James Gray returns with a deceptively traditional and wondrously transportive cinematic odyssey.

James Gray’s ambitious latest, The Lost City of Z, is an intoxicating, sweeping colossus that honours every quality of movement, vision, and dynamism inherent in that dated term “motion picture.” Adapted from David Grann’s 2009 chronicle of the life and adventures of early 20th century British explorer Percival Fawcett, Gray’s long-gestating passion project transfers its subject’s exploits to the big screen and imbues them with some of the purest and most affecting movie-movie thrills within the writer/director’s entire body of work.

When we first meet Percy (Charlie Hunnam), he is a strapping British ranger and skilled cartographer with a contented home life but with no medals to offset his tarnished family name, thanks in large part to the conduct of his deceased father, a disgraced drunkard and gambler. Gunning for battle and redemption, Percy is disappointed when the Royal Geographical Society enlists him to remap land in Bolivia (“land of the primitives,” as one higher-up passively describes it) in order to stop a territorial war between Bolivia and Brazil, a treacherous assignment that will take years and draw him away from his young son and pregnant wife (Sienna Miller).

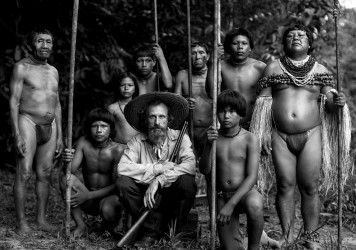

Accompanied by a ragtag outfit, including an aide-de-camp played by a wily, scraggly-bearded Robert Pattinson, Percy plunges into his 1906 mapmaking mission through the Amazonia region, only to find his attention distracted by a South American slave called “Willis” (Johann Myers), who descriptively murmurs about an ancient lost city of gold. After a perilous journey of infighting, diminished rations, and attacks from indigenous tribesfolk, Percy and his crew find themselves in uncharted territory, filled with sophisticated pottery and faces carved onto trees. Percy takes these findings as auspicious signs that the now-disappeared Willis was telling the truth about this hidden civilisation, which he names Zed. He returns home as “England’s bravest explorer” but is unable to shake his obsession. Years later, he sets sail to find his lost city once and for all.

It isn’t hard to imagine any number of filmmakers tackling Fawcett’s mythic legacy – Werner Herzog, Terrence Malick and even Steven Spielberg all spring to mind as directors who could fulfil both the vast visual scope and fabled romanticism of Fawcett’s thrill-seeking expeditions. Even though Gray appears incapable of making the same film twice, there isn’t anything in his filmography which suggests him as an obvious contender for such a mammoth undertaking.

With The Lost City of Z, Gray announces himself as one of world cinema’s most gifted classicists, a distinction evident from the film’s very first moments, in which he subtly disrupts our expectations during scenes that will resonate with anyone who is even remotely familiar with Masterpiece Theatre. A woman buckles and struggles from beneath her corset. An alcoholic substance skids across a grimy sink in the same direction as the locomotive our protagonist embarks on in the following shot. The film opens with a thrilling breakneck hunt among British infantry in Ireland, during which men and horses collapse and trample over one another, a sequence of great beauty and violence.

Gray is aided by the astonishing work of cinematographer Darius Khondji, who draws on the deeply-textured, golden-hued aesthetic of The Immigrant on an equally rich but far more expansive scale. Speaking of The Immigrant, there is no single performance here to rival Marion Cotillard’s harrowing, silent era-evoking tour de force in Gray’s 2013 film. But all involved do a fine job of slotting into the period while still managing to stand out, particularly Hunnam who gives a dashing lead turn that makes the case for his repeatedly-deferred movie stardom. Elsewhere Angus MacFadyen has a ball as high-ranking explorer James Murray, who accompanies Fawcett on his second expedition before jeopardising the entire mission with his insolence and unfitness. Sienna Miller is very good too in a role characterised not simply a supportive unit but as a self-styled independent woman who is barred from participating in the adventure both by society and her own husband.

That Gray hands the film’s entire ending to her, culminating in a final shot of breath-catching and tear-stifling invention, is at once a boldly emotional gesture and yet another indicator of Gray’s rare filmmaking instinct. The Lost City of Z may be his most overtly conventional work to date, but there is nothing common about the sheer scale of his ambition. Like his own restless hero, Gray is unafraid to wander deeper and deeper into the jungles of his own imagination, an undaunted explorer who can see the wonders that consume him and longs to show them so as to understand why.

Published 17 Oct 2016

Hopes were sky high for James Gray’s lavish NY period drama, but this one left us cold.

Ciro Guerra’s film is a stark reminder of the destructive nature of European colonialism.

A jaw-dropping spectacle and brain-melting existential nightmare, Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam opus is touched by genius.