A humongous creative undertaking and a simple love of dogs combine for the most staggering achievement of Wes Anderson’s career.

A small bronze statue of an Akita stands at one of the five entrances to Shibuya Station in Tokyo, serving as a popular meeting spot and point of interest for the thousands of visitors who pass through each week. This particular Akita, who is immortalised in precious metal, has a name and a history – Hachikō, the dog who patiently waited nine years on this very spot for a master who would never return. He may have passed away some 80 years ago, but the tale of the dog who waited continues to enchant and inspire folk the world over.

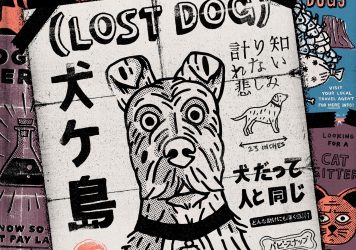

In his new film Isle of Dogs, it seems that Wes Anderson has spun a similarly wistful yarn about about the strangely transcendent power of canine companionship. Anderson likes to frame his films as tall tales, placing viewers at a gentle remove from reality to a plane of existence more fantastic and charmed than our own. His latest is no exception, a fastidious visual ballad prefaced by an exquisitely-detailed prologue that provides some quick but necessary exposition, reminiscent of the breathtaking, ‘meet the family’ opening to his 2001 commercial breakthrough, The Royal Tenenbaums.

The mythology of Isle of Dogs informs of the cat-loving (evil) Kobayashi dynasty and a mysterious outbreak of ‘snout fever’ which threatens the population (both canine and human) of retro-futurist urban prefecture, Megasaki. The solution presented by no-nonsense Mayor Kobayashi is to banish every dog to a floating, off-shore garbage dump named Trash Island. This reactionary decree does not go down well with his young ward, Atari, who promptly sets off to retrieve his pet dog Spots from exile – and in doing so, happens upon a rag-tag pack of self-styled alpha dogs.

Many of Anderson’s familiar wreckin’ crew lend their distinctive voices to these pups, including Edward Norton (Rex), Jeff Goldblum (Duke), Bill Murray (Boss) and Bob Balaban (King). It’s fitting, then, that Bryan Cranston plays the outsider among the outsiders, his gravelly voice bringing a soft edge of menace to stray mutt Chief, who is quick to warn those he meets: “I bite”. The dulcet tones of Courtney B Vance lends a pleasant gravitas to the film’s narration, but arguably the most fun comes with Tilda Swinton’s typically eccentric side-character. To describe her would be to spoil one of the film’s most charming surprises, but her inclusion is indicative of the thought that has gone into every tiny element of the film. With Anderson, nothing is left to chance – every breed comes with a backstory, just as every strand of fur is meticulously matted to enhance the film’s exquisitely scuzzy aesthetic.

There’s so much pleasure in the ambitious production design too, from the exquisite puppets and sequences influenced by traditional shadow play to animation inspired by Japanese woodblocks and Alexandre Desplat’s striking, non-orchestral score, which is fully in tune with the film’s setting. In a bold contrast from his previous work, Anderson only places a single ’60s pop song into the mix, The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band’s ‘I Won’t Hurt You’, whose sombre strains add to the film’s melancholic undertow.

In its design, Megasaki itself inhabits both past and future – it is an audacious study in Japanese futurism, and it’s easy to spot the influence of Hayao Miyazaki and Akira Kurosawa in the elaborate graphic animation sequences and the use of a soulful guitar melody borrowed from the latter’s 1948 noir Drunken Angel. Rather than feeling derivative, Isle of Dogs feels like an impassioned and sincere response to the work of these master filmmakers – what a treat it is to feel a director’s regard for his influencers so acutely, and to feel that Anderson has worked hard to ensure the product he has created feels authentic and respectful.

This is most evident in his decision to have Japanese characters speak in their native tongue, with swaths of dialogue going untranslated (as explained in a handy opening title-card). It’s a fascinating choice that means the film will be viewed entirely differently by Japanese speakers. Also, there’s being a playful sense of irony that comes from watching a film where you comprehend the dogs more than you do the human characters.

In contrast with 2009’s Fantastic Mr Fox, which blurs the line between animal and human, the dogs here are very much wild things, and the narrative is told largely from their perspective. Beyond a vague familial tradition, we never learn what it is that motivates Kobayashi’s hatred of dogs – because it doesn’t matter. After all, why should the reasoning of humans matter to dogs? Their chief concerns and motivations remain pleasantly animalistic – a warm bed, an attentive master and a plentiful supply of food.

As he did with the young, runaway lovers at the centre of 2012’s Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson indulges the unique perspective of his protagonists. While it’s a risk to centre a film so completely on characters who have such animal motives, it’s thrilling to see Anderson commit so completely to the world he has created – he trusts his audience, both young and old, to follow suit. It’s a deceptively simple story – like a lovingly crafted and hand-painted matryoshka doll, with each new lacquered layer a delight to unpack and behold. The narrative scampers playfully between Trash Island and Megasaki, like a dog attempting to follow two different scent trails, bounding with wide-eyed excitement when the paths finally converge.

This is also one of Anderson’s most surprisingly sedate films. It lacks the whirling hijinks of 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, and is perhaps most reminiscent of his early work in 1998’s Rushmore, down to its wry wit and a soulfulness that sticks long after the end credits have rolled. Yet it possesses the heart of a mighty beast. This love story is about the purest relationship that exists in the known world: that between a 12-year-old boy and his dog. In every one of his films, this singular director has demonstrated a deep capacity for human empathy, and it’s this element that comes across with the most force in Isle of Dogs.

A sense of understanding and admiration between human and canine that sinks into each immaculate frame. There’s some melancholy, too. For the love of a dog – unconditional though it may be – is only a fleeting gift, and it’s this heartbreaking detail which elevates the film beyond a simple (and simplistic) animal caper. It’s soulful, reflective poetry that’s etched on celluloid, and plays dividends by viewing on the biggest screen possible. It also invites (demands?) repeat viewings, so that like a dog proudly digging up the backyard in search of a juicy bone, you too might uncover something new each and every time.

Published 27 Mar 2018

More Wes stop-motion sounds like a dream... if he can do justice to the setting.

Surprisingly different from anything Anderson has done before. In a very good way.

Visually stunning, emotionally arresting, dog-gone brilliant.

Our latest print edition offers an exciting look inside Wes Anderson’s stop-motion opus.

By Luís Azevedo

A new video essay by Luís Azevedo explores this curious canine conundrum.

The US writer/director takes us inside his spellbinding stop-motion opus Isle of Dogs.