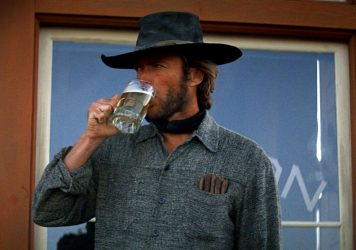

At 91, Clint Eastwood delivers a low-slung neo-western charmer about an old dude taking one final shot at redemption.

At a comfortable trot, Clint Eastwood has entered the “auteurists only” phase of his career. As with his last starring gig The Mule, his latest film Cry Macho is destined to draw a response divided between those who find leisurely-paced footage of an old man puttering around to be dull, and those inclined to take this same thing as a rewarding culmination of a six-decade career.

Viewers processing the new western ramble on its own terms may see a certain ridiculousness in the sight of a skeletal Eastwood punching out a gangster a third his own age, or romancing the much younger woman who finds him irresistible. The faithful, instead, accept this as proof that their guy’s still got it, the implausibility part of the charm.

As a director, he creates a reality in which he can continue being himself, though his recent films have excelled by pairing that with an awareness of his approaching obsolescence. Beyond the subjective interpretation spanning slog to masterpiece, the text conveys that this world will leave behind the kind of person Eastwood’s proud to have remained after all these years.

Rancher and erstwhile cowboy Mike Milo is alright with that, as he is with most things. (The trailer wisely used his instant-classic read of the line “If a guy wants to name his cock Macho, that’s okay by me” as its button.) In keeping with The Mule’s man-on-a-mission profile, he’s a cantankerous sumbitch with a soul full of regret and a heart of gold, his out-of-placeness in the world reflected in a Mexico where he stands out as a gringo.

He’s gone south of the border to retrieve his employer’s son Raphael (Eduardo Minett), in whom he gradually recognises a kindred spirit. He, the boy, and their rooster companion Macho have all been knocked around by life, which “Rafo” reacts to by trying to harden himself – a tactic that Mike employed long enough to know isn’t worth the loneliness. When he announces that much in near-explicit terms, the moment lands as blunt, perhaps heavy-handed. But there’s also an intense poignance in the knowledge that not so long ago, Eastwood could not bear to accept this idea.

That context makes all the difference between the perception of their journey back to the States as a slight, barely eventful road trip, versus an existential odyssey toward the final destination of inner peace. Mike and Rafo take one of their many pit stops in a village where Mike’s experience with animals ushers him into the role of de facto town veterinarian, a near-saintly Francis of Assisi-type post unfamiliar for the rough-hewn Eastwood. When the chase driving the film pauses for a moment so Mike can give a friendly scritch behind the ears to a roly-poly pig, audience perspective determines whether this is a revelatory glimpse of newfound softness or just tedious wheel-spinning.

Growth is only evident over time, a fact that many films condense to an arc fitting in the space of a couple hours or so. The current, likely final stage of Eastwood’s cohesive filmography delivers that same fulfilment on a far vaster scale, starting in the late twentieth century and running through the millennium. Unlike the many cinematic-universe-based franchises attempting to mount drama through multiple releases, Eastwood isn’t fixated on this grander continuity, allowing it to present itself organically rather than forcing it.

To say that he’s making movies for the fans and not the critics would be inaccurate twice over, both because many of his fans are critics, and because he’s only ever made them for himself.

Published 19 Sep 2021

Every new Eastwood film could be his swan song.

One last ride or not, a satisfying finality.

At 91, he’s still maturing.

This controversial 1973 western ranks among the director’s finest works.

By Mark Asch

Clint Eastwood directs and stars in this outstanding American road movie about an ageing drug runner.

By Adam Scovell

Compared to other films of the counter-culture era, Eastwood’s directorial debut looks at the darker side of Free Love.