Rejecting the physics of an ever-expanding comic book universe, Bryan Singer’s Superman reboot has passed the test of time.

About a decade ago, we were in the middle of the Big Bang in which all comic-book matter began to expand outward into what we now know as the various parallel and rival Cinematic Universes, those ever-more complex constellations of inter-film continuity and overseas presales. A “universe” implies not just the basic blockbuster promise of something for everyone, but something loftier, commensurate with the unearthly sums of money at stake. It’s not just a matter of packing a film with enough action, quips, symbolism and famous faces (“More stars than there are in the heavens,” went the old MGM slogan), but making sure that the universe keeps expanding, until it’s so big that nothing outside of it could possibly matter. “Universe” is the new “franchise” – a verbal tic betraying our insistence that these oxygen-sucking cultural behemoths are not mere products, but something profound. Something truly universal.

But 2006 was a long time ago, at least for superhero movies. Spider-Man was still a boyish novelty, the admonition “with great power comes great responsibility” still barely audible over the swoosh of his webs. Batman had just begun on the sturm-und-drang persuasively authored by Christopher Nolan’s fresh intellect. Marvel was still assembling the Avengers, frantically buying back the rights to its best-known characters from other studios. And that same year, director Bryan Singer, who’d gotten Marvel’s X-Men off the ground for 20th Century Fox, took on a single, iconic DC character in a sort of hybrid sequel-remake of Richard Donner’s original Superman films.

Warner Bros released Superman Returns on July 4th weekend. It was the first Superman feature in two decades. The film did… fine. It took in about $400 million worldwide, earning back its budget. But Warner Brothers scrapped plans for a sequel, with one studio exec griping that the two-and-a-half-hour film didn’t feature enough violence (you know, for the kids). Warner Bros rebooted Superman in 2013 in the shape of Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel, taking the character in a “darker” direction clearly inspired by Nolan’s Batman films. The studio finally achieved liftoff of their long-planned DC cinematic universe when Snyder’s Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice hit theatres in 2016.

If Warner Bros seems more behind Snyder than Singer, despite BVS receiving comparatively unfavourable reviews, it’s perhaps because Snyder offers a stronger “take” on Kal-El: his films are recognisably grey and self-serious; lugubrious and violent. Superman Returns offers a traditional big-tent version of the character – though no one knows precisely why it didn’t galvanise the world the way Superman used to, and the way that Hollywood circa 2006 could see that comic-book products were beginning to again. Although many critics liked (but didnt love) Superman Returns, the consensus among those who didn’t was that it was overly dutiful, ponderous and generally overawed by the whole Super-mythology. (Again, 2006 was a long time ago for superhero movies – they had no idea how bad it would get.) Meanwhile, fanboys found Superman Returns too meta, too revisionist, too safe.

In the run-up to Batman V Superman, Snyder explained away negative responses to Man of Steel as the resistance of hardcore fans who didn’t want to see a vision different from their own. Here, the strain of a career in customer service – which is basically what blockbuster filmmaking is – begins to show. Today the vast majority of mainstream releases pitched to a predominantly male audience are based on preexisting properties, considered safe investments because they come with built-in fanbases. This audience is thus empowered to lobby, vocally, that the movie they’re being depended on to pay for will indeed be the movie they want. Studios go to great pains to assure fans that they’re on their side: they value the same things they do about these beloved characters and everyone’s on the same page about how important it is that this story be told the right way.

Superman Returns is a movie about fan service – about what myths owe their public. A film in ambivalent awe of itself, it palpably strains to live up to impossible demands: for comic-book zip, American Century allegory, and enchantments at once comfortingly familiar and newly thrilling; it’s a film like its hero, an Atlas whose shoulders are beginning to buckle. A self-consciously classical Superman story, the film is committed and self-deprecating, hitting the marks laid down by the original and most primal comic-book archetype – and also the most earnest.

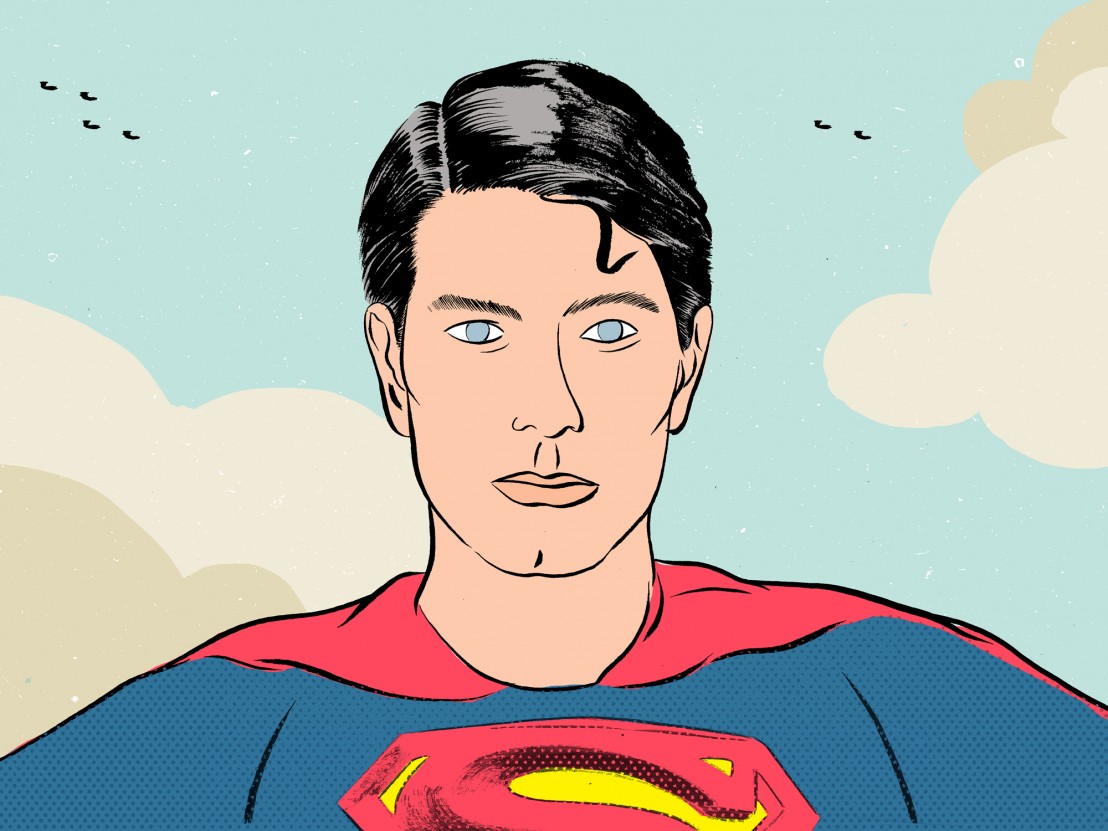

There are cornfields and crystals, billowing red capes and thick black glasses. There’s John Williams’ triumphant score and even an unknown star, Brandon Routh, who looks like Christopher Reeve (who had died in 2004). The film features grandiose religious themes, and the voice of Marlon Brando as Superman’s father. Its palette is bright, sky blue and sun yellow. It’s also tender and melancholic, almost mournful, about its superhuman celebrity and saviour. The film can hardly be said to succeed on its own terms, because it doesn’t have its own terms – but 10 years on, Superman Returns seems both wittier and wiser than any subsequent attempt to fulfil or interrogate the demands of the superhero film cycle.

In Superman Returns, Superman literally returns to Metropolis after five years of soul-searching in space, to find Lois Lane (Kate Bosworth) shacked up with a new fiancé (James Marsden), the Pulitzer-winning author of the article ‘Why the World Doesn’t Need Superman’. Whether or not he’s an outdated incarnation of “truth, justice and the American way,” though, he’s soon enough tearing open his dress shirt and taking flight, to rescue an out-of-control jetliner and land it safely in a baseball stadium, and reassure the passengers with a corny joke. (This is one step in Lex Luthor’s devious plan; the sequence begins in a basement as he and his henchmen mess with an elaborate toy train set, and escalates from there.) When he next takes to the air again, he descends to visit Lois’s house, and levitates outside, alone. He flies so gracefully, light and lyrical.

Singer seems to have found his level in comic-book adaptations. He has an eye for splash-panel compositions, here fitting Superman’s fist-forward flying pose across the length of his widescreen frame. His better films mix campy performances with an epic sweep that’s childlike without being condescending. The actors in Superman Returns get it right: Routh’s gentle voice is counterbalanced by Kevin Spacey’s supercilious pauses, and Parker Posey’s blaring boredom, as Lex’s sidekick. The action set pieces are clever and the camera never loses its sense of scale. Most potent is the moment when Superman, having carried a massive hunk of Kryptonite up into space and hurled it out of Earth’s orbit, collapses, exhausted from his superhuman efforts, and lets gravity take over. As he descends, Singer’s symmetrical wide shots and the sea of extras gape in astonishment at the man who fell to earth.

What do you think is the greatest blockbuster of the 21st century? Have your say @LWLies

Published 13 Jul 2016

Twelve writers pin their colours to the tentpole in our survey of the best summer movies of the modern era.

By Tom Bond

It’s become increasingly rare for films like Batman V Supeman: Dawn of Justice to live up to expectations.

By Ceri Thomas

The story of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster is the most inspiring and depressing in the history of the comic-book industry.