By the time I turned 21, I had been to Fairmount, Indiana a half dozen times. Located a couple hours drive from my own hometown, Fairmount is the place where James Byron Dean grew up.

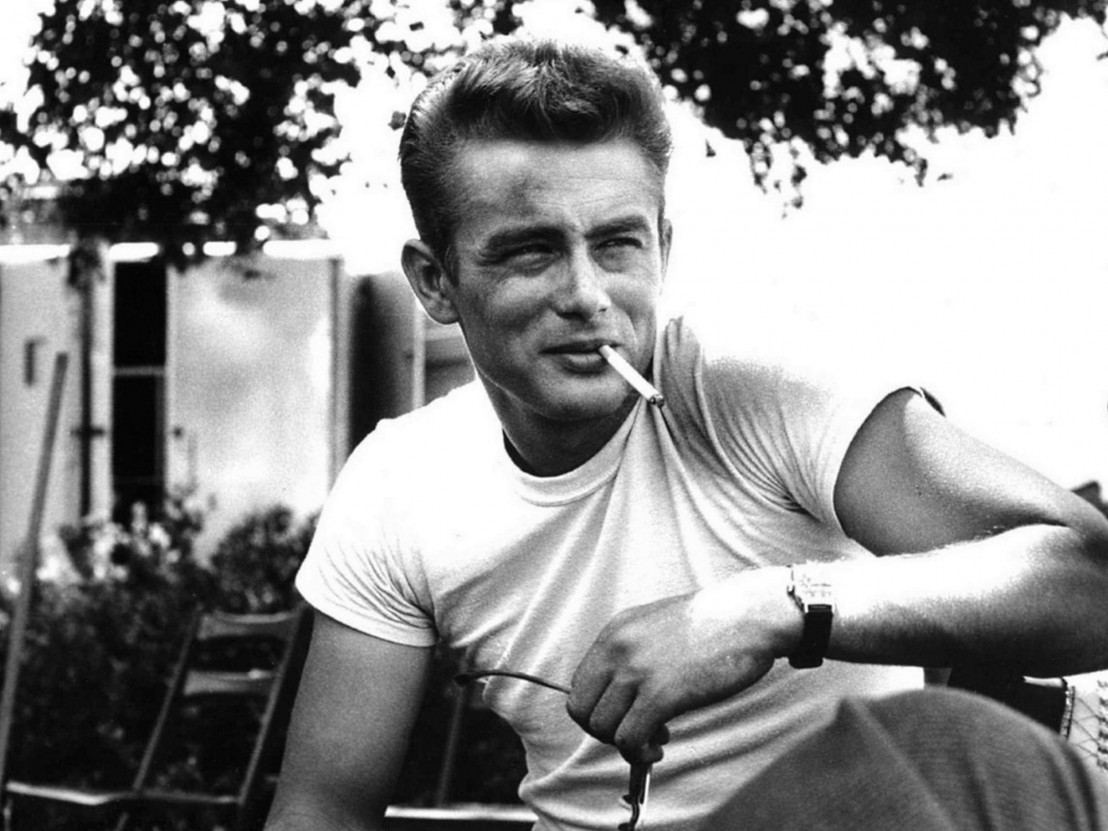

With a population of just 3000, there’s not much to see in Fairmount, certainly not enough to justify so many trips. On county highway 150 you can see the farm where Dean went to live with Ortense and Marcus Winslow, his aunt and uncle, after his mother died – it’s north of town, just past the Park Cemetery. In the winter of 1955, with Dean’s first movie, Elia Kazan’s East of Eden, poised to open that March, photographer Dennis Stock took a series of iconic portraits of Dean in Fairmount which would run in LIFE magazine. The pictures, in a spread subtitled “Barn to Broadway”, contrasted Dean’s bohemian life in New York City with his rural roots. In one picture, Dean poses in an open casket in the local funeral parlor. In another, he stands next to the headstone of one of his ancestors, Cal Dean – coincidentally “Cal” is the name of Dean’s character in East of Eden – in Park Cemetery, only a few paces from where he himself would be buried by the year’s end.

The framing of the Cal Dean photo is reproduced in the music video for ‘Suedehead’, the first solo single by Morrissey, who, before The Smiths, had written a paperback paean to his idol called ‘James Dean is Not Dead’. In the video, Moz swans about Fairmount and strikes various pensive and sorrowful poses against the sober Midwestern background, chugging around the Winslow farm on a tractor or walking the halls of Fairmount High School, the brick and limestone building from which Dean graduated in 1949, which has been boarded up since the ’80s. On one of my Fairmount visits, I hauled myself through the open second-storey window of the building, saw the dilapidated auditorium and the stage whose rotting boards Dean had once walked, and the same graffiti featured in the ‘Suedehead’ video, which reads “You Can’t Go Home Again”.

The phrase refers to a novel by Thomas Wolfe; Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause director Nicholas Ray would cadge it for an experimental film he made with his students at a state university in the ’70s. While he has fallen somewhat from favour today, in the 1930s Wolfe struck a chord with young men like Ray who felt estranged from the possibilities of the world they were offered. “Which of us has not remained forever prison-pent?” wrote Wolfe. “Which of us is not forever a stranger and alone? O waste of loss, in the hot mazes, lost, among bright stars on this most weary unbright cinder, lost! Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language, the lost lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door. Where? When? O lost, and by the wind grieved, ghost, come back again.”

James Dean unearthed what Wolfe called the buried life, spoke aloud of repressed, inchoate frustration. He got away with this, for a time at least, because he was a charismatic, ludicrously good-looking kid whose appeal worked on both women and men. Dean’s rise was roughly contemporaneous to Elvis’, except he never got fat. He played the lead in three high-profile films with A-list directors, and then died aged 24, while driving a very cool car very fast.

Before Hollywood, Dean had invented himself in New York. He took lessons at the Actors Studio and bought the beatnik identikit, bongos and all. Dean worked as a gigging TV actor – you can see him getting slugged by Ronald Reagan in a 1954 General Electric Theater telecast The Dark, Dark Hours on YouTube – but his reputation rests on those three performances. On three names, eight letters each, each one ending on a hard ‘k’: Cal Trask, Jim Stark, Jett Rink.

East of Eden was the only one of Dean’s films released before his death. It’s a custom starmaking vehicle – Dean is in practically every scene – and Kazan quickly establishes the template of the actor’s screen persona. Dean’s Cal Trask first appears sitting on a curbside, casting a surreptitious glance at a passing figure, the madame who’s rumoured to be his absentee mother. Following her, he hangs back at a distance. He is outside, apart, alone. The kids at school, we learn, have nicknamed Cal “The Lurker”.

East of Eden was the first Dean film I ever saw. The image of Cal alone riding atop a freight train boxcar, shivering and huddled, punctured me. Deprived of love by a preachy, withholding father who dotes on his brother, Cal is always grasping for something to hold, clutching himself when there’s nothing else. Juvie toughs for decades to come will imitate bantam cock Dean’s trick of puffing up his biceps by folding his hands underneath them. Dean is full of such expressive resources; elsewhere he winds his hands through the straps of his overalls, as though his arm is in a sling. The effect here underscores Cal’s wounded vulnerability, while some of Dean’s more baroque mannerisms are simply bizarre: after a punch-up with his brother, Cal stumble-runs to the nearest saloon and, ordering a slug of whiskey at the bar, proceeds to fumble the glass as though he’s never held one before.

If East of Eden established the Dean persona, Rebel Without a Cause, released a month after the actor’s death, emblazoned it in legend. Dean plays a California teen in both films, but Eden is set in the years before and during the Great War, while Rebel takes place in an entirely contemporary suburban Los Angeles. Dean is still fending off the cold as Rebel opens, drunkenly tucking a discarded wind-up toy monkey under a piece of newspaper, proof of Jim Stark’s nurturing instinct. This is, however, a paltry shelter against impending Armageddon. Rebel is structured as a chain reaction of explosions leading towards a Big Bang: the backfire of the scooter driven by Plato (Sal Mineo) that announces the raising of the American flag over Dawson High School; the drily-narrated end of the universe in the Griffith Observatory planetarium; the “chickie run” that ends in a fatal plume of fire – the film’s original treatment even had Plato committing suicide with a live grenade!

Rebel blew a hole in the public consciousness, widened the breach through which pop culture as we now know it would spill. In 1955 Dean was labelled the latest emissary of The Method, of a private, inwardly-generated acting style widely associated with Brando’s mumbling. Dean, who idolised Brando, would often deliver his lines like secrets, turned away from whomever he’s addressing. But what strikes the contemporary viewer about Dean is his swashbuckling brio, the way he bounds, sneaks, climbs, skitters. He has all the quicksilver mutability of youth – of picking up identities, trying them on for size, and discarding them, one minute boisterous and expansive, the next aloof and crabbed.

Looking at Eden and Rebel alone, we can find some justice to Thom Andersen’s statement in his film essay Los Angeles Plays Itself that Dean was “more of a rebel in life than in the movies where he always played a milquetoast Oedipus, trying not to murder but to please an imperfect father who is either too stern or too soft.” This formulation is complicated by Giant, however, and by Dean’s Jett Rink, who has no father to suck up to.

George Stevens’ film is a hulking adaptation of Edna Ferber’s novel of the same name, about a Texas family, the Benedicts, and its ancillary members. The protagonist and patriarch is cattle baron “Bick” Benedict (Rock Hudson). Bick is big, straight-backed, forthright, with all the confidence of century-old landed gentry in good standing. Dean’s slinky Jett Rink is a blight on Bick’s kingdom, wily wildcatting white trash scratching around on the lean ends of the Benedict property for oil. Pushing his Stetson down over his expressive steepled eyebrows, Dean uses the shadow cast by its brim as a hiding place. He’s playing “The Lurker” again: at a communal barbecue, where Jett warily views the proceedings from behind a horse’s flank before slipping into the back seat of his boss’ enormous roadster and putting his feet up, imagining what it would be like to give orders. Like all of Dean’s characters, Jett has the feeling that he has been born in the wrong place. “Me,” he says, “I’m gonna get out of here one of these days.”

We get to see what becomes of Jett’s ambition. He strikes oil, and the movie leaps forward 25 years. The shy young peckerwood with a casual dependency on alcohol has become a middle-aged plutocrat and catastrophic toper, further retreating from the world behind sunglasses, a cloud of bourbon and a pile of money. Dean would always bobble lines, but his grey-templed Jett is barely verbal. While most actors playing drunk feel the need to let their intelligence shine through, here is one of cinema’s most no-quarter, fall-down-knee-walking-blackout-squiffed performances. This Jett Rink is the sum of Cal or Jim’s fears for their future: A stunted, bitter brat who never learned how to grow up.

No less than the sententious patriarch of East of Eden, Stevens favours his good son. Bick learns humility and finds grace; Jett learns pride and is cast into perdition. Jett embodies the worst barbaric excesses of the Texas nouveau riche, like Paul Newman’s title character in 1963’s Hud. But Jett’s arriviste fecklessness, like Hud’s, is more magnetic than the plainspoken decency to which it is contrasted. I suppose there must be people who watch Giant and are more interested in the Benedicts than they are in Jett Rink, but I can’t claim to understand those people. The movie is electric, jaggedly modern and alive when Dean is on-screen. He’s a hot-rodder who pulls into Stevens’ elegiac prestige picture only to do doughnuts all over it.

We all know what happened next. Dean’s follow-up to Giant was to have been 1956’s Somebody Up There Likes Me, but the role of Rocky Graziano went to Newman instead, the actor’s first film lead. Newman was compactly built with a dashing close-up ready bust – and he loved cool cars, too – but nobody could just waltz into that Dean-sized hole. Dennis Hopper, who’d appeared with Dean in both Rebel and Giant, knew he wasn’t up to the task, and instead proselytised for the personal cult he created around his late friend.

Dean’s wreck was a big mess, and we’re still finding little bits of Jimmy everywhere: in Hopper’s countercultural ideal and Charles Starkweather and The 400 Blows and James Deen and, yes, in Morrissey and his “It takes strength to be gentle and kind.” The ambiguous masculine identity that Dean projected is distinctly American, and paradoxically this makes him easy to translate. Wherever the piteous cry “O lost” goes up, that’s where he can be found.

This article was originally published in LWLies 52: The Muppets Most Wanted issue.

Published 22 Sep 2015

With Snoopy and Charlie Brown back in cinemas, Nick Pinkerton explores the legacy of Charles M Schultz and other innovative cartoonists.

Is it possible for women to love movies which promote a regressive, misogynistic worldview?

By Liam Dunn

From Shock Corridor to White Dog, the late director’s work has lost none of its social relevancy.