Pyrokinetic mutants, shirtless firefighters and eco-fascists collide in the first feature film from Studio Trigger.

An exciting cacophony of flames, robots, chiselled torsos and ridiculous catchphrases from its first five minutes, Promare is a near-perfect distillation of the frantic, hyperactive and elaborate work of Hiroyuki Imaishi. Elements of the Studio Trigger co-founder’s past work are ubiquitous, like Shigeto Koyama’s character designs ripped straight from Gainax’s Gurren Lagann, and the balance of comedy and wild, borderline deranged action of Kill La Kill.

In the world of Promare, part of the population has a mutation called ‘Burnish’, giving them power over otherworldly flames. The emergence of this mutation led to a worldwide calamity known as the Great World Blaze. Cut to 30 years later, and a group of mutant radicals known as the Mad Burnish are setting everything aflame, with the team of firefighters Burning Rescue there to put the fires out.

Chief among them is the film’s boneheaded, persistently shirtless protagonist Galo Thymos – self-described as “the world’s number one firefighting idiot” – who loves the sound of his own voice as much as he loves saving the world, yelling meaningless catchphrases (“It sets my firefighter’s soul ablaze!”) while he does it.

The mix of self-aware banter and exuberant action is intoxicating, a hypnotising tornado of bright geometric patterns, pastel-coloured flames and swooping 3DCG shots engineered to fit with the more traditional 2D animation. It’s almost a seamless merging of two fairly distinctive animation styles, though you can still track the breaks between the two methods. Beyond the action, the repetition of triangles in the souls of the Burnish and in the flames enforces the idea of the spiritual connection between these people and the planet, entirely through visual design.

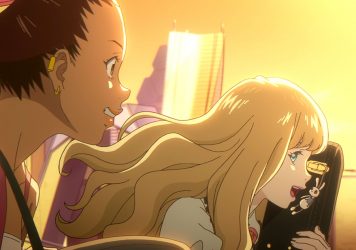

Across the narrative, Galo fosters a relationship with his foe turned frenemy Lio Fotia, the young leader of the Mad Burnish. With Lio, Imaishi plays with the X-Men dynamic of persecuted super-beings, and even calls on the idea of eco-facism for its primary antagonist, who experiments on this minority for the supposed betterment of a dying planet. As Imaishi pulls out some bonkers third-act surprises, Galo’s understanding of the world is turned on its head. This comes with a surprising tenderness and sentimentality, as the Burning Rescue’s accomplishments are put into perspective and the persecution of the Burnish is revealed, after which the real story – the liberation of Lio and his people – begins.

The ecological and ideological issues at the heart of Promare are eventually resolved by keeping true to one’s self, and by the good-old shōnen anime logic of just punching harder than you ever have before. Imaishi is fully aware of this absurdity, and owns it with a bombastic swagger. Ultimately, the style is the substance, the motion is the motive – and the film’s greatest pleasures to be found in its sound, fury and purely expressive chaos.

Published 25 Nov 2019

Can Imaishi translate the energy of his television shows to film?

Absolutely he can.

As delightful as it is demented.

The latest anime series from Shinichirō Watanabe is among his kindest and most soulful to date.

Director and designer Shōji Kawamori sees hand-drawn animation going the way of noh or kabubki in Japan.

Shinichiro Watanabe’s singular ’90s show is yet another classic anime that should be left well alone.