The Wachowskis’ pricy paean to juvenilia is a glorious multi-coloured folly which stands in stark contrast to its blockbuster brethren.

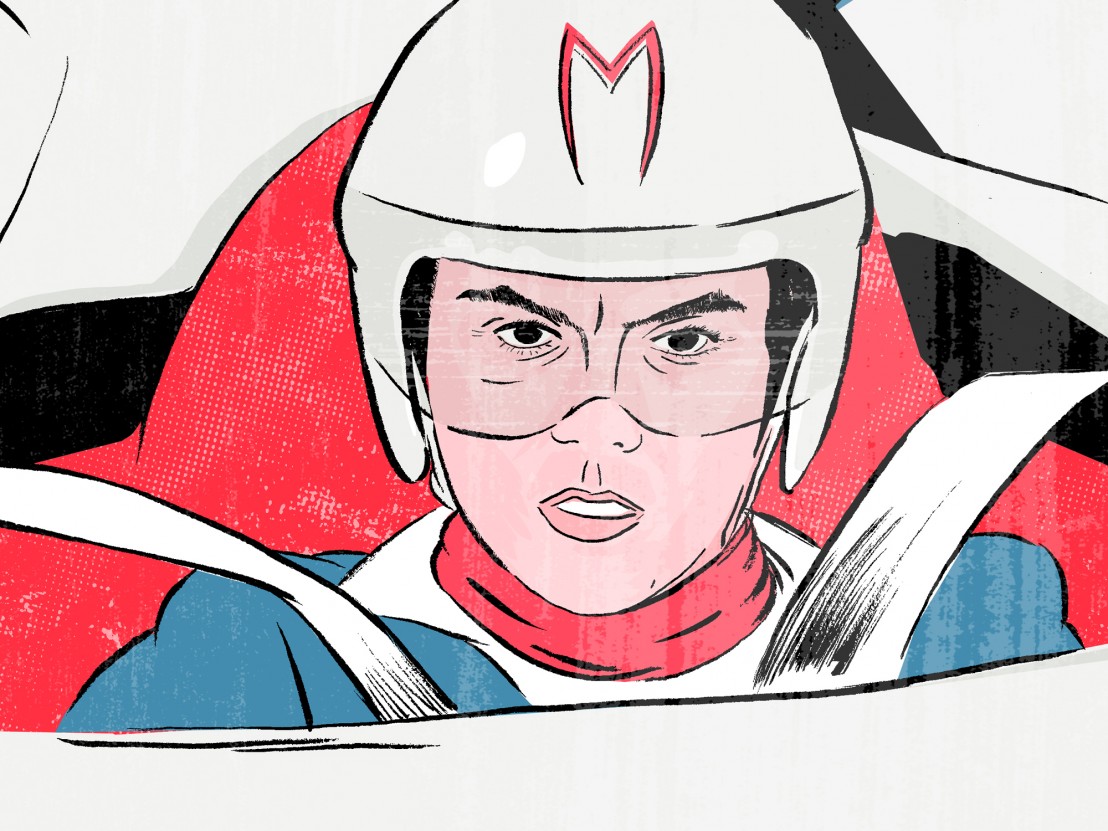

A “blockbuster” only in the theatrical sense, Lana and Lilly Wachowski’s Speed Racer was largely shunned by audiences upon its release in May 2008. The critics weren’t much kinder: Slant Magazine’s Nick Schager called it, “hyper-digitised Skittles soup”; Alonso Duralde of MSNBC invited viewers to, “imagine someone pouring hot, melted Starburst candies into your corneas”; and Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers put it that the Wachowskis, “projectile-vomit their cotton-candy dreams all over the big screen.” Another common criticism shared by both detractors and many of the film’s fans was its 135-minute runtime; certainly lengthy for what is generally considered a kid’s movie. AO Scott wrote in his New York Times pan that Speed Racer, “is about a boy driving a car, surely a subject that cries out for linearity, simplicity, velocity.”

Sadly, Speed Racer was faulted for its formal and narrative ambitions in the same summer that saw the commercial and critical dominance of two comic-book films – The Dark Knight and Iron Man – which set the regrettable templates of the self-serious and the “cinematic universe” blockbusters respectively. While most like to propagate a Christopher Nolan/Marvel binary amongst these kinds of films, in reality they’re cut from the same prosaic PG-13 cloth. The former’s idea of formalism is occasional high-resolution aerial shots and pseudo-philosophical monologuing, while in the latter’s case, Robert Downey Jr’s constant quipping and some inert CG robot battles account for buoyant pop filmmaking.

But with neither tenuous War on Terror allusions nor brand management on its mind, Speed Racer stood in opposition to this burgeoning blockbuster Tradition of Quality. Using an intellectual property to make an anti-corporate statement (albeit a contradictory one, being on the Time Warner bankroll), the film is not so much an attempt at elevated juvenilia as it is about juvenilia.

We open on the adult Speed (Emile Hirsch) anxiously tapping his foot pre-race, only to quickly flash back to his younger self (played by Nicholas Elia) in class. From the get-go he has one thing and one thing only on his mind: racing. The film whizzes in and out of flashback sequences (the presence of Raúl Ruiz regular Melvil Poupaud as a race commentator provokes the comparison with the Chilean director’s yen for tangental narratives), not so much transitioning as sliding between scenes; heads rolling from one background to another, as if there’s no barrier between each new digital landscape.

The Wachowskis went to unprecedented lengths to match the original look of the ’60s cartoon, shooting foreground, midground and background separately, then digitally compositing everything together in post-production to achieve a seemingly endless depth of field. All this amplifies the melodrama at the heart of the film; the death of Speed’s older brother, Rex (Scott Porter). Returning to that opening sequence, we see Speed in the middle of a race driving alongside Rex’s ghost as he risks breaking his record – a thrilling set piece that establishes the film’s emotional stakes. Despite Speed being the title character, the film is really an ensemble piece about his family unit: Mom (Susan Sarandon) and Pops Racer (John Goodman), Speed’s younger brother, Spritle (Paulie Litt), his pet monkey, Chim-Chim, and girlfriend, Trixie (Christina Ricci).

Later, the conglomerate Royalton Industries tries to seduce Speed into singing a contract to join their team, even though it’s clear he won’t budge from his family-run independent Racer Motors. While Spritle and Chim-Chim initially seem to faction as the de facto comic relief for younger viewers, eventually we come to see them as an ideological pinpoint. A hard cut from Royalton’s utterance of “money” to a sugar-rush addled Spritle air-guitaring to ‘Freebird’ in the company headquarters – it’s the Wachowskis’ earnest idea of anarchy, present in the rambunctious antics of child and monkey.

Yet Royalton’s speech isn’t just about capital. Cruelly, he reveals to Speed that every great race was fixed and the heroes that adorn the posters on his bedroom wall were all part of the façade. From this point on, the film’s drama expands from the weight of legacy to regaining passion for one’s vocation in a world that constantly seeks to dilute it for capitalist gain. While money remains an abstract notion within this cartoon world, the Wachowskis, who dared to conclude their ultra-sleek Matrix trilogy on the image of a utopia, turn this child-like optimism into a political statement.

By the time the film quotes “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite” from 2001: A Space Odyssey as Speed crosses the finish line in the climactic scene – exploding cars coalescing into a stream of colours – there’s a feeling that the directors are throwing a jubilant middle finger to their critics. And while it would be tempting to call the film the Blade Runner of its time, nearly a decade later there’s little trace of Speed Racer’s influence on cinema (or rather advertising, which served in the case of reclaiming Ridley Scott’s 1982 film maudit). Yet perhaps Speed Racer’s perceived failure vindicated its radical stance? Its visuals are too singularly unique to be co-opted, its message too honest for anyone other than the Wachowskis to believe in. Its victory wasn’t to sell more, but simply the fact that it actually got made.

What do you think is the greatest blockbuster of the 21st century? Have your say @LWLies

Published 13 Jul 2016

By Anton Bitel

In Christopher Nolan’s urban epic, Batman takes on The Joker… or should that be, George W Bush takes on Osama Bin Laden?

Not even Channing Tatum and Mila Kunis are enough to save the Wachowskis’ gnarly, garish space opera.

Twelve writers pin their colours to the tentpole in our survey of the best summer movies of the modern era.