Key members of The Simpsons’ creative family share the inside story of the show’s cherished Halloween specials.

The Simpsons’ latest Treehouse of Horror episode opens with a familiar joke. Lured to a foggy seaside town by a guidebook titled ‘10 Places to Visit Before You Mysteriously Disappear’, the titular family discover they’re to be sacrificed to an ancient ocean god (“Spongebob?!” asks Homer). The mythical monster Cthulhu then rises from the deep, and Homer challenges him to an eating contest to determine his family’s fate. Of course, Homer out-eats the giant Lovecraftian sea creature, because – like the haunted mansion of 1990’s inaugural Treehouse, which sought to spook the family but ended up self-destructing to avoid another spend another second in their company – the Simpsons are often more beastly than whatever is meant to be terrorising them.

It’s a twist that has made for some of the show’s best-loved Halloween specials. In 1996’s ‘The Thing and I’, the family are tormented by Bart’s malevolent secret brother, only for it to be revealed that Bart is the true evil twin. “If you wanted to make Serak the Preparer cry, mission accomplished,” blub the Simpsons’ alien abductors in another early favourite, ‘Hungry are the Damned’, after the family’s bad behaviour costs them their ticket to an outer space paradise “a thousand times greater than what you call ‘fun’.”

As Lisa puts it at the end of that story, “there were monsters… and truly we were them.” That sentiment could just as easily be applied to 1993’s ‘The Devil and Homer Simpson’, in which Satan (a goat-legged version of evangelical neighbour Ned Flanders) sells Homer a doughnut in exchange for his soul. Here, Homer proves more duplicitous and full of sin than Lucifer himself. Presented with “all the doughnuts in the world” by Hell’s “ironic punishment division”, the demon in charge of his torture looks mystified as an insatiable Homer keeps eating and eating. “More!”

For 29 years, Simpsons fans have been devouring Treehouse parodies with a glee not unlike Homer in that doughnut-feeding torture machine. “It’s people’s favourite episode that we do every year, the biggest event that we do,” says executive producer Al Jean, who has worked on every one of the show’s record-breaking 30 seasons. Guillermo del Toro, who created a terrifying spin on the famous opening couch gag sequence for 2013’s Treehouse of Horror XXIV, agrees: “It’s often my favourite episode of the season. Some of my favourite Simpsons images and moments over the years come from there.”

When The Simpsons first aired in 1989, it became an overnight phenomenon for its honest portrait of a flawed, dysfunctional nuclear family. Treehouse – which debuted three episodes into season two and has been a mainstay of the show ever since – went about amplifying that dysfunction to often violent extremes. By the time The Simpsons were parodying The Shining in 1994’s Treehouse of Horror V, instead of throttling members of his family, Homer was chasing them with an axe.

Macabre riots of smart cinephile homages to horror films old and new, from Hitchcock classics to schlocky VHS chillers that time forgot, Treehouse quickly became an ingrained part of the Halloween pop culture calendar as The Simpsons’ popularity bloomed in the early 1990s. “Here you had a family comedy that right out of the gate was one of the most beloved shows in TV history. Then three episodes into our second season, we’re doing this absolute horror show,” recalls Mike Reiss, another of the longstanding creative forces behind the show. “Maggie’s head is spinning, family members are murdering each other… it was a real leap of faith that broke all reality of the show. It was an astounding thing.”

So how did the biggest family show in America end up, by its bloody mid-’90s peak, bringing cannibal school teachers, killer clown dolls, post-apocalyptic mutants and flesh-eating fogs to primetime TV? Did its barrage of riffs on horrors from across cinema history inspire a new generation of viewers to explore the genre? And exactly how is Treehouse in part responsible for Shrek? According to Simpsons writers, animators, producers and critics, it all started with a comic.

The decade or so preceding The Simpsons saw “a real transformation” in horror cinema, remembers Jean, at the time a student in Boston. His local cinema, the Harvard Square Theatre, used to show two films a day (“Which was fantastic; well, not so fantastic for my grades”) and it was here Jean observed a sea change in the genre that primed America for its first Treehouse. “Horror movies used to be known as B-movies, the kind of things you would watch on Friday nights when you were sleeping over at friends’ house or whatever. But movies like The Exorcist in 1973 – one of the finest movies ever made, period – and Halloween in 1978 launched a whole new era of horrors that were higher budget and scarier and made by A-list directors. The 1980s were very different for the genre.”

“It was a sort of golden age for horror in America,” says Reiss. “They seemed to be giving you a new Freddy Krueger every week. Man, I loved those days.” As The Simpsons began to take shape, Jean, Reiss, creator Matt Groening and the rest of the show’s core creative team bonded over their shared passion for slashers, taking group trips to the cinema to see Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead II and the Nightmare on Elm Street sequels. “There was an almost universal love of horror at The Simpsons,” explains Reiss. “We were all unmarried men in our twenties making the show. Of course we all loved this stuff.”

Showrunner Sam Simon had in his office a collection of EC Comics, famous for its ‘Tales from the Crypt’ and ‘Weird Science’ anthologies of strange and sinister horror vignettes. Those comics were a product of market research suggesting soldiers who served in World War Two no longer wanted caped crusaders, craving sex and violence in their reading material instead. “The idea was to do something that emulated those comics,” recalls animator David Silverman, one of the three directors responsible for the first Treehouse. “Kang and Kodos, the slobbering aliens in the second segment of the first Halloween special, were ripped straight off one of the covers.”

Pairing the outlandish tales of EC with the otherworldliness and irony of the Twilight Zone and Stephen King, the first Treehouse episode – a trio of parodies of famous horror narratives, setting the framework for every subsequent Simpsons Halloween special – was notable for its daring closing spin on the Edgar Allen Poe poem ‘The Raven’, narrated by Darth Vader himself, James Earl Jones. In it, Homer portrays the poem’s grieving protagonist, slowly maddened by a mischievous talking bird (Bart, obviously). “It was an experiment, but then the whole show was an experiment then,” says Reiss.

“It’s my understanding that right away, audiences just really embraced it,” says writer and consulting producer Carolyn Omine, who joined The Simpsons in its 12th season, penning 2000’s ‘Night of the Dolphin’ segment and all of Treehouse of Horror XXII in 2011. “Just as well, really, because they are seriously tough to make. The Halloween episode tends to need a really long lead time. It always takes at least nine months to write and animate an episode.” Silverman estimates that they require “three times the amount of design work” than a regular episode.

“It’s brutally hard on the animators,” agrees Reiss. “Say one story is a Jack the Ripper parody. All of a sudden, the animators have gotta redesign everyone in Springfield. What does Chief Wiggum look like in the 18th century? What does Homer wear? What does the 18th century version of their home look like? Everything’s gotta be redesigned. ‘The Simpsons are at a Halloween party’ is seven words for me to write, but demands a crazy amount of thinking and invention to design. What costumes are they all wearing? If Bart is dressed up as a droog from A Clockwork Orange, it might take several attempts to nail, unlike every other episode, where we already know what everyone looks like, what all the locations look like.”

Part of Treehouse’s sparkle is down to the creative freedom it was afforded from the get-go. “When The Simpsons was first created, Fox was a young, struggling network,” says John Ortved, author of ‘The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History’. “James L Brooks, the exec producer, could not have been more powerful in Hollywood. For Fox to get Brooks to bring them a series was a very big deal. They weren’t gonna try to mess with his stuff. The studio might have given notes but The Simpsons didn’t look at them.”

“We were completely left to our own devices,” says Omine. “I’ve worked on other shows where they’re inundated with ‘what does the research say’ and all that. ‘Woah, you haven’t used the catchphrase by that character!’ If you try to guess what the audience might find funny and interesting, that’s when you run into trouble. Instead, we were allowed to run riot. That came in handy with Treehouse, for sure.”

It certainly did: the resulting Halloween specials were free to be thrillingly adventurous. Regular Simpsons narratives rifled through pop culture references at a ferocious pace. The way Treehouse abandoned the rules, logic and style that normally governed over Springfield allowed the show to lay references on even thicker and faster than usual, occasionally getting impressively obscure with these nods. “Treehouse IV parodied Rod Serling’s Night Gallery – a homage not a lot of people would have understood at the time,” says Silverman. “There was another parody of David Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone we did called ‘The Ned Zone’, which probably had a few people scratching their heads too. The rule was, even if the audience don’t notice it or understand, they’ll feel it.”

Pre-internet, without fan forums, Reddit and the like to immediately interpret these episodes’ myriad homages, the effect was magical, suggests Jean. “It’s funny. Now you can go online and get the whole thing broken down for you and watch the original clip being referenced in two minutes. It was a foreign concept back then. It had a bit more mystery to it.” Reiss calls these references “little timebombs. It’s a very common thing for people to see something on The Simpsons and 20 years later see the actual thing we were parodying. I love the idea that people see something first and it sticks in their head.” Omine says she can imagine Treehouse episodes becoming gateways for young people into horror: “Generally, what happens is either people go, ‘Oh, they’re parodying that thing I love’ or they’ll be like, ‘They’re parodying something I don’t know, I ought to check that out.’ We’re very happy about that.”

Free of the stylistic and canonical constraints of regular episodes, in which “people could die, have limbs chopped off without a second thought,” as Omine points out, writers’ imaginations went wild as each instalment became more hotly anticipated than the last, verging into experimentation and often meta commentary. Treehouse has been the place over the years The Simpsons has been most self-reflective on its own place in pop cultural landscape.

In 1991, the hugely popular Monkey’s Paw story delivered not only some of Treehouse’s funniest ever lines (“Homer, there’s something I don’t like about that severed hand”) but also a hilarious swipe at the show’s own cultural and commercial saturation. At the peak of Bartmania, as Fox’s merchandising machine went into overdrive and Simpsons toys, lunchboxes and everything in between filled store shelves across America, the episode saw Bart use a magical monkey’s paw to wish fame and fortune for the family. “They used to be cute and funny but now they make me sick,” complains a character as the family’s novelty calypso albums and overpriced t-shirts (“18 bucks for this?! Forget it!”) becomes a plight on society.

Elsewhere, segments have made complex critiques of American consumerism. The story ‘Attack of the 50ft Eyesores’ sees advertising figures come to life, rampaging across Springfield. They’re defeated when Lisa helps write a jingle advising terrorised citizens: “Just don’t look, just don’t look.” Ortved claims that story contains, “Deep truths about capitalism and marketing that I think about all the time today. We’re at a point where negative and positive attention are really equivalent in the media. If you do something bad, you get to become a millionaire. If you brag about sexually assaulting women, you get to be president. What’s good attention and bad attention with social media and the way we see media now, there’s really a thin line, if there’s any line at all. The truth they instil into this tiny little joke is that the only way to triumph over that is to give it zero attention.”

‘The Shinning’ – a spin on Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 horror that’s regularly voted the best Treehouse story ever – apparently won the seal of approval from the director himself in 1994. “After he died, we found out he got a case of The Simpsons delivered to him,” says Jean (a lengthy tribute to Kubrick followed in Treehouse XXV a year later). In the same episode, Bart and Lisa uncover a plot to cook unruly Springfield Elementary students and feed their remains to other pupils in one of the most chilling segments in Treehouse history. This was all down to that era’s showrunner, David Mirkin, who – rebelling against television regulatory board the FCC, who were in the midst of a crusade to curb cartoon violence – filled that year’s show with as much violence as possible. “He loved dismemberment and gore,” recalls Jean, “I remember us thinking, ‘Oh, he’s going a little too far here.’ But it obviously ended up so great.”

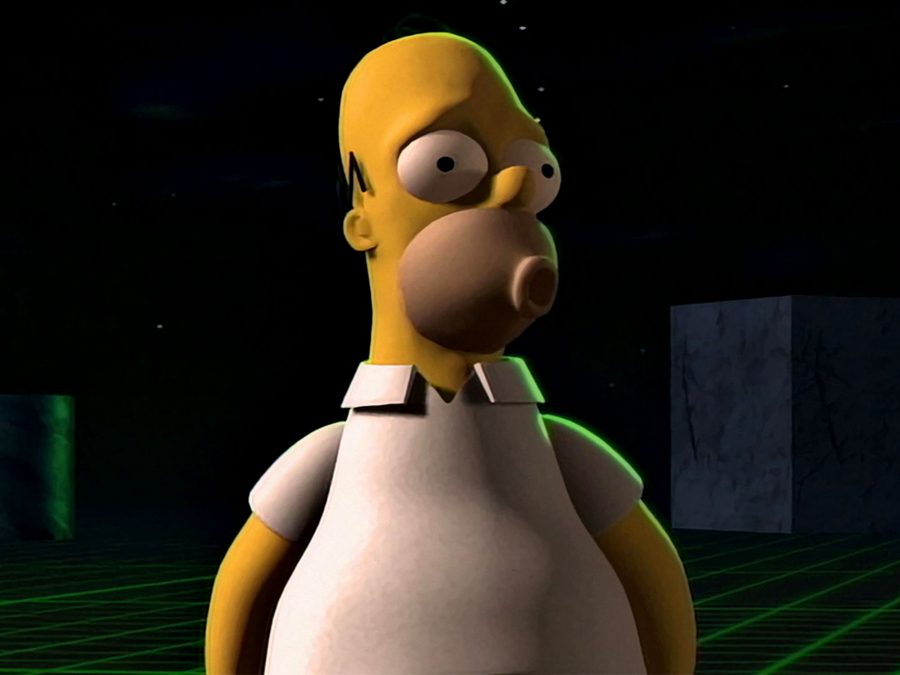

Then there’s ‘Homer Cubed’, which famously sees Homer escape into an alternate, CGI dimension to avoid Patty and Selma. The segment landed a month before Toy Story was released and, in a strange twist of fate, had a hand in the rise of DreamWorks Animations. Intent on creating a CG animation after seeing a Dire Straits music video, Silverman was able to enlist a company called Pacific Data Images, who provided the then cutting-edge computer graphics for free as an advert for their company. It worked: DreamWorks later acquired PDI, leading to a spate of CG animated films including Antz, Shrek and Kung-Fu Panda. (Silverman, incidentally, went to work for DreamWorks’ rivals Pixar, co-directing Monsters, Inc. in 2001).

These Halloween stories worked because although Treehouse broke from the style and continuity of regular Simpsons episodes, it never undermined or upended its characters. It makes sense when Marge falls in love with Homer in 1992’s King Kong parody, because when isn’t Homer an oversized ape who Marge finds a way to love despite his rampaging id? Even the Treehouse of Horror V alternative reality in which Flanders is the overlord of earth rings true to that character: when he greets his army of minions, he does so with a cheery “hidely-ho, slaverinos!”

But finding those stories – horror narratives that the characters we know and love can authentically fill – has become harder over the years. The writing staff, Reiss insists, don’t want to just churn out Simpsonised versions of whatever blockbuster horror made a splash at the box office that year. “The movie It is about a scary clown, and we’ve got Krusty – but we didn’t do it. We don’t try and jump on the obvious thing.” The advent of the internet, meme culture and YouTube is a factor here. “We didn’t want to parody that because by the time we get our parody out, everyone will have parodied it.”

Back in the show’s early days, continues Reiss, “It used to be very fun because we just had the whole world of horror to choose from. We’d say, ‘Okay, let’s make fun of this beloved old movie here, let’s do that beloved Twilight Zone episode there, then maybe we’ll do an original thing.’ But I really think we’ve kind of scraped the earth now. We’re writing our 30th one now. Thirty times three segments per episode? That’s 90 archetypal horror stories we’ve had to come up with. It just gets harder and harder, and when I see what we wind up parodying sometimes, it’s like, ‘Alright – we’re out of ideas, folks.’”

It’s easy to understand Reiss’ sentiment, and tempting to extrapolate it to the show as a whole (accusations of declining quality and imagination have dogged The Simpsons since roughly its 10th season). This year’s Treehouse also featured parodies of M Night Shyamalan’s Split, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Jurassic Park, receiving low viewing figures (19 per cent down on 2017, according to Deadline) from the public and despondent sighs from critics. As Dennis Perkins wrote in The AV Club: “More often than not in these late days, the yearly Treehouse of Horror functions less like a gleefully disreputable comedy recess for writers looking to experiment with their less-reputable ideas than just another obligation to fill out The Simpsons’ never-ending 23-episode season mandate with some genre-specific pop culture references.” This review and others like it allege that the fact the films being spoofed are barely horror films is proof that Treehouse is feeling tired. This accusation is nothing new for Omine.

“In 2011, I wrote a very controversial parody of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, about a man trapped in his own body. The movie’s not an actual horror movie but it is horrifying,” she says. “That was this weird arthouse movie and I feel like our version was very touching: Homer can only communicate through farting but finds himself able to say things to Marge that was never able to say through words. Some very angry fans confronted me about why that wasn’t a horror movie soon after.”

Reiss also feels this is unfair. “Lists on the internet downgrade Treehouse segments that aren’t from that genre: like, hey, Transformers is not a horror movie. Well, hey, we know!” He points out that ‘Time and Punishment’ – not only a classic Treehouse story but an all-time classic Simpsons story – in which Homer accidentally invents a toaster that can zap him through time, is more sci-fi than horror, but is still raved about on the same lists.

Ortved has another theory as to why Treehouse might seem less potent in 2018. “For the first seven or eight years or so, The Simpsons had to be pretty tied to reality. There were rules to that universe. If Homer fell down a hill, he had to be really hurt. In later seasons, the Simpsons became unmoored from that. I think of the new introduction to the show, which debuted about 10 years ago or so, the bullies are sawing the head off a statue that falls onto Ralph’s head and he walks away kind of confused. I think that shows the entire devolution of the show from that reality. At the beginning of the series they had an episode where Bart had to remove the head of that statue and had to do it with a saw and lug it around town and it was this huge heavy thing.”

His point is that the boundary between the fantastical Treehouse of Horrors and regular Simpsons episodes has become blurred, taking away the novelty of these Halloween specials in which the impossible is explored. “There used to be rules to The Simpsons,” says Ortved. “Once a year with Treehouse they got to play with those rules. They could do things they couldn’t normally do, which I think is what made them fun for the writers and fun for the viewers. I’m not sure that’s there now.”

Criticism of ‘New Simpsons’, as everything after season 10 is referred to by fans, overlooks a lot of memorable Treehouse moments: a twisted 2017 segment, ‘Mmm Homer’, in which the character develops a cannibalistic taste for his own flesh (“it was just this strange, very, very disturbing idea,” remembers Jean), and del Toro’s reference-packed opening sequence in Treehouse XXIV to name a few. “For me, as a Simpsons fanatic, that was a dream come true,” says the Pan’s Labyrinth and The Shape of Water director. “I had been campaigning for a small cameo as Bumblebee Man’s brother from Guadalajara. This was even better. Treehouse had not had a couch gag ever. So I suggested to Al and Matt that I design a bizarro world one in which we hit the same beats as the normal one but twist every gag around.” The result was a “love letter to classic monsters,” he explains.

Will The Simpsons’ showrunners ever decide to make Treehouse, in the words of Bart’s raven, “nevermore”? Jean says it’s unlikely. “Treehouse 30 will be episode 666. It’s worked out so perfectly – it’s insane. After all these years and all the permutations, it’s worked out that way. Crazy. I’m still excited for the Halloween show every every year. And I find that The Simpsons works if there’s problems in the world that are affecting families and unfortunately that’s gotten worse instead of better. Good for the show, bad for humanity.”

Reiss is similarly upbeat about Treehouse’s future, despite the struggle involved in continuing to create them. “Fans love it, and as hard as they are to do, at least we go, ‘Alright, that’s what one episode of the Simpsons is going to be this year.’ A lot of people try to think of us as artists, or think of the show as ‘crafted.’ But to me, it’s always a 22-minute hole that we shovel jokes into every week. And we’ve got 22 graves we gotta fill in every week. It’s nice to know one of them is going to be the Halloween show.”

Ortved also sees no end in sight for The Simpsons or its forays into horror, though he thinks it’s possible that one day it may transcend the 22-minute TV show format. “I wrote in my book that The Simpsons will be like Mickey Mouse. There’s already a Simpsons land theme park area, at Universal Studios. I think eventually they will live as this pop culture touchstone that’s maybe not as big as Mickey Mouse. I’m not smart enough to know what the future of media will look like, but I know they will be iconic within that, and Treehouse of Horror will be part of that legacy.”

Until then, expect the doughnut-feeding torture machine-like deployment of Treehouse of Horror episodes to continue, and for them to continue to be a driving force of what makes The Simpsons a prime time TV institution in its 30th year and beyond. “Believe me,” says Jean. “If I could do 22 of them a year, I would.”

Published 26 Oct 2018

By Greg Evans

The tragicomic tale of Frank Grimes from 1997 contains a sharply-observed social critique.

The great Guillermo del Toro talks about his magnificent Gothic ghost story.

By Tom Williams

The stand out episode of the third season underscores the show’s uniqueness and unpredictability.