Arguably the quintessential Hollywood poster boy for stoic masculinity, Clint Eastwood’s most iconic characters have always embodied a potent form of lone wolf heroism, filling the shoes of a rugged host of maverick cops and solitary gunslingers unafraid to operate outside of society’s rules in order to bring the corrupt and the wicked to justice. Though their methods may often be morally questionable and their motivations at times suspect, we put our trust in these authoritative figures because we assume that the ends will justify the means and, perhaps more importantly, because Clint looks really fucking cool when he’s shooting people.

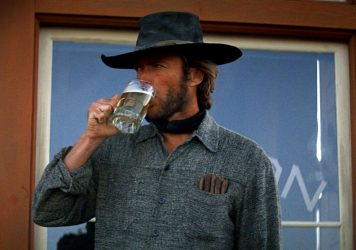

Enter Don Siegel’s The Beguiled, a 1971 adaptation of Thomas P Cullinan’s 1966 Southern Gothic novel that subjects a pre-Dirty Harry Eastwood to the most brutally emasculating, tragically undignified character arc of the legendary actor’s career. Here there is no ambiguity about the moral shortcomings of Eastwood’s character, the sleazy and manipulative Corporal John “McBee” McBurney, as this psychosexual wartime drama mercilessly strips away the tough and endearing persona of its lead to reveal a thoughtlessly impulsive and feeble man beneath.

The first sign that we are in for a somewhat queasier affair than your average Eastwood thriller comes in the opening minutes of the film, when half-dead Yankee soldier McBee locks lips with 12-year-old Amy (Pamelyn Ferdin) as they hide from nearby Confederate troops. She subsequently guides McBee back to the Miss Martha Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies, a charming refuge from the horrors of war where blossoming women are taught to be ladylike and proper. The fact that Miss Martha herself (Geraldine Page) conceals an incestuous past with her deceased brother is as an early indication of the repression and unease that saturates this environment through all the prayer sessions and courses in etiquette.

Though the school staff’s initial plan is to nurse McBee back to health before handing him over to the Confederates, the soldier’s seductive but insincere charm quickly promotes him from a prisoner to a cherished helper who becomes romantically involved with several of the multi-generational residents of the institute. Up to this point, Eastwood was best known as the Man with No Name, a character originally conceived for Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy, with the very title suggesting a mystery and solitude that framed Eastwood as a figure to be sexualised and romanticised – but only from a distance. The Beguiled can be considered anomalous in Eastwood’s career simply for placing him in such an explicitly erotic context.

Nonetheless, the sexual power plays of Siegel’s film are just the primary manifestation of its richer deconstruction of masculinity. As one of the few school residents that McBee fails to seduce, house slave Hallie (Mae Mercer) makes the piercing observation that the soldier is a slave in his own way. “I’m nobody’s slave,” McBee defiantly responds, to which Hallie retorts, “You mean you just went out and got yourself shot up because you like being shot up?” In this and other moments like it, Siegel undermines wartime machismo to suggest that the recklessly confident McBee ultimately has little command over his own fate.

This is especially evident once McBee’s luck runs out and the revelation of his secret trysts with three different women at the school is met with a violent and jealous response. After being beaten with a candlestick and pushed down the stairs, his figurative castration is finalised with the amputation of his leg – a medical procedure that we suspect in part to be a gruesome form of revenge from the unstable Martha Farnsworth. McBee stumbles through the film’s final stretch as a pitiful figure nursing an impotent grudge. Harry Callahan would typically be busy dispatching the last remaining street punks by this point, but McBee instead erupts into a drunken rage that accomplishes little more than accidentally killing Amy’s pet turtle, making yet another surprisingly dangerous foe out of the schoolgirl.

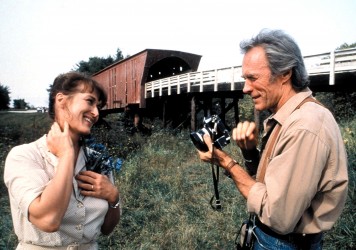

Though Siegel’s adaptation is not without its problems (its simplistic depiction of female sexuality certainly leaves some fertile ground for Sofia Coppola to explore), it endures as both an entertaining period thriller and an important chapter in the wider Eastwood canon. The Beguiled was not the last film to explore the dubious implications and underlying psychology of the actor’s public persona. Indeed, Eastwood himself has mined this theme with acute self-awareness in numerous directorial ventures – though none so wildly uninhibited in the moral comeuppance unleashed upon this renowned screen badass as Siegel’s twisted cautionary tale.

Published 24 May 2017

This controversial 1973 western ranks among the director’s finest works.

A comprehensive rundown of veteran screen icon’s formidable work behind the lens.

Sofia Coppola stuns the Cannes crowd with an intoxicating film about repressed female sexuality.