Button-pushing auteur João Pedro Rodrigues returns with a work of tantalising, twisty spirituality.

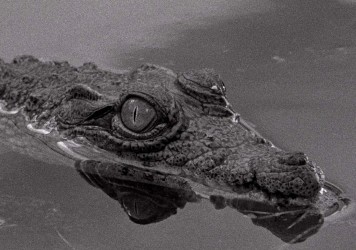

Things are certainly stranger by the lake in João Pedro Rodrigues’ The Ornithologist, in which the provocative Portuguese writer/director spins a compelling queer fable from the shipwrecked story of Saint Anthony of Padua, emerging with a sublime and hallucinatory puzzler that, from scene to scene and even second to second, is entirely impossible to predict.

The film may open with a solemnly-placed homily quote, but that’s as conventional as it ever intends to be. Rodrigues quickly dodges any inclination towards faithful hagiography and instead reimagines Saint Anthony’s tricky voyage into that of Fernando, a contemporary and companionless ornithologist searching for black storks along a river fjord. Played by French rising star Paul Hamy, Fernando is a slender and chiseled specimen, like the world’s most blasphemous religious statue.

The first 20 minutes charts Fernando’s routine with tranquil and hypnotic tedium: he goes for an early morning swim, watches some birds, calls his boyfriend back home, takes his meds, and finally heads out on his canoe. On his trip, he spots his desired bird, only to lose control of his vessel amid oncoming rapids. Stranded on the riverbank, Fernando is found and revived by a pair of female Chinese pilgrims (Chan Suan and Han Wen), two self-described “good Christian girls” who are lost on their trek along Santiago de Compostela and recoil when Fernando, a non-believer, tells them, “There is no God.” The next morning, he awakens stripped, bound, and tied to a tree as the women announce their plans to castrate him with the depraved and gleeful conviction of two avenging angels.

Fernando ultimately escapes, but to divulge the rest of what transpires as The Ornithologist builds to its transformative finale would be to spoil everything that makes Rodrigues’ pluckily warped odyssey such a compelling cinematic experience, even – or especially – when the images presented seem to actually transcend immediate comprehension. Rodrigues provides plenty of inspiration to his longtime collaborator Rui Poças, who worked similarly indelible wonders in Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. In this film, the cinematographer finds plenty of unexpected positions and perspectives from which to visualise Fernando’s conversion to sainthood.

Completely in sync with Rodrigues’ direction and conception of this story, Poças’ images aim to capture the metaphysical in a natural world and he inflects the overriding tone of the piece in exceedingly inventive ways. He evades the self-aggrandising stoicism of, say, Emmanuel Lubezki’s work on The Revenant, instead offering a multifaceted and gently amusing vision of a lush and bewildering crossing, which encompasses everything from one comically direct close-up of morning wood to a handful of creepily voyeuristic shots that drift away from Fernando and immerse us within the POV of an owl and a dove.

Poças and Rodrigues rework Saint Anthony’s expedition with a bold concept that seeks to express the essence of an experience, rather than its physical reality. The Ornithologist is more illusion than gospel, free of any emotional underlining and emboldened by a frank and often brutal eroticism that allows for a lusty encounter between our protagonist and a deaf-mute sheepherder named Jesus. What transpires is a keenly arousing episode that, like Rodrigues’ most spine-tingling scenes, speaks clearly about the immutable intimacies and dualities of its holy origins.

Published 3 Oct 2016

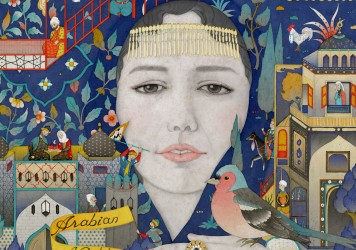

Enter the magical, mysterious world of Portuguese director Miguel Gomes’ three-part masterpiece.

This sublime Portuguese fantasia from director Miguel Gomes will likely feature heavily on best of year lists.

With his spectacular new three-part film, Arabian Nights, director Miguel Gomes proves himself to be a grand master of combining music and image.