Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent – a pictorial, sensuous, tinglingly tactile movie – is as valuable and revelatory for what it doesn’t show as for what it does. The film operates on a metaphysical level alongside its rich physical representations, so that intangible things like memory, spirituality, dreams and collective culture feel as alive as the film’s flesh-and-blood characters. And in offering up this level of interpretation, it admonishes Western culture for its greed, materialism and narrow-mindedness.

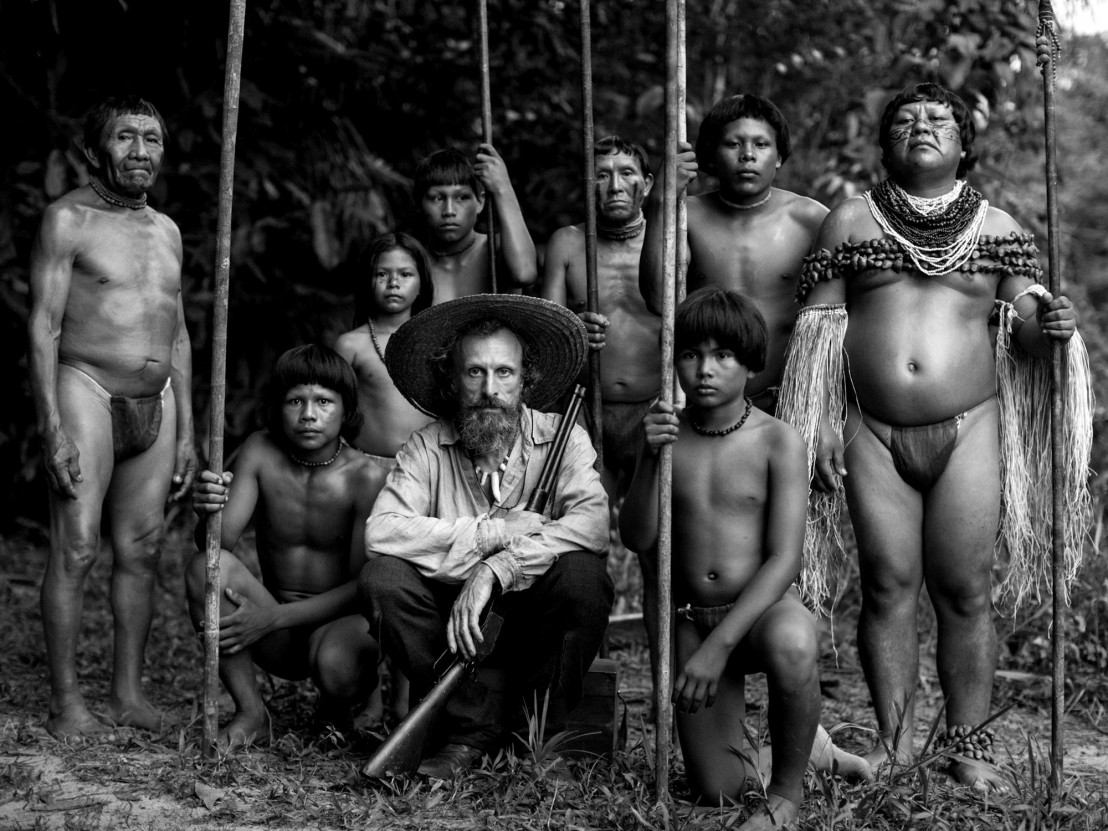

At the film’s outset, we see how an Amazonian shaman, Karamakate, in his early years and as an old man, is engaged to guide Theo and Evan, two Western explorers, down the river in search of the legendary, sacred yakruna plant. Told across two different timelines, the film weaves connections between its stories based on time: Karamakate’s anger, regrets and sorrow loom over the latter narrative, colouring its events. Meanwhile, Guerra uses perspective to allude to the incompatibility of Western culture and ethnic Amazonian tribespeople.

When we see the white explorers arrive, the camera is planted firmly with Karamakate: the outsiders, the intruders, are the white men. This perspective is in opposition to other exploration works, like Joseph Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ or Werner Herzog’s ‘Fitzcarraldo’, in which natives are presented as other and unknowable. The film also ends with Karamakate, showing the depth of his loss and the extent of his solitude – its focus on time and perspective converging to suggest all of the ways in which his culture has died out over the years.

Embrace of the Serpent also uses metaphor and imagery to conjure intangible concepts. The title may allude to the suffocating, venomous clutch of Western culture, constricting the life out of the indigenous cultures it purports to have “discovered” – but the eponymous serpent might just as well stand for the Amazon, snaking its way through the dense rainforest giving life to everything it touches. Karamakate, as an old man, asks Evan how many sides the river has: the white man answers that it has two sides, much to the shaman’s scorn. It’s clear through this exchange that white Western culture is seen as rigidly, fatally attached to physicality and empiricism; it simply cannot comprehend the mysticism of other cultures.

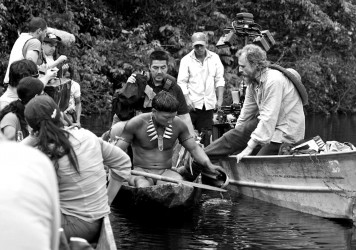

Both explorers are married to their physical objects: a gun, a compass, a photograph; items that make no sense in the old world in which they find themselves. So obsessed are they with material possessions that they are hindered in their mission – literally weighed down in their boat. The young Karamakate laughs at Theo because he does not understand the river as he paddles his canoe, splashing about like an idiot, hopelessly out of sync with its currents, beats and motions. In turn, the film uses the river as a visual metaphor for time, its ebb and flow feeding the rhythms of the different timelines, showing how nature is constant but civilisations are perishable.

The film also offers up a dichotomy of spirituality and religion, opposing the fake and egomaniacal rituals of Western religion to the more harmonious spirituality of Karamakate, which draws on his surroundings. From the yakruna – a tree living off the same earth and water as him – he draws a psychotropic essence that allows him to step outside his own world. Western religion, in the damning representations the film makes of it, operates the other way around: from the outside in, with twisted preachers and missionaries harnessing false power in order to foster a cult in their own image.

Only when you engage with the film on a metaphysical level – through its allusions to the death of culture, to the spiritual and even the supernatural, to Karamakate’s unseen life – does its sheer physicality hit you. Only then does it smack you in the face: we are only able to learn about these fading cultures because of the painstaking physical recording of them by the very people who destroyed them. While Karamakate is able to live in his world – to exist in the moment – it is the cartographers and plunderers of this world who are best positioned to depict it, even though they can never fully understand it. The film’s absolute understanding of its environment, the way it records the gentle wash of the river on a bank, the greasy slurp of a frog, the stark white body of a single standing tree, is something that can no longer be remembered or grasped.

Published 10 Jun 2016

By Matt Thrift

Ciro Guerra’s psychedelic Amazonian odyssey is one of year’s most potent and strikingly original films.

With his spectacular new three-part film, Arabian Nights, director Miguel Gomes proves himself to be a grand master of combining music and image.

Embrace of the Serpent director Ciro Guerra on the logistical and spiritual challenge of shooting in a rainforest.