Ken Loach and Paul Laverty return to Cannes with another bitter requiem for the working class.

Something is rotten in the north-east of England. A full decade on from the Great Recession, ordinary working-class folk like Ricky Turner (Kris Hitchen) are still feeling the pinch thanks to austerity measures enforced by successive Tory Prime Ministers. The protagonist of Ken Loach’s latest scathingly bleak survey of modern Britain is a down-on-his-luck grafter who, like so many people stuck on zero-hours contracts, is finding it hard to make ends meet.

While Ricky’s wife Abby (Debbie Honeywood) enjoys her work as a carer, he’s running out of options as a workaday handyman. But Ricky has a plan. After persuading Abby to sell her car to pay for the deposit on a new van, he signs up to be a franchisee with a local delivery firm. For the first time in his working life Ricky appears to be in the driving seat of his own destiny. He powers around the city’s tower blocks and trading estates, dropping off parcels to mostly satisfied customers – the only incident of note being a petty squabble with a dyed-in-the-wool Geordie who can’t resist having a pop at Ricky for supporting Manchester Utd.

But it’s not long before the wheels start to wobble. Ricky’s teenage son, Seb (Rhys Stone), has started skipping school and playing up at home, and younger daughter Liza Jane (Katie Proctor) is beginning to bear some of the emotional strain brought on by the family’s increasingly desperate situation. As tensions run high at home, motorless Abby struggles to make her regular appointments while Ricky clashes with his boss, Maloney (Ross Brewster), the self-proclaimed Patron Saint of Bastards who in the film’s standout scene delivers a callous, obviously rehearsed speech that’s like David Brent on steroids.

Filmed on location in and around Newcastle upon Tyne, Sorry We Missed You sees Loach pick up pretty much where he left off two years ago with I, Daniel Blake, which saw the veteran director scoop his second Palme d’Or two (this is his fourteenth nomination overall): railing against the current government and faceless corporations which have conspired to widen the gap between the rich and the poor. It’s a pessimistic, some might say deeply cynical film, though the script by Loach’s longtime collaborator Paul Laverty does offer a few faint glimmers of hope.

For the most part, however, Laverty approaches this delicate subject with sledgehammer subtlety. At the time of writing, the spectre of Brexit still looms large over the British public, and it looks more than likely that we will have a general election within the next six months. As such, a film about a deepening national crisis should feel urgent and shockingly relevant; it should galvanise its audience into action or, at the very least, give them food for thought before they next enter a polling station. But its focus is too shallow, its mode of storytelling too blunt-edged and soapy, to have the desired impact.

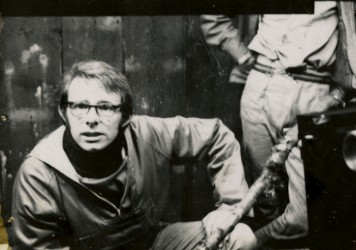

Regardless of whether or not you share his socialist agenda, it’s easy to see why Loach remains such a staunch champion of the working class: he came of age as a filmmaker in the late 1960s, a time of massive social, cultural and political upheaval, yet it could be argued that the people he has put on screen throughout his career have never had it so bad. The problem, then, lies not with Loach’s message but the hackneyed manner of its delivery. British film may not be as radical and politicised as it once was, but it needs a new voice. Loach lit the fire, now it’s time for someone else to pick up the torch.

Published 17 May 2019

This 1966 TV play on a young woman’s descent into homelessness has lost none of its impact.

Ken Loach’s latest polemic has a vital message that’s diluted by some heavy-handed direction.

One of Britain’s most lauded and long-serving leftwing voices gets the whistlestop biog treatment.