dialogue, too, is purely naturalistic and contains no “lines”.

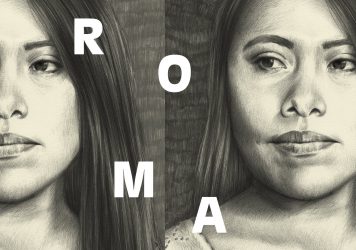

This is Cleo’s story, but she is framed as a figure in the landscape, as a woman who is bobbing on the tide of history. It’s hard to describe Aparicio’s performance as anything other than miraculous – she manages to embody a person accepting of her lot, trapped between classes and cultures, but utterly fearless when it comes to protecting those she loves. Just as Cuarón himself attempts to attain some semblance of anonymity from behind the camera (he acts as his own cinematographer), Cleo is driven by a selflessness that is part of her muscle memory. Her sense of goodness exists outside the realms of moral relativity.

It may seem problematic for a man to make a film about how men are unable to comprehend the labour of motherhood, but Roma feels like a continuation of a conversation that Cuarón has been engaged with for many years. In Children of Men, childbirth has become obsolete and humanity reverts to end-of-days savagery. Gravity offers an ornate allegory of the birthing process in the form of a woman making a daring, skin-of-her-teeth return to Earth from outer space.

Roma is his most direct and politically nuanced take on questions of what it means to have children and the evanescent fragility of life. In one sequence, Cleo is sent to a labour ward having just discovered that she is pregnant. She quietly surveys a room full of wriggling newborns, then something happens which compounds the reality of her situation in an instant. In its majestic, intuitive sweep, Roma is a film which deals with the responsibilities we take on – sometimes by choice, sometimes not – to nurture the next generation. It’s about that choice, too, and about the torment caused by having responsibility foisted upon us.

Within Cuarón’s career, it doesn’t feel like there was a precedent for this film, but at the same time it makes total sense. This is his magnum opus, unassuming, emotional, never melodramatic and sublime in its scope and commitment to detail. It is a love letter to friends, and a new way of looking at the past on screen. It stands as testament to the awe-striking complexity of humankind.

Roma is released in Curzon cinemas 30 November and on Netflix 14 December. Read more about the film in our latest print edition.

Published 30 Nov 2018

Excited to see what Alfonso Cuarón is up to, but this one has largely dodged the hype machine.

Well blow me down with a feather. An astonishing work.

Cuarón’s masterpiece. An artwork that towers above the pretenders.

Our latest print edition pays tribute to Alfonso Cuaròn’s personal ode to movies, Mexico and the woman who made him a man.

By Luke Walpole

Alfonso Cuarón’s film was released in 2006 and is set in 2027, so why does it feel so relevant today?

The trailers were right for once – Alfonso Cuarón’s disaster movie set in space is one of the year’s best.