When Elvis Presley began his film career in 1956, he was at the peak of his popularity. Blending rhythm and blues and white male rage in the spirit of James Dean, the intensity of his on-stage performance oozed a primal sexual energy that helped usher in the 1960s. There was something dangerous in his shaking hips and upturned lip that made adults nervous. Like an unholy ghost, if you believed the fear-mongering, Presley would drum up riots, knife fights and premarital sex in any town he passed through. When he hit the big screen, the fear amplified as celluloid became the messenger force for his perceived vulgarity, reaching more young people than ever before.

In 1958 he released the third and arguably best film of his career, King Creole. Set in New Orleans, Presley plays 19-year-old Danny Fisher (a role originally intended for James Dean), who is struggling to graduate from high school when he accidentally stumbles into a singing career. Directed by Michael Curtiz and co-starring Walter Matthau, the film was primarily shot on location and is embroiled in the criminal underworld behind the cabaret scene of the French Quarter. It has an atmosphere of otherness, a pervading aura of the old world in a new land. Unlike his previous film, Jailhouse Rock, in which he plays a jerk, Danny is a sensitive, misunderstood young person pushed to the brink of despair due to circumstances.

Playing to one of the most prevalent tropes of the rebellious teen movies of the time, Danny’s father (Dean Jagger) is not a strong role model of masculinity. He’s a single parent who can’t hold down a job, so Danny and his sister work in order to keep an apartment for the family. His father firmly believes that an education will ensure a stable future for Danny, in spite of the fact that his own pharmaceutical degree has done little to get him guaranteed work. As much as Danny strives for his father’s approval, he also struggles to come to terms with his father’s passive nature, a source of major conflict within the film.

While Presley’s performance here is more nuanced than in many of his other films, it is still fundamentally an extension of the mythology built up around his musical career. When he sings, he comes alive and embodies the illusion of this sexed-up object of envy and desire. There are many artists from classic era Hollywood history who command that the medium bend to their talent and personality, and Presley is one of them. As Sheila O’Malley wrote in Film Comment last year, “‘Elvis movies’ are a genre in and of themselves. They share similarities with equally distinct cultural artifacts like Esther Williams’ swimming extravaganzas, or Busby Berkeley’s musical numbers. They create their own category and can’t be compared to anything else.”

Yet Presley’s film career showcased more than just a singer playing at acting; here was an authentic screen presence who was rarely given the material to test those boundaries. Working with Michael Curtiz was something of a boon to his ambitions, as the Hungarian director played to Presley’s strengths. Speaking about Curtiz, Presley’s co-star Walter Matthau once remarked: “He was a good teacher, but he never told you how to act, he just said, ‘You’re too loud, you’re too big.’”

There’s a kind of lethargic effortlessness, a sleepy way of glancing that makes Presley such a magnetic screen presence. He has a way of moving in slow motion, as though throwing his head back takes all the effort in the world. Whether he’s singing, kissing, dancing or thinking, every move he makes is deliberate. Everyone else jitters, he languishes, and like the consummate dancer he is, each action glides seamlessly into the next.

In one of the film’s stand out scenes, Frank picks up the five and dime girl, Nellie (Dolores Hart), for a date. When he speaks to her, he seems to eat her up as his glance shifts from her eyes to her chest. He reaches for her dress, adjusting something on her sweater. In this moment the explosive force of reality sneaks into the film, like a bomb waiting to go off. In the style of Marlene Dietrich toying with her feather boa in Shanghai Express, or Steve McQueen investigating his cowboy hat while Yul Brynner pontificates in The Magnificent Seven, Presley draws our unconscious eye to a real kind of engagement with the world.

When Danny finally makes his debut at the King Creole club, Curtiz masterfully sets the tone. The club seems small and sparsely populated. When Danny steps out onto stage, he is flanked by two pitiful palm trees from the previous banana strip act. As he begins to sing and gyrate, the crowd barely knows what to make of him. But the club seems to expand as Danny’s rhythm and sexuality cascade through the room. As he sings, Curtiz pulls the camera back to focus on a cocktail waitress passing in front of the bar. The King Creole, infused with smoke, full of shadows and sharp angles, is shot from every possible angle but Danny is the centre of that universe – a born star.

Presley’s film career is often remembered for his omnipresent candy-coloured musicals, but there is a special kind of dark magic at work in King Creole. If you believe the legends that Elvis Presley faked his own death in 1977, he would be turning 83 years old on 8 January, 2018. Of all his films, he considered King Creole his favourite and his best – and who are we to argue with the King?

Published 8 Jan 2018

Nick Pinkerton gauges the cultural impact of the clean-cut all-American icon.

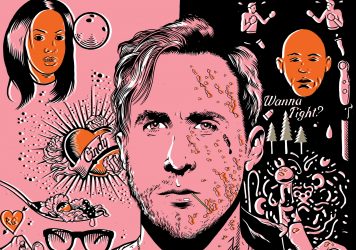

The Lost River director reflects on his childhood and ponders the myth of the American Dream.

By Elena Lazic

A lack of contextual depth and contrasting acting styles undermines this offbeat apolitical comedy.