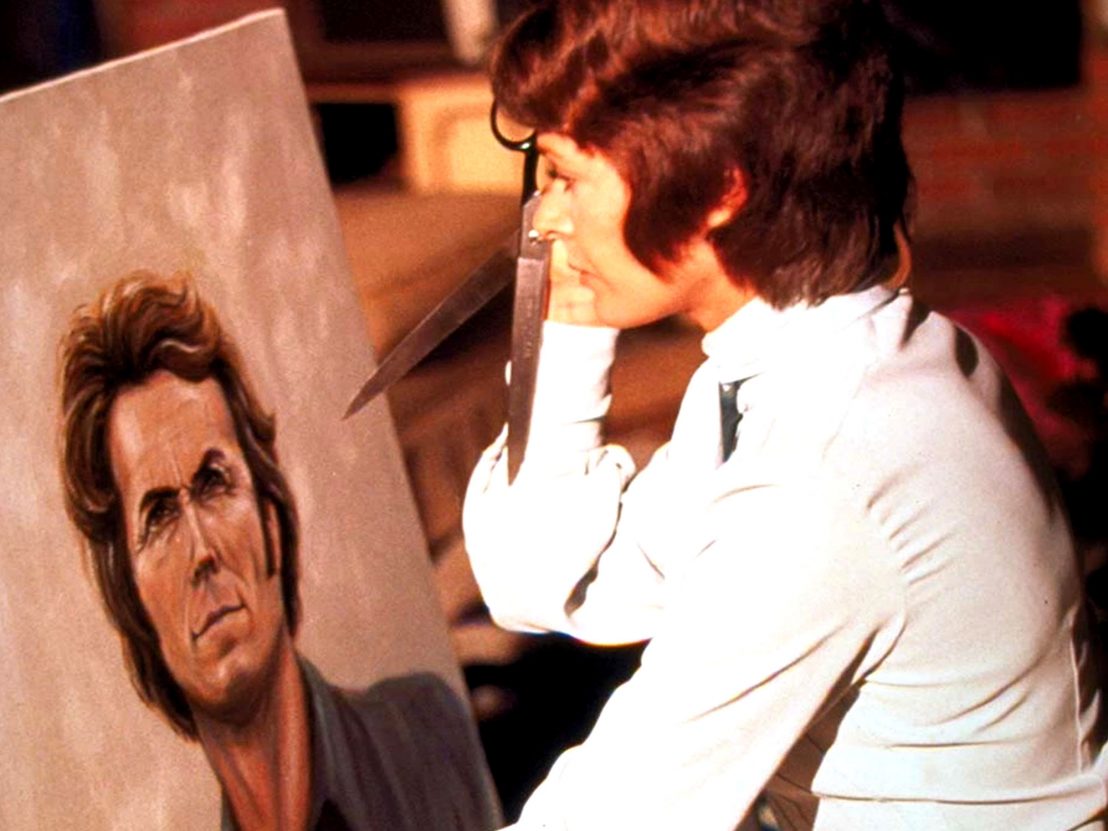

It’s strange to consider now, but in the early 1970s American film studios were uncertain about the directing abilities of Clint Eastwood. Despite being such a prominent screen figure, Eastwood’s urge to get behind the camera was initially met with scepticism. Having cut his teeth learning from the directors he worked with, in particular Sergio Leone and Don Siegel, Eastwood was soon in a position to make that switch. On the evidence of his directorial debut, Play Misty for Me, critics and studio bosses needn’t have feared.

The film follows Eastwood’s freewheeling, womanising Californian DJ, Dave, who lives in the idyllic coastal town of Carmel-by-the-Sea and hosts the late-night blues and jazz shows for the local radio station. He takes callers’ requests and doesn’t notice that a regular listener always requests Errol Garner’s ‘Misty’. After his latest session, he pops into a bar where he believes he picks up Evelyn (Jessica Walter). In reality, Evelyn is the fan that rings every night to request the song; her obsession with Dave is already out of control.

Dave’s rekindling of his previous relationship with Tobie (Donna Mills) causes Evelyn to become increasingly manic in her attempts to possess the DJ. She stalks him, crashes interviews and work meetings, and even attempts suicide when it’s clear that she is unwelcome in Dave’s house. Just how far is Evelyn prepared to go in order to have Dave to herself?

Eastwood’s debut is a dark film. He harnesses some of the same paranoia seen in Siegel’s films (the director himself making a cameo as a bartender). Yet, for its period, Play Misty for Me is also refreshing in its approach to obsessive tendencies, celebrity infatuation, and even its concern over the removal of barriers in the name of Free Love. With all of these aspects, the film hides many writhing counter-culture horrors underneath its hazy Californian paradise.

Aside from its obvious visual qualities, there is also an unnerving authenticity to the film’s drama. This is especially true of Evelyn’s toxic tactics in getting Dave to seemingly commit to things he repeatedly suggests he doesn’t want. This authenticity stemmed from several real-life incidents. The character of Evelyn was inspired first by an anonymous DJ based in Mendocino County, who was stalked intensely by a fan, and an incident from Eastwood’s life when he was still finding his feet as an actor in the 1950s.

When Eastwood was 19, he met a 23-year-old woman who became infatuated with him. As he told one biographer, “There was a little misinterpretation about how serious the whole thing was.” This plays out note-for-note in Play Misty for Me’s early scenes, a misunderstanding quickly descending into something more uncomfortable. Much of the power of these – at times unbearably awkward – scenes comes from the superb Jessica Walter, who possesses a wild-eyed mania that puts her on a par with several of the era’s most unnerving screen villains.

Eastwood had further issues with the studio, who were unsure why the villain of the film should be a woman. “The studio people said, ‘Why do you want to do a movie where the woman has the best part?’” Eastwood recalled to another biographer. “My reaction was: ‘Why not?’ I figured, ‘Why should men have all the fun playing disturbed characters?’”

Walter relishes every moment on screen, her sickly positivity utterly chilling. A one-night stand quickly leads to Evelyn effectively moving in, sneakily having a key cut for the front door and generally veiling her manipulative nature behind pleasantries. It’s a believable scenario in which simple acts of kindness are weaponised, escalating until Evelyn resorts to the most extreme act of self-harm; a flash of violence hinting at even greater horrors to come.

The era of Play Misty for Me was a comedown. The accelerated years of the 1960s had restructured, questioned and destabilised just about every aspect of Western society, from its relationship to drugs to its received political norms. The clichéd vision is a mix of social and political revolutions, psychedelia and the popularised counter-culture. “We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave…” as Hunter S Thompson wrote in ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’, looking back after the wave had crashed.

As when Thompson was writing, the wave was violently receding by the time of Play Misty for Me’s production. Its residue remained, characterised by a different collection of clichés: Altamont, Charles Mansion, serial killers and drug causalities. The changes also brought about by the era’s sexual revolution and Free Love finally realised in full a proudly permissive society in the midst of these nihilistic elements.

The film’s refreshing tone comes as much from questioning the carefree, fun-loving image of the ’60s, reinstating a sense of consequence. The world that emerged from this period of apparent revolution was one of greater sexual education and access to contraception, but it was still ultimately drenched in misogyny. Free Love was a double-edged sword when unleashed within such an intensive period of patriarchy. New freedoms became abused, the system still rigged.

“Evelyn could easily have been another Manson Family member, had she dropped more acid.”

Eastwood’s gift in the film is to invert an already unacknowledged set of issues surrounding these collapsing social barriers and use celebrity culture to enable a switch in gender. While many films position the stalker-stalked relationship as being instigated by the man, the post-Beatlemania, new-celebrity world of the ’70s allows characters like Evelyn to feel more believable. It’s the same world that formed Manson Family members like Linda Kasabian, Susan Atkins and Patricia Krenwinkel; Evelyn could easily have been another Family member had she dropped more acid.

Though based on events that happened well before such social shifts occurred, it’s difficult to see them happening in the same way as in the early ’70s. As such, it’s useful to compare Play Misty for Me to Vincente Minnelli’s The Sandpiper – not only do both films use the same locations (their opening title sequences are remarkably similar) but they also chart an amorous falling out. Only a few years separate the films and yet the societies they portray could be decades apart. The world of The Sandpiper is equally complicated but not necessarily one that would lead to the sort of demented, shocking finale of Play Misty.

When looking at Las Vegas in the early ’70s, Hunter S Thompson wrote “…with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark – that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.” He was referring to the revolutionary flare of the late ’60s and its inevitable burnout. Perhaps that same high-water mark hit the misty coasts of Big Sur, right along the cliffs of Carmel-by-the-Sea where the naivety and optimism of the age hit the same rocks as Evelyn’s body in her last fateful effort to violently grasp the new freedoms of the age with both hands.

Published 12 Aug 2021

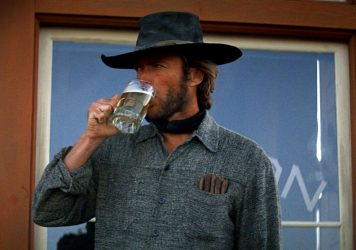

This controversial 1973 western ranks among the director’s finest works.

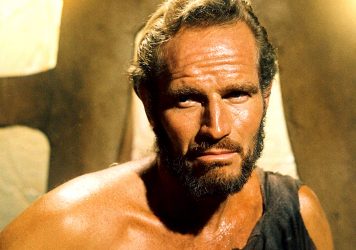

Franklin J Schaffner’s satire was a response to an era of social upheaval.

Don Siegel’s period thriller shows this icon of screen masculinity at his most pathetic and vulnerable.