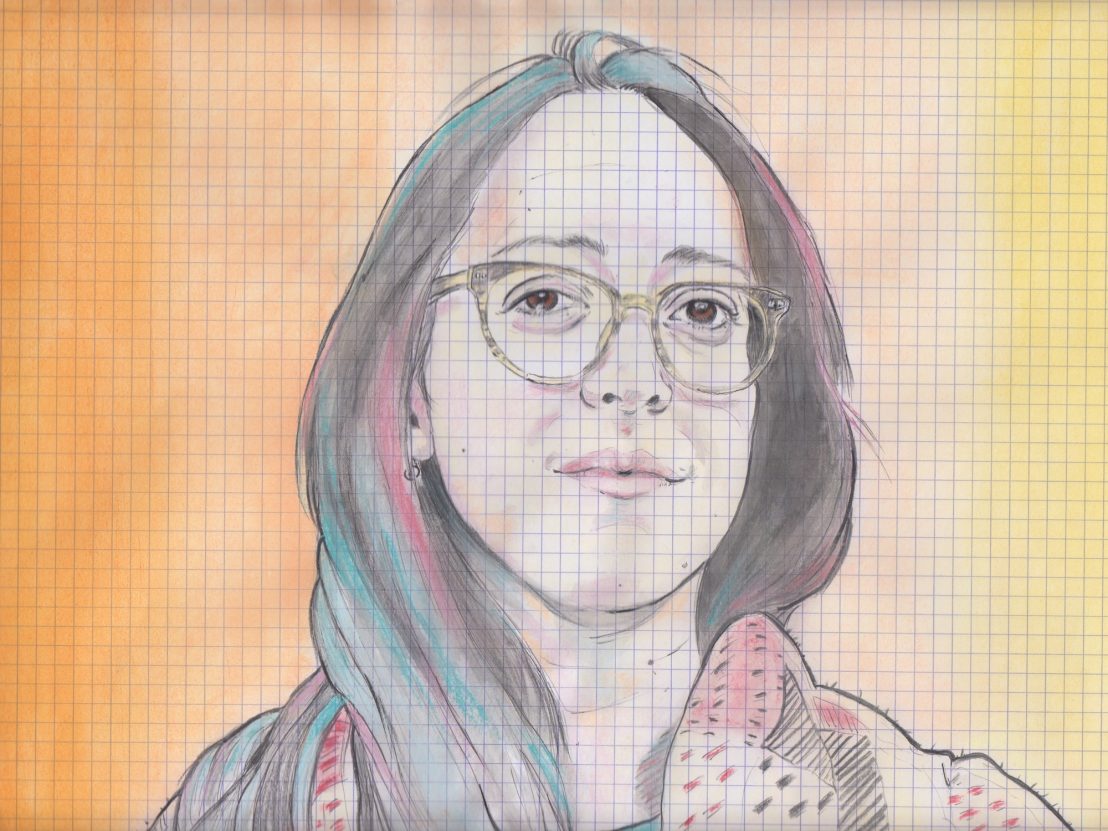

The director of the excellent Too Late to Die Young talks about recreating a rural commune from her childhood.

Dominga Sotomayor’s impressive third feature, Too Late To Die Young, sees her returning home, from Argentina to Chile. Travelling back in time to the end of the 1980s, the film presents a cross-section of a non-traditional community, following a small cluster of families attempting to live self sufficiently outside of Santiago’s city limits. She talks here about the role of the film’s location, a commune constructed specifically for the film, and what it means to her and to the characters in the film.

I wanted to ask first about the location of the film. Where is it firstly, and what does that place means to you, if anything?

For me, the location is the main character. The most personal thing about the film is this place. I grew up in a community that is similar, so there are elements of the place I grew up in. When democracy arrived to Chile in 1989, my parents decided to move to a commune that was still being constructed. We were living with about ten other families, without electricity or phones. It was very special. Twenty years later I was living there by myself and I realised how much had changed. It couldn’t be as it was in my childhood. There were around 400 houses, it was full of people.

So it became more like a real city?

Yeah, more modern. I wanted to make a film where the time and the space was very clear. I built this new community to be similar but not the same, a space where the limits are not clear.

So it’s not a real commune where people live?

Now, yeah it’s a real community. We built something to resemble a commune as it would have looked in the beginning, in the ’90s. December 1989, Pinochet was kicked out, the dictatorship ended. That particular summer was when my parents decided to move to this place. In March, the first democratic president started, and until December there was nothing. It was a transitional period, which formed the inspiration for the film.

Did your parents move then because they had the freedom to do so, or because they were opting out of the new society, or neither of those things?

It was just when democracy arrived that they decided to move, but we never thought of in that way then. Now, with time, it feels obvious that it was an exile. The city was very grey and there were looking for a place that they could build for themselves. My mother is an actress, and those around her were all involved in culture, which there was no space for in the city. What was interesting for me was that it was outside of definitions. It’s not like a community with its own clear ideologies and rules. You cannot really describe or define it, it was just a possibility for a different life, to be close to nature and freer. The starting point had to do with these permeable limits between exterior and interior, between nature and humanity, and between femininity and masculinity. It was playing with these digressions

So you started with the location, and built the characters and the stories around the place?

Actually, I started with the fire. There was a real forest fire when I was little, when I was five year old. I never saw the fire because I was in a water tank, thinking I would be safe there. It was a big thing for a child to experience, there was lots of screams and commotion. Then 25 years later I found these VHS tapes that our neighbour had recorded of the fire. I saw the fire for the first time. When I saw it, it was the starting point of my film. I could imagine the burning, the smoke rising in this remote place, but what most attracted me was the idea of a group of women and children trying to fight against the fire with trees, which is in the film. it was so absurd that these people tried to retreat from the city, only to be met with nature. It’s about going back to nature, but nature is what ultimately causes them damage.

It’s the illusion of a new world, but in reality they are reproducing the same things, as humans tend to do.

There’s all sorts of things behind the film then: the dictatorship; the new democracy. But they are not directly in the film – they aren’t mentioned. They may be in the texture of the film, or briefly mentioned in conversation, but it’s background.

Was this always the intention, to not have these things as plot points, but something in the air?

Yeah, I wanted to capture the spirit of this transition. I wanted to look at its emotional impact on the characters, rather through something concrete. I think the film is timeless also. My inspiration is the ’90s, and this one specific summer, but really it could be any other summer. This is a political position. We thought democracy would be the solution, but found out it was just another circle. There’s a continual hope for a new beginning.

The film is circular too. It could be an installation. The dog is the start and the end.

Yeah, it’s like a circle for me. It was important that one layer would be about these teenagers who love too early, who experience illusions, but the other layer is the adolescence of the country, with all this pain and this desire to restart. Also New Year’s Eve has this feeling – it’s like a reset. I like what is in-between. I like working with scenes that don’t add up. In these moments – these intersections between important things – you can dip into emotions. I wanted emotions, not big events.

How did you cast the film, and once you knew who would be in the film, how did you work out their relationship to one another?

It was like a big tree, with lots of points connecting people. It’s a film about non-correspondence as well: everybody wants something they don’t have. So it was messy, but it was also clear. We had to work out the relations first. For the casting, it was challenging as I decided to work with non-professional kids. We made a call for kids currently living in a commune. We chose 10 kids and 10 teenagers, made a workshop where we make music and play games. From this, we selected the main characters, then got the remaining kids to play the others. We didn’t want to reject anyone. Theres also professional actors, adults without any experience, Sofia included. It was a random and eclectic casting. I didn’t rehearse much, but I tried to bring them into the same world.

And how did you work with the actor who plays Sofia (Demian Hernández)? Did the two of you work out the character together, and how did that character become the one who is the closest thing to a protagonist in the film?

It was always like this. I think at the editing, Sofia became clearer. I wanted Sofia, Clara and Lucas to be equal, but Sofia’s character became more prominent in the end. Damian was a friend of a girlfriend of my brother, so very close, and had never acted before. I don’t think you can create complexity, you can just portray complexity. When I met her (Damian is now transitioning), I had this feeling she had lived more that most people her age.

As a person you mean?

Yeah, I saw things were happening there. I could sense some turmoil. I didn’t give them a script, we were working scene by scene, very personally. It was a really personal relationship and I worked with them in a very close way. It’s interesting because after making the film Damian was going to be transitioning, which was something I didn’t know about before.

It wasn’t something happening during the filming?

It wasn’t during the film. It’s not a theme of the film either, but it makes a lot of sense, because the film contains a lot of transitions, and you can see that something very strong is happening to her.

Was it shot some years ago then?

No, last year (2017), in March and April. He said that through the way we worked on the camera, he was connecting with his own sense of turmoil, and going through the film helped him to understand what was going on.

It was another workshop in a way?

Yes, Damian told me before Locarno, ‘This film is the last portrait of me as a girl. But I will premiere it as a boy.’ We’ve been together for the whole process, and the premieres.

Just out of interest, then, has this become more of a conversation than the film? Does it get asked about it a lot?

People do ask a lot, and I have doubts. I’d prefer people don’t know about it in advance, because it might create some expectation about the film. In Chile, It’s delicate. His grandmother doesn’t know.

I was thinking about memory a lot, it’s your memories, but the characters seem conscious of the process of memory making. How does memory work for you in relation to film?

I have a very bad memory. I wanted to capture things I am forgetting. I think the film plays with memory on many levels, its a memory of a period of time in the country. It’s the emotional memory of what was happening with the people at the time. It’s also a capture of time for me, but one that is blurry, and for the characters, all of them are going from one place to another, where they need to learn how to lose something.

I think the structure of the film works like memory too, jumping from one significant thing to another, and sometimes staying on things are insignificant too, but remain in the memory. All together something is built. Memory is a fiction, you don’t really remember things as they are. This is a film about the past, but it is remembered from the present. It’s a memory in present time.

Read our review of Too Late to Die Young here.

Published 24 May 2019

Kids hang loose as their parents attempt to build them a new civilisation in this easygoing political fable.

By Matt Thrift

It took the best part of a decade to bring Zama to the big screen. Its writer/director tells us about her epic journey.

A smorgasbord of international cinematic treasures was on offer at this year's festival.