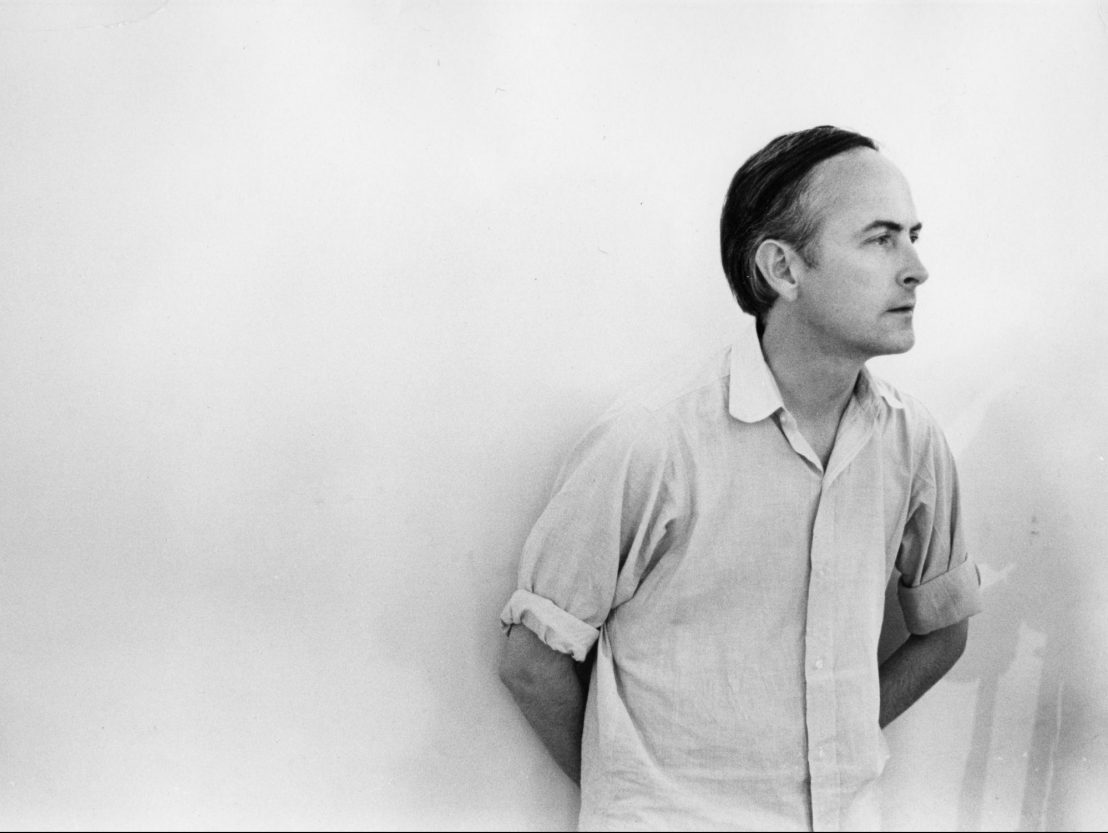

James Ivory reminisces about a youthful year spent in Afghanistan with this cozy archival documentary.

Marcel Proust gets a couple of mentions in A Cooler Climate, James Ivory’s memoir-film fondly reflecting on his salad days spent in Afghanistan during 1960. The 94-year-old filmmaker recalls reading In Search of Lost Time while living in Kabul to gather footage for a documentary that never came together, and notes that the doorstopper novel has become something of a madeleine for himself. In his own strained yet firm voiceover, he explains that Proust’s writing conjures the sound of braying livestock, which transports him right back to the riverbanks he captured on reels that then gathered cobwebs in his personal collection for decades.

It’s with a Proustian sense of wistful introspection that he dusts off this archival motherlode, a work of salvage ethnography redirected to more intimately personal ends. As the opening scene-setting states, he returns to Afghanistan before the political turmoil of the Taliban and the mujahideen – a balmy Eden with an innocence he can equate to his own as he searches for a home welcoming to him and his burgeoning sexuality.

Accepting of its own minor stature at a svelte 75 minutes helped along by Alexandre Desplat’s high-burnish score, the collection of restored filmstrips — at times wonky-looking in its digitally interpolated smoothness and queasy color — skirts many of the pitfalls one might presume of an aged white tourist reminiscing on their attachment to the Middle East. Aside from a diary excerpt recounting his extreme distaste for the food and its ruin wreaked on the digestive system, his tone is that of humility and gratitude for a paradise that took him in at a more directionless juncture of his life.

He allows the revelatory yet quotidian scenes of chores, prayer, and other doings of daily life to speak for themselves, piping in mostly to articulate his relationship to them. With the harrowing exception of one snippet that sees children frolicking in a swimming hole while tossing the severed head of a goat like a beach ball, he focuses on the familiar over the exotic, marveling at the organic ease with which he fit into it.

Ivory gains a counterpoint and a kindred in the journey of Babur, a 16th-century Afghan ruler making not-so-oblique reference to his male lovers in the journals circulated as literature today and sampled liberally in the narration. The intellectual wandering of the emperor begins a lineage of queer self-actualization into which Ivory tentatively fits himself, after recounting the difficulties of his own provincial youth in Oregon, where his boyhood wish for a dream house he could meticulously decorate made him an object of derision.

Portrayed as a paradisiacal sanctuary (if not for the unforgiving heat pushing Ivory’s constitution to its limit during an outing in a desert tent), Afghanistan gives to Ivory the same escape any traveler hopes to receive from a foreign country, its anonymity allowing him to shed his identity and begin the process of reinvention he’d complete with his transition into feature directing. The loose narrative hastily arrives at a conclusion with the introduction of Ismail Merchant, Ivory’s lifelong professional and domestic partner, their enduring love bringing a happy end to his wayward placelessness.

Destined to be gobbled up by blue-haired matinee-goers eager to share in the unadulterated nostalgia, the modesty of a project that combines the two chief schools of amateur cinema — home movies and vacation slideshows — works to its favor. Determinedly minor, the film excuses itself from stringent anthropology and endeavors only to show us the interior of one man’s inward-facing crisis. In the next century, we would have blogs for this; it’s a gift that Ivory’s navel-gazing takes such frequently lovely shape.

Published 11 Oct 2022

James Ivory and Ismail Merchant’s stunning 1987 love story prizes sensuality over intellectualism.

Luca Guadagnino’s scintillating follow-up to A Bigger Splash is a touchy-feely screen romance for our time and for all time.

By Katie Goh

My Childhood, My Country sees filmmaker Phil Grabsky and journalist Shoaib Sharifi capture a young man’s life.