“But I’ve reason to believe / We both will be received / In Graceland.” Paul Simon’s titular track from his 1986 album Graceland is a song about the American South and its glory days, about the redemptive power of its folk culture and, specifically, of its music. Jim Jarmusch’s 1989 film Mystery Train channels an equivalent spirit of belief through its tripartite narrative set in downtown Memphis after hours, where an assortment of characters drift in and out of flophouses and Dixie dive bars looking for some quiet salvation.

Featuring three distinct narratives each linked by Elvis Presley, a single gunshot, and a hostel fronted by a sinister, crimson-clad night clerk (Screamin’ Jaw Hawkins), Jarmusch’s muted, meditative film is a paean for the American landscape and its (often) lonesome wanderers. A Japanese couple comprised of the Elvis-adoring Mitusko and the stoic, Carl Perkins-imitator Jun feature in ‘Far from Yokohama’; a lone Italian traveller finds herself stranded in backwater Memphis overnight in ‘A Ghost’; and The Clash’s very own Joe Strummer, alongside Rick Aviles and Steve Buscemi, finds himself caught up in a liquor store robbery gone bad in ‘Lost in Space.’

Jarmusch’s ear for quickfire and naturalistic speech is the bedrock of his much-lauded style, and Mystery Train’s pared-down plot and shifting focalisers relies on his innate ability to give voice to the quotidian and mundane. People drink beer and smoke cigarettes (the latter of which Jarmusch dedicated to an entire film in 2003). They stare longingly out of dirty hostel windows. They eat, sleep, walk the deserted streets. Occasionally, a character will quip something that, in Jarmusch’s hermetically-sealed worlds of everyday speech, borders on the revelatory.

“This is America,” Jun remarks to Mitusko when staring out at the dreary Memphis twilight from their room. Self-reflexive, perhaps even a little meta-narratorial, those three words ground Jarmusch’s blue-collar study that is haunted by an undefinable absence.

The setting of the film is, as with everything else in Jarmusch’s repertoire, minimalist. Sagging clapboard homes and untended porches are the only indices of domestic space in the Tennessean sprawl, with the paint peeling from its movie theatres and the streets depopulated in the story’s backwater burg. “If you took away 60 per cent of the buildings in Yokohama it would look like this,” Jun notes when they arrive by train.

The majority of the film takes place across a single night and it’s here that Jarmusch’s Americana influences come to the fore: neon signs attract barflies like bug zappers; the sullen heat and the sound of crickets betray the wider South beyond Memphis. Mystery Train is a film about the American experience as it is perceived by the outsider – the drifter or tourist. The reality is sobering, stark, melancholy.

Mystery Train is also a nuanced commentary on excess and consumerism. Jun and Mitusko are archetypal tourists, with Mitusko insistent on guided tours of Sun Studios and, eventually, Graceland, despite hers and Jun’s inability to understand English. Graceland, as the films invisible locus, has in many ways transcended the music that birthed it and become instead a mecca of tourist-centric excess.

Similarly, Luisa is coerced early on in her time in Memphis to buy countless glossy magazines by a smooth-talking news vendor, and ends up giving them away unread to stranger-roommate Dee Dee (Elizabeth Bracco). Elsewhere, Johnny (Strummer) and his night of law-breaking stems simply from his desire to get drunk and buy two bottles of Butcher’s whisky, killing the store clerk along the way. Jarmusch seems intent on teasing out the excessive, gaudy allure of Graceland and other ports of cultural call in the South through his stories of outsiders and their reliance on money, both earning and spending it.

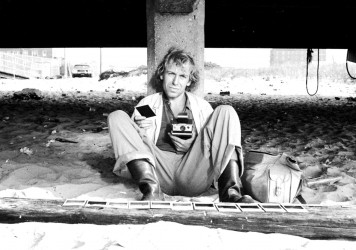

Mystery Train marks the convergence of Jarmusch’s most distinct and compelling traits as a filmmaker. His characters speak with an intimacy only achievable at night in a new town, or country, with a stranger in a hotel room. They experience the world around them in strictly sensory terms, denoted by the headphones-wearing, camera-wielding Jun and the haunting refrain of ‘Blue Moon’ that accompanies Louisa’s sighting of Elvis’s ghost. For such an unassuming stretch of downtown Memphis, Jarmusch’s film is alive with affect, both audible and visual.

Periodically throughout the film, the lonely knell of a train whistle sounds in the still, sultry night air. Trains become the leitmotif of Jarmusch’s south; people arrive by them and have their sleep disturbed by them. But their steady rhythm – their ubiquity – sets the film’s melodic pace. Mystery Train is a film about searching for experience and meaning in places foreign to us, alongside people stranger still. But in the endurance of that search, Jarmusch seems to suggest, is something noble, even heroic. As Elvis himself, the film’s star-spangled spectre, laments on the eponymous track: “Well that long black train got my baby and gone.” Just wait for the next one. It’s coming right a-round the bend.

Published 11 May 2019

By Zach Lewis

The indie idol discusses Paterson, the musicality of movies and how Man Ray made films for his band to play along to.

How Wim Wenders’ 1970s Road Movie Trilogy captured the romantic lure of American culture.

Director Jim Jarmusch found the perfect creative kindred spirit for his surreal monochrome western.