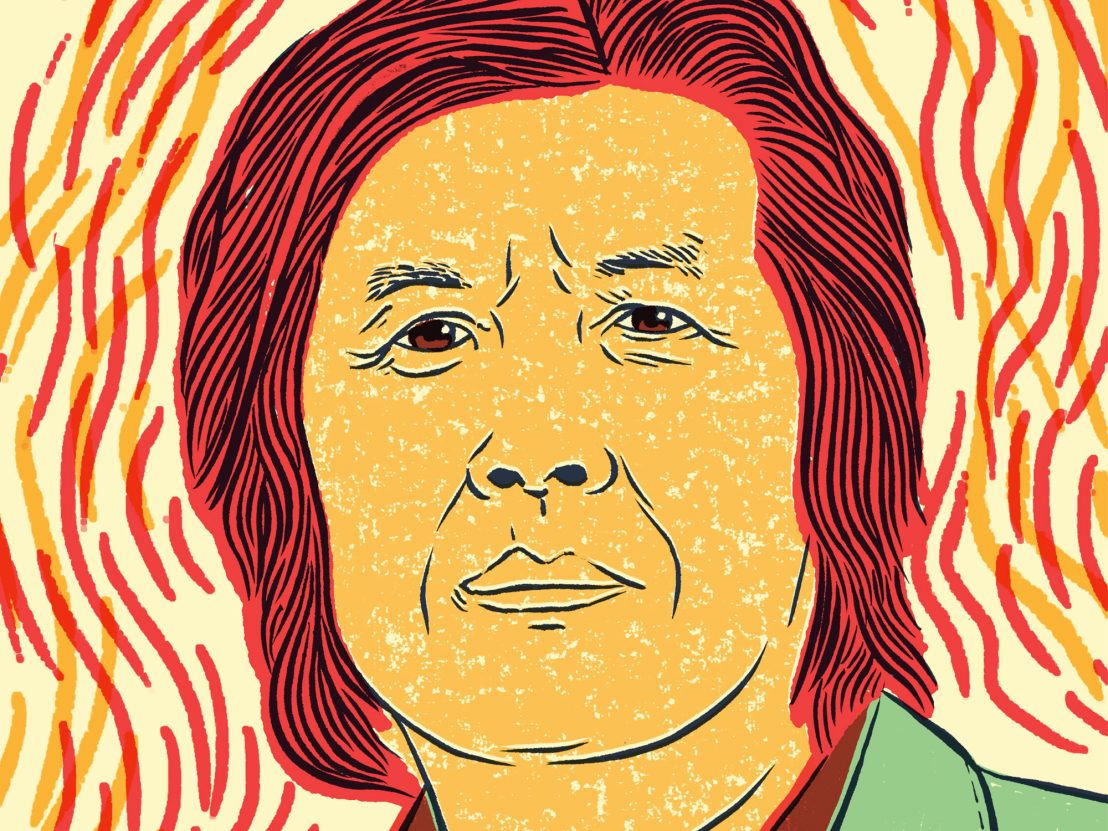

The South Korean maestro talks literary inspiration and his mysterious new psychodrama, Burning.

A new film by the South Korea’s Lee Chang-dong is an event. He only makes bangers, and it’s been eight long years since he graced us with the magisterial Poetry. LWLies met the writer/director on the occasion of his triumphant return with Burning, a strange and intense three-hander encompassing romantic and class-driven jealousy, adapted from a short story by Haruki Murakami which was originally published in the New Yorker.

LWLies: The Murakami story is very spare. Was there ever any consideration towards finding a cinematic style that matched that of Murakami’s prose?

Lee: When you read the Murakami, it’s quite slight in terms of its mysteries. It’s only about why the barns were burnt, and why the girl went missing. I was really drawn in by the fact that we didn’t know the ending. Usually with mystery stories, everything is revealed at the end, but this one was different. So I wanted to explore its small mysteries, expanding them into big ones. That was the main direction I was heading.

Murakami took on Faulkner, a completely different stylist, as inspiration for his story. Do you think the cinematic language, or even perspective, of Burning shows any specific affinity to one over the other?

It’s a very good question. Of course, Murakami and Faulkner are completely different, they’re at different ends of the spectrum. But it’s not a question of style, it’s about a gaze, about a way of living. These are two different authors with different ways of looking, different ways of living. Today we are living in Murakami’s world; not in terms of a literary world, but the actual one we’re living in. Murakami is a postmodernist, and we’re living in a postmodern world. Faulkner’s world was very different, but you could describe Burning as a Faulkner story set in Murakami’s world.

How does your world, or gaze, separate or converge with those of Faulkner and Murakami?

I’m closest to Faulkner. My attitude towards life, towards seeing the world, is closest to Faulkner’s, but I’m living in Murakami’s world, which is a limitation. I’m seeing the world as Faulkner sees it, but nowadays audiences don’t want to see things that way because they’re closer to the Murakami experience. The world is changing rapidly, and nobody wants to be serious. Questioning something isn’t seen as being cool.

Jong-su is actually reading Faulkner in the film. Given what you just said about affinities in worldview, does that mean you feel closer to his perspective on the film’s events? Was that different to your writing partner, Jung-mi Oh?

Faulkner’s literature always speaks of hardship, and when he won the Nobel Prize, he spoke of wanting to represent people who endured this hardship. That’s his attitude. I think literature can help people who are suffering, it can rescue them. Readers’ taste is changing, and the world is changing, because people don’t like being serious, they prefer Murakami’s lightness of existence. Jong-su sees the world like Faulkner, but my life, as far as others might see it on the surface, appears closer to Ben’s. Lots of young audiences in Korea can’t relate to Jong-su, because they’re living in Ben’s world too. Jung-mi was closer to Hae-mi; her femininity, her questioning the meaning of life, her freedom.

When you’re writing a narrative or metaphorical mystery like Burning, do you have your own set of answers to the film’s questions? Were they different to those of your co-writer?

I don’t have any answers. Burning is only superficially a mystery-thriller, the mystery elements lead us into the mysteries of our lives, our politics, our economy and sociology. It also makes us question what we see and what we don’t see, what exists and doesn’t exist. It asks what is metaphor, what is storytelling? What is film, what is even filmmaking? I don’t have any answers for these questions, and I’m not hiding anything, but I do need to share the concept of what’s immediately there with the crew and actors. With actors, though, you can’t carry on like this, because they’re bringing something from inside themselves. For example, with Steven [Yeun], I gave him the responsibility of who Ben is. So he might have had some answers of his own, in order to deliver him, but I didn’t.

What were the specific qualities you were looking for in each of the actors when it came to casting?

Ah-in Yoo, who played Jong-su, is very big and famous in Korea. He’s well known for delivering strong characters on screen. In contrast to that, Jong-su is a very passive character, who’s not good at showing his emotions, so I thought it would be good to have an actor who could keep everything inside before blowing up at the end. I thought it would be very interesting to see that transition from his previous work. With Hae-mi, the actress had no experience in films, no shoot experience whatsoever. I picked her out from an audition, thinking she had this pure quality, but also a double side to her personality that I thought I could use.

What do you mean by double side?

She came across like a pure school girl, almost like a blank canvas, but I was wondering, “Is that all she’s got? It looks like there’s something underneath.”

Murakami is a lot more damning of the character, as far as she relates to men. Did you want to soften that more unforgiving quality when it came to Hae-mi?

Hae-mi disappears in the middle of the film. This kind of story has been around for many years, but it’s always about finding the woman. My story is about the woman who is missing. I didn’t want to repeat the old story type, I wanted to find who she really is, which is the core of the film as well. We don’t know whether she’s lying to people or not. She leaves suffering as she dances, while she’s looking for the meaning of life. Others might think she’s useless, but in looking for the meaning of life, maybe she’s the only one who’s serious about it. Who Hae-mi is is the core of the film, and the core question of the film.

Burning is released 1 February. Read the LWLies Recommends review.

Published 1 Feb 2019

Lee Chang-dong’s sly take on a Haruki Murakami short story is a slow-burn mystery touched by genius.

To celebrate the release of Burning, we survey the South Korean writer/director’s earlier work.

The South Korean genre whiz behind Snowpiercer and The Host discusses his latest creature satire.