The movie car chase almost as old as the medium itself, so it was always going to be tricky picking out a mere 30 favourites. Ranking them on top of that is just asking for trouble. But, to celebrate the release of Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver, we thought we’d do just that. The director himself has cited several of the below films as key influences on his high-octane latest – but how many have made it into the business end of our list?

Maybe it’s cheating a little to start our countdown with a motorbike chase, but it didn’t feel right to leave out one of the great cult road movies. A diminutive copper (Robert Blake) is in pursuit of a bike gang, cuing a chase straight out of the Peckinpah playbook. While most chases remain about the need for speed, director James William Guercio nails the slo-mo better than the Wachowskis ever did.

The stunt-jumps (into conveniently placed piles of cardboard boxes) are certainly impressive, but the central chase in this Jackie Chan vehicle remains pretty conventional. Until its final moments, that is. Pursued by cars and motorbikes in a concept Mitsubishi, Chan and his plus one find themselves trapped between two vehicles on a bridge. Cue an escape of Bond-level ’80s preposterousness. We won’t spoil it here, but check out the clip below…

The Busby Berkeley of iconic car chases sees a trio of Mini Coopers take to the streets of Turin for some synchronised manoeuvres over unexpected surfaces. The editing kills the buzz long before that bloody song does. A trio of cocksure drivers in red, white and blue, rampage through a European city with plans to steal its gold, before their hubris sees them dangling off a cliff and out of ideas. As Brexit metaphors go…

A decade before Steve McQueen burnt rubber through the streets of San Francisco, Don Siegel ended this cracking noir with a race towards the Golden Gate Bridge. Shots from inside the vehicle – where snarling dope-smuggler Eli Wallach holds a mother and daughter hostage – make surprisingly effective use of rear projection, but it’s the expansive location photography on and around the under-construction freeway that disavows its B-picture credentials.

It may be the worst entry in the series, but the Wachwoskis still show a dab hand when it comes to the set-piece. A specially-constructed freeway sets the stage for the film’s extended chase sequence, thrillingly structured as a series of escalating sub-scenes. Naturally, the practical stunt work proves more adept at quickening the pulse than incessant slo-mo and CGI. The gravitational law-breaking may not have aged all that well, but the sheer scale continues to impress.

This one certainly lives up to its name. A prime slice of Italian exploitation from the director of Zombie Holocaust, the chase scenes in Violent Rome have to be seen to be believed. Seemingly shot on the hoof, tearing through the streets of the Italian capital at breakneck speed, the tension is drawn less from the quality of the direction than a palpable nervousness for the safety of the actors.

“All the time I thought I’d get killed, that someone might get killed,” says one stunt man of The Man from Hong Kong in the 2008 documentary Not Quite Hollywood. An Australian-Hong Kong co-production, with fight scenes choreographed by Sammo Hung, the minimal regard for safety concerns is readily apparent in the chase sequences. The whole film is one big rough-n-tumble, but the final vehicular dust-up merits inclusion on this list.

One of the great low-budget Italian crime thrillers from the 1970s, this suitably grim exercise in economy from Fernando di Leo pulls few punches in its bonkers car chase. All sweaty close-ups and pedestrian casualties, it peaks with an in-flight punch-up through a van windshield as small-time pimp Mario Adorf clings to the front. Pulp fiction at its finest.

Lacking the existential pose of either Vanishing Point or the more woozily heady Two-Lane Blacktop, Dirty Mary Crazy Larry stumbles towards capturing some kind of meaning from its nihilistic wipeout of an ending. Roughly hewn – for better and worse – it may not be quite as deserving of its iconic position in the annals of the road movie, given its inability to take much of a position on anything beyond Peter Fonda’s “All you gotta be is willing to take it to the max.” Still, it wears its fender-bending credentials well, not least in the final helicopter chase.

Unable able to squeeze an original-beating chase into his sequel to The French Connection, John Frankenheimer attempted to go one better on the streets of Paris some two decades later. It’s a valiant effort (in an otherwise lacklustre film) that benefits from expansive access to the city streets. If the interior shots don’t entirely meld with the stunt-driving, the low-angle vehicle POVs provide an exhilarating sense of pace.

A year after Michelangelo Antonioni blew the ’60s to hell with Zabriskie Point, Barry Newman drove a white Dodge Challenger through its dying embers in Vanishing Point. Vaunting its allegorical credentials more aggressively than Monte Hellman had in the superior Two-Lane Blacktop, its zen-like approach to the open road finds greater success when it shuts up and drives than in any incidental interruptions. Still, when the chase is on…

One could spend days trawling through the ranks of Italian exploitation cinema, unearthing car chases that put their American counterparts to shame. This doozy sees a Mustang and a Buick take to the streets of Ottawa for a balletic demolition derby. The film itself is standard poliziotti fare, elevated by this late sequence, as the motors chase and dance, smash into each other and soar impossibly through the air (and a train).

Clearly an inspiration for Ronin’s Paris-set chase, this nine-minute gonzo short from Claude Lelouch may not be a chase per se, but remains every bit the cinematic petrolhead spectacle. Shot at 5.30am in a single take, Lelouch careers through the streets of Paris. He later confessed to the car being his own Mercedes, over-dubbed with the sound of a Ferrari’s engine. Who cares? It’s pure, kinetic cinema.

Dad Movie 101 perhaps, but Bullitt is a pretty dull affair. At least there’s the chase – one of the most iconic in cinema history. San Francisco’s singular topography plays a big part, as does Lalo Schifrin’s stunner of a score, notable in its absence from the first screech of tyres. The commandeering of vast swathes of the city lends scale, while Steve McQueen’s shared duties behind the wheel of the Mustang ensure suitably energised interiors.

While the titular job refers to the Great Train Robbery, it’s the opening gambit of Peter Yates’ superlative British gangster flick that concerns us here. A jewellery heist goes to plan until spotted by the coppers, resulting in a hurtling chase through the streets of ’60s London. Shot by Douglas Slocombe, it’s one of the great London chase scenes, and led directly to Yates being tapped by Steve McQueen for Bullitt the following year. The chase here is every bit as good, the film itself miles better.

In Justin Lin the Fast and the Furious series finally found a director capable of delivering the set-pieces it needed. The vault robbery that closes Fast Five is every bit as OTT as his cast’s line-delivery, his direction every bit as pneumatically muscular. Scale and excess are matched by a wit and spacial clarity missing from other franchise entries, its sense of escalation embracing the ridiculous with both seriousness and outright glee.

Even without the close-quarters smackdown at the centre of Gareth Evans’ ultra-violent road rage set-piece, the stunt work alone puts The Raid 2 in the top half of our list; his team as quick with a handbrake turn as with flurried fists. Par for the course, the scene’s in thrall to Evans’ bloodthirsty wit – that machine gun to the face! – but it’s his coverage of Iko Uwais’ battle with four goons in the backseat of the lead vehicle that seals the deal.

“It’s 106 miles to Chicago, we’ve got a full tank of gas, half a pac of cigarettes, it’s dark and we’re wearing sunglasses.” Like much else in the film, the extended chase at the end of The Blues Brothers serves up a smorgasbord of silliness and excess. A demolition derby of epic proportions that sees the police, the army, a country music group and a bunch of Nazis on the brothers’ tail. More than a hundred cars were wrecked at speeds of up to 120mph. Near untouchable for sheer frivolity of scale.

Okay, so technically another non-car chase… Buster Keaton hitches a ride on the front of a bike, speeding through ’20s Los Angeles. Not noticing the cop behind him has been knocked off, he careers through a series of near-misses. The escalation of obstacles in his path is magnificent, the timing of the sight-gags every bit the mark of a perfectionist. Stunningly executed, and not even the best sequence in the film.

For a director ever-willing to transpose his gobbiness to the screen, Death Proof provided Quentin Tarantino with his best opportunity to date to exercise his considerable action chops. His best or his worst film, depending who you ask (we’re in the former camp) there’s no escaping his unloading a lifetime’s appetite for genre fare into the film’s astonishing set-pieces. The climactic chase is as good as anything he’s done. Period.

William Friedkin made a pretty convincing bid to out-do himself 14 years after The French Connection. Much like his earlier triumph, it’s the attention and connection to character within the sequence that elevates it above so many of its peers. It also helps that it’s so magnificently constructed, climaxing with a headlong plummet into oncoming traffic. It’s one of the quintessential LA chases, making use of the city’s wide-open spaces almost as brilliantly as its predecessor did the claustrophobic intensity of the NY streets.

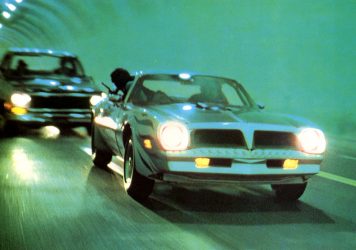

A decade earlier, in something resembling a transatlantic cultural-exchange programme, Jean-Pierre Melville imported Howard Hawks’ value-system for a series of cooler-than-thou genre distillations. With The Driver, director Walter Hill made a bid for repatriation, streamlining components to their merest essence. The result would prove hugely influential, not least on Heat and Drive. The stunt-driving is peerless (see the garage sequence); the opening and closing chases all-timers.

Forgoing the inessentials to craft a calling-card of sheer directorial prowess, a 25-year-old Steven Spielberg delivered a debut that was all about the chase. It’s an apprenticeship distilled, one of the great chase films, perhaps the greatest TV movie – Hitchcockian in both concept an execution. The ending roars, but perhaps it’s the railroad crossing sequence that demonstrates the wunderkind’s immediate mastery of montage.

When Howard Hawks suggested that William Friedkin “make a good chase, make one better than anyone’s done,” Friedkin duly obliged. The brilliance of the Brooklyn sequence, under the elevated railway, lies as much in Gene Hackman’s furious performance as the mechanics of the chase itself. Shot over five weeks, without all the necessary permits in place (some of the near-misses captured were unplanned), it’s a tour de force very few have bettered.

Roy Scheider may not have been involved in The French Connection’s celebrated chase, but he got a chance to go one better a couple of years later. The sole directing credit for the producer of both The French Connection and Bullitt, Scheider’s chase is one for the ages. A 10-minute pursuit through the streets of New York is thrillingly executed, but the best is saved for last – an out-of-nowhere gut-punch apparently modelled on Jayne Mansfield’s fatal crash.

The pedal-to-the-metal assault on Moscow at the end of The Bourne Supremacy shows Paul Greengrass’ much-imitated approach to action at its most persuasive. It also delivers on everything we want from a top-tier car chase, from extensive city-access to narrative stake-raising. Brilliant for its kinetic direction, stunt-driving, editing and photography (shout-out to series DoP Oliver Wood). The sequels couldn’t hope to top it. They didn’t.

As masterclasses in the chase go, you can really take your pick from those in Mad Max 2. It’s immediately clear that director George Miller understands, not just the value of practical effects – and of not cheating in the cut – but of his entire team, from stunt-player to editor. If we have to choose one, then the assault on the tanker is as good as any. And to think he’d go one better some two-and-a-half decades later…

There are countless sequences in James Cameron’s filmography one can turn to when looking for masterful action direction, but the viaduct chase sequence in T2 still takes some beating. Encompassing multiple elements and points of view, it’s a model of clarity and escalation. The below video essay by Shot by Shot’s Antonios Papantoniou offers an incredible breakdown of its constituent parts, demonstrating the complexity and precision of montage that allows it to seamlessly thrill in the moment.

The only filmmaker on our list to die in pursuit of the perfect car chase, HB Halicki served up one of the most expansive examples with a sequence lasting nearly 45 minutes. It was the sequel to Gone in 60 Seconds, 1982’s The Junkman, that took his life, but his 1974 effort stands as one of the greatest pursuits ever committed to celluloid. A car thief is tasked with stealing 48 vehicles, the last – a 1973 Mustang named Eleanor – being the one that sets everything in motion. As unadulterated rubber-burners go, it’s almost peerless. We’d put it at number one, but…

At once stripped back and deliriously overblown, the car chase finds its apotheosis in George Miller’s 2015 franchise jump-starter. A junkyard frankenstein of influences that seems to encompass and embody the entire history of the chase, shot through with a manic fuel-injection of Chuck Jones lunacy, Fury Road stacks its wit and invention with recklessly breakneck abandon. It’s the gold standard in auto-based action direction; selecting a single set-piece is a fool’s errand when all are so cohesively part of the whole. It doesn’t get any better than this.

What’s your all-time favourite car chase scene? Let us know @LWLies

Published 27 Jun 2017

Walter Hill’s cult film is full of intense car chases and silent antiheroes.

The director’s own professed black sheep is his most beautiful work.